When Chimodu* (28) joined a music label in the 2010s, he thought it’d help him get his big break. It didn’t. He shares his experience navigating contract issues at the label, developing a cannabis addiction and having to go to rehab, and how he’s slowly piecing his life back together.

For anonymity, names and other identifiers have been changed.

This is Chimodu’s* story, as told to Akintomide

I was trying to adjust to the reality of life after uni when my friend, Ogbe* convinced me to apply to a Nigerian music label’s academy.

I’ve been into music since I was a teenager, and he thought the academy would help me better my craft. It made sense, so I applied.

The label’s head is a well-known Nigerian artist and, up to that point, had been one of my biggest influences as a producer. It was an opportunity to learn from my idol, and I knew I had to take it. I even told some of my guys I’d get in even before the academy picked me. I wanted it that much.

Getting selected was the validation I needed at the time. Up till then, everything I knew about music was self-taught. But being something of a nerd who wanted to understand things from every possible angle, I knew I needed more technical knowledge. The academy provided that; a chance to ask questions and hone my skills — a stepping stone.

Little did I know that this “stepping stone” would turn out to be the feet-hurting pebbles that’d steer me into a path I least expected to take.

I resumed at the music academy in 2013 for the month-long training. The first day was nerve-wracking, at least for me. I met the organisers and the other students, and we started talking about ideas and techniques immediately. I noted something odd, though. Anytime I asked a question about music production or other technical stuff, the label head would say, “Just choose better sounds”.

Besides the odd attitude to questions, it was a comprehensive training. They taught us about the music business and branding. Top producers, songwriters and industry people came to talk to us. There was even an entertainment law class, where we were taught not to work with anyone without signing a split sheet that detailed how payment would work.

But a week into the programme, the organisers began to emphasise how we needed to “do anything it takes to succeed in the game”. They asked if we’d give them the intellectual property (IP) rights to the music we’d make while in the academy. The music in question was supposed to be an academy project which seemed to be a requirement for the training, so we all said yes.

I should mention that the whole training was filmed, so they had video evidence of each student agreeing to release all IP rights. It wasn’t a red flag at the time because, in my head, the academy would be my big break. Even if they owned my music, the exposure would do me a world of good.

The project never happened, by the way.

Fast forward to the end of the training. The organisers gave us all a one-year contract to become official signees of the music company. There was a clause, though: They’d also own everything we produced under the label.

I showed my dad the contract, who in turn showed it to his lawyer best friend. The lawyer asked me not to sign it. I was pained, but I had to tell the label lawyers I couldn’t sign based on those terms. They refused to negotiate and asked me to remove all brand benefits like academy logo, social media handles and hashtag in the bio from my social media accounts. I was even subtly threatened not to “misyarn about them” or I’d be sued for causing “emotional distress”. It felt like I was stripped of an honour and taken back to square one.

I couldn’t release music immediately after the academy because I thought they’d accuse me of using the social media leverage that attending the academy had given me. I didn’t want anything to tarnish my reputation or end my career before it even started, so I stayed off social media.

While this was going on, a former mate at the label started making waves. All the hit songs on the radio had his name, and I started overthinking about money and blowing up, too. I even briefly considered contacting other guys who also attended the training, but thought against it. The lawyers would probably have told them not to talk to me or each other.

So, I kept to myself. Then one day, Ogbe* told me that the lawyers from the label were trying to reach me. They’d told Ogbe* what happened and claimed I didn’t honour an agreement. One even said she was looking for me because she was worried.

I thought, “Oh, maybe things can be ironed out.” So, I called the lawyer and said I was hoping to negotiate the contract. She called me a dumb ass who had wasted an opportunity and that I needed to apologise to the lead organiser for wasting his time.

It was like a switch flipped on in my head. I knew I wouldn’t receive that treatment if I had a hit song, or if I’d “blown”. That was my “fuck it, I must make money” moment.

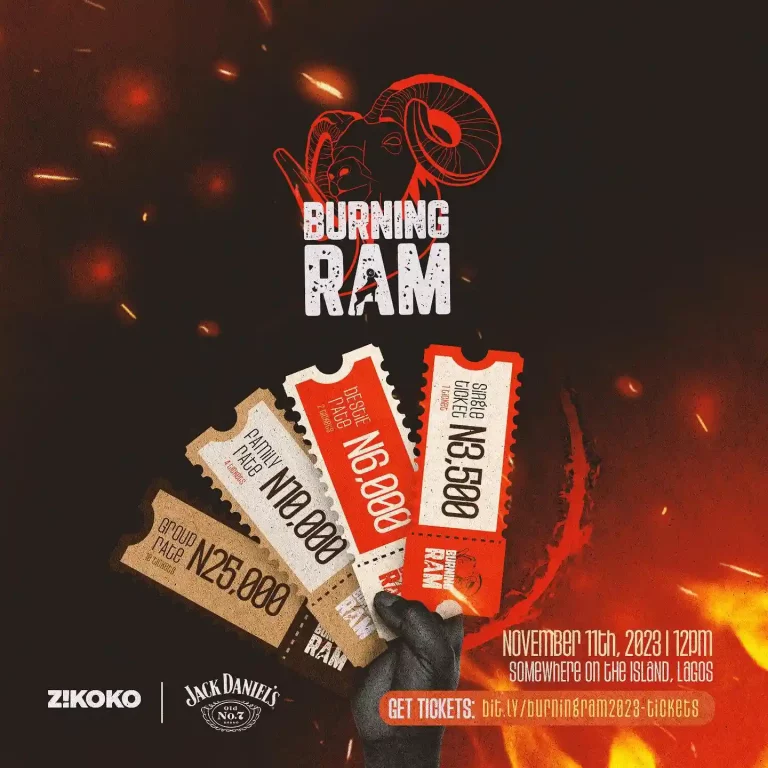

Yoo! Our Burning Ram Meat Festival will be live on November 11th. Come celebrate with us the Naija culture of meat and grill. See you.

Click HERE to buy a ticket.

The only problem was, I didn’t know how to invest in myself to make the money. It took me four years after the label to put out music again, and when I resumed, I focused all my energy on it, believing I had a talent people would pay for. I didn’t have a job, or money to get equipment like a studio monitor, better microphone, software, things that would help me level up.

I just expected at least one of my songs to blow up because I put out music with friends every three months and I produced songs regularly for others.

I was a studio rat, but I didn’t have a direction for myself. It was only fun and pleasure. I spent all my NYSC allawee on babes and weed. Same thing after my Service and during the three years that I worked as an accountant at a private firm.

It wasn’t until I lost three years in rehab (due to my cannabis addiction since my uni days), just wasting away, that I started to take my life seriously. When I came out, two of my guys had gotten married. A couple of others had changed their cars. Guys were making moves. That was when I said, “Omo, I’m done sitting on my ass.”

I saved up and bought a MIDI controller. I had a guitar I’d never played. I’m now learning how to play. Then, I went to a software engineering boot camp. I’m working towards positioning myself for a steady income stream from my various passions, from music to game software development to drawing and making short films.

Currently, I’m a games software developer, and I run music projects on the side. After the projects I’m working on come out, hopefully this year, free work stops.

Another thing driving me to hustle now is to look at luxury cars on IG. Benzos, Lexes, Bentleys.

But all in all, I need to make these things work, even for another reason, like my parents. They’ve done their best. But also, I need to get out of their faces. My dad thinks I’m wasting time with music and my mum treats me like a child. I don’t want all that for my life.

My music career hasn’t turned out the way I expected, but I’ve accepted that this is my journey. I’m glad I didn’t sign into that label. Every other person in my set signed, but most are still on the same level as me. But I’m not going to be here for long, it’s grinding season for me.