There is nothing Nigerians haven’t tried in order to gain the government’s attention on just how — for lack of a better word — displeased, we are with their leadership.

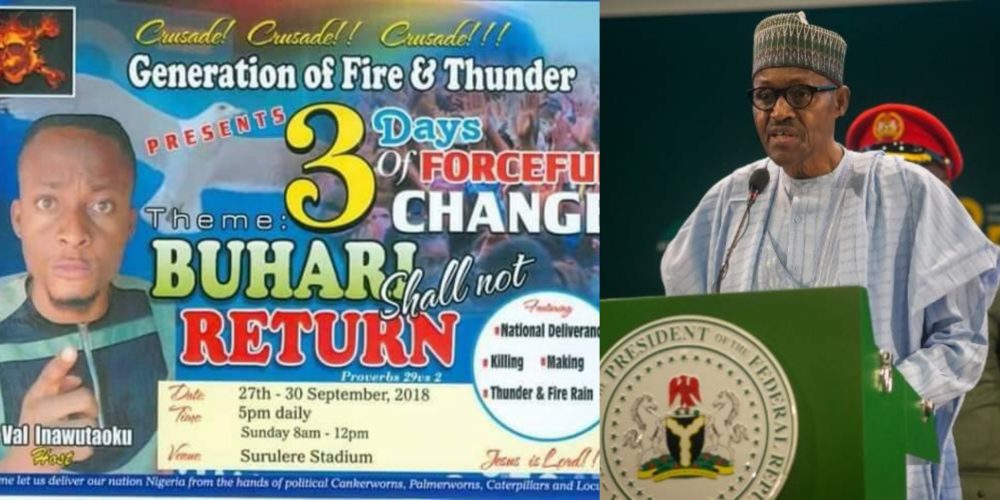

We’ve held church crusades.

We tried nationwide strikes.

We’ve attempted and succeeded at coups. We’ve held protests and tested the occasional name-calling. But nothing, nothing at all looks like it’s going to get the government to pay university workers their due, disburse a livable minimum wage, fix up the health sector, repair all the terrible roads and get children off the streets and into schools etc., etc., anytime soon.

With these trial and error methods gone out of the way, it might be time for Nigerians to look in another direction; it might be time for us to try “The Mali Approach”.

Now you might wonder, what is the ‘Mali Approach’? To explain, let’s examine the country’s state capital, Bamako.

Bamako, Mali.

Mali has a largely agricultural economy — 70% of its workforce engage in the trade. The most productive agricultural areas of the country lay along the Niger River, which is between Bamako and Mopti. The north of Bamako is home to the largest concentration of cattle in the country.

Bamako is also the nerve centre of Mali; local and international trading in the country’s agricultural produce, livestock and fish take place here. It is a major link to a principal port of trade with Dakar. What this means is that Bamako is quite integral to the existence of Mali. It is so important that, without the state capital, Mali would lose about 36% of its GDP.

That’s why what you’re about to read is shocking: You know what a group of people in Mali did to the roads leading up to Bamako in August 2019?

They blocked it.

Now, why would they do a thing like that?

Two words: bad roads.

Mali is a country plagued with close to impassable roads. Multiple directives on the internet warn travellers and visitors to be careful of its roadways. Having had enough of the government’s nonchalance to fixing the roads, a group called Sirako (which translates to “about the roads” in the country’s Bambara language), joined residents in blocking the main way leading up to the country’s capital. This blockade went on for about four days, gravely disrupting trading activities in the country.

The blockades.

The blockades started on August 23 in the western city of Kayes. Hundreds of residents blocked the main bridge over the Senegal River.

By day four, the protests had spread to other regions: over 1000 trucks loaded with merchandise for trade were stuck outside of the city’s capital – Bamako.

Attempts by the government to have the blockades removed proved abortive — the Prime Minister couldn’t get representatives of the people to budge.

Within the time the blockades stood, dealers in fruit feared for their produce, which were stuck in trucks unable to access the city capital. Bus passengers had to walk kilometres to make it into Bamako.

The country was in a standstill, because a few citizens decided, enough was enough.

The aftermath of the blockades.

By August 28th, less than a week after the blockades started, the government released an ’emergency’ 5.0 billion CFA francs, for the resumption of a major highway project to fix the roads leading up to the city capital.

See where a little strong head can get you?

Now, this might not work in the Nigerian context because well, you don’t need to do much before tear gas makes an appearance during protests. But, it does make you think. Hitting the government where it hurts just might be the way to go.