Every week, Zikoko seeks to understand how people move the Naira in and out of their lives. Some stories will be struggle-ish, others will be bougie. All the time, it’ll be revealing.

Luno is a great way to get into cryptocurrency Download and start trading today.

The 29-year-old subject of today’s #NairaLife is an Ifa priest born to Deeper Life parents. After a series of unfortunate events hit his family in 2001, he found solace in Ifa’s temple. Today he lives and earns money as a babalawo, and his finances? Divinely secure.

What is your earliest memory of money?

The first time I had money of my own to spend, I was 10, and my parents had just separated. My mother was sick in the hospital, and I was living with some family friends because we had also lost our house.

People aware of our situation would see us and give us money along with their condolences.

I’m so sorry. Why was this the first time you had money though?

My parents never allowed us to take anything from anybody. We were a Deeper Life household, and they were very particular about who my brothers and I hung around. We were practically cut off from our extended family, so there were no uncles and aunties to give us money.

But even when we did get cash gifts, they came from parents and teachers at the school my mother ran. These gifts were never really for us to do what we wanted. My mother had complete control over them.

How much would you usually get?

₦50 and ₦20 there. Nothing too crazy. But it would add up over time, and after some time, I’d have saved up to ₦700 or ₦1000, which was a lot of money for the late 90s / early 2000s.

I agree. So what did you spend this money on?

Books.

Lol, why?

Books were always a part of my life. My mother was a mathematics teacher and the proprietress of a school. We had food, shelter and everything else we needed, so when there was extra money, my mother put it towards getting more books.

If you didn’t have to spend that money on books, what would you have done?

There was this bicycle you could rent and ride in the neighbourhood. I didn’t have a bicycle, so I’d have wanted to spend my money on that.

But I don’t have regrets. Reading those books helped open my mind. They’re one of the reasons I’m an Ifa priest today.

Please explain.

The first thing books did was make me question everything.

I was 8 when I read The Destruction of Black Civilization by Chancellor Williams. It made me see the beauty that Africa had before colonisation. That was the beginning of my journey to being a non-conformist.

I came across Ifa later in a recommended book in secondary school. The title was “Awọn Oju Odu Mẹrindiogun” written by Prof. Wande Abimbola. Ironically, this was a book I found in the library at my mother’s school. If only she knew.

The book was written entirely in Yoruba, and when I got to the part of the book that spoke about Ifa and traditional worship, the prayers I saw there read like poetry. They were prayers I believed anyone would want to say for themselves. I was expecting to find occultic evil incantations like in Nollywood movies.

Interesting. When would you say you finally went beyond the books?

I couldn’t do much because soon after my family went through a rough period.

What happened?

It was a series of unfortunate events that started with a tortoise car my mother bought for my father.

In 2001, my father lost his job at Guinness. Of the two of them, my mother was always the wealthier parent, and she wanted to get a car for herself. She changed her mind for two reasons: she couldn’t drive yet, and she thought my father would get more use out of it.

His family told him my mother was trying to steal his destiny by giving him the car. He was advised to cut her off and leave us alone. That’s precisely what he did. He never drove the car, and it stayed where it was till it rusted.

There’s a lot to unpack here. But first, why didn’t she continue using the car?

While he was leaving, other things were happening. Our house and my mother’s school were in Meiran, and the school was doing well for a while. But in this same year, we got eviction notices from the landlord of our home and of my mother’s school.

At once?

It wasn’t funny o. As if that wasn’t enough, she fell sick. It started as something small, and when she was admitted, the doctor told us it would be for about a week. That turned to seven months. It was while she was in the hospital and dealing with all the quit notices that she gave birth to my fourth brother prematurely.

Where were you at this time?

I was still home, and I was going to my mother’s school, but things weren’t looking good. People had heard about the place being closed down, and my mother was in the hospital. Parents started to withdraw their children, and without children to teach, the teachers left as well.

I moved in with a family friend and lived with them until my mother was out of the hospital. When she was better, she went to a property she had at Ijaye in Lagos. She was building a school complex there before all these bad things started. She discovered that the land she had been building on apparently belonged to someone else. She had been duped.

My mother cried a lot during this time. She kept going to the Oba of Ijaye with my newborn brother in her arms. She did this until they gave her some land in Sango Ota, so that she would stop coming there to cry. We eventually moved into a small bungalow she constructed on that land. My brothers and I joined her later.

Oh wow.

It felt like fate when I met my first babalawo in Sango-Ota. He was our neighbour, and he’d often send us food during any celebration, but my mother ensured we never tasted any of it.

At the time, I knew there was nothing to be afraid of. I’d read more books about Ifa and knew that all the stereotypes attached to Ifa worship were a lie. But I was not going to use my mouth to say that to my mother.

My new school was around Alakoko and just happened to be beside one of the biggest Ifa temples in the country. That was where I first started studying Ifa under experienced babalawos. I was intrigued by the fact that the temple owner had a doctorate. It was refreshing to come into the temple and hear bright young men consulting each other, saying prayers and helping people find answers to questions about their lives and destinies.

Till I left secondary school at 14, the temple became the one place I could go where the world was not burning around me. Being around Ifa gave me peace.

You were 14 when you finished secondary school?

Yup! I skipped a few grades in primary school. I was quite gifted in a lot of my subjects.

How were things at home during this time?

At this point, my mother was trying to get back on her feet. I still got money from friends and family who came around or saw me at school, and my mother would give me money often. She didn’t object to the money I was receiving because she didn’t feel like she could chastise us anymore after what had happened. I averaged about ₦2,500 monthly by the time I was leaving secondary school.

So university came next?

Not exactly. It took a while before I got into uni.

How come?

I can’t explain, but I’ll try.

My friends and I started a free tuition class to help ourselves and others pass the entrance exams. After the tutorials, we took the exams, but I was the only one who didn’t pass. I didn’t pass WAEC, JAMB and NECO for three years.

At home, things weren’t funny. I was dealing with pressure from my parents to go and work in some of the factories in the area.

“Parents”?

Yes, my father came back after four years.

Sir?

There wasn’t any pomp or pageantry. He was gone for four years, and we didn’t hear anything from him. All of a sudden he was back and was our father again.

Okay. Please proceed.

These factories paid about ₦500 a day, and my entire spirit screamed no. I decided, instead, to make the tutorial a money-making venture. We were recording impressive success rates — just not for me for some reason.

In my second year at home, I partnered up with my mother and made the tutorials even more legit. For subjects I didn’t know too well, she brought teachers to help.

On average I was making about ₦10 to ₦15k monthly from the tutorials.

Eventually, I got into Yabatech to study electrical engineering in 2012.

Thank Ifa.

Thank Ifa because it was the year I decided to sacrifice something to Ifa that I passed JAMB. I couldn’t afford to get a goat or anything by myself, but I bought agidi (eko) and used it. With Ifa, you’re always told to do what you can.

But I saw shege in Yabatech o.

Ah, what happened?

A few months into school, I had a massive fight with my parents about studying Ifa, which escalated. I was disowned, and my siblings were asked not to speak to or collect anything from me.

How did your parents find out?

Before I started charging for the tutorials, my mother had a dream. She saw me wearing white clothes and holding a lion cub. She interpreted this dream to mean I was probably desperate for money and willing to do rituals. It’s interesting to note here that a lion cub is a symbol of Ifa.

That dream caused some friction, but my mother figured the tutorials would help with money, so she was willing to help me there.

When I got into university, I started going to the temple more often and being part of divinations and generally enjoying my time with Ifa. Some family friends came to the temple for some divinations and saw me.

They reported to my mother.

I was taken to several deliverances where pastors prayed and fasted to get the “demon” out of me.

I can’t even imagine how horrible that was. How were you surviving in uni?

Wo, survival is relative. I was barely getting by, but I had to fend for myself. Since I couldn’t collect Jesus’ money from my parents, I did everything I could.

I worked in the school cafeteria for a while, sold past questions, did night tutorials and even wrote exams for people. For a full day of these things, I was making about ₦3k or ₦4k.

I couldn’t get this every day, but I was making enough to eat and not die.

When did things change?

Around 2014, two years in, I went to visit a young lady I liked at the time in her departmental building. When we were done talking, I heard a lot of intense arguing coming from a room. I peeped in and saw members of the student government. I waited outside for a few hours because the way they were talking sparked something in me, and I wanted a chance to be like that — someone who could speak truth to power.

I spoke to members of the parliament at the time and decided to run for office. While I did this, I was also writing and editing as the editor-in-chief of a publication on campus. That wasn’t a gig that paid.

Being in parliament changed things for me. I didn’t have to worry about the ₦14,500 per semester hostel fees anymore. We were also paid a salary and sitting allowances for every meeting.

What did those add up to?

I know the sitting allowance was ₦1500. It was cemented in our heads because we were always looking forward to the payment that followed those meetings.

The salary was about ₦30k per semester.

Enjoyment. So by 2015, you were done with school?

Not exactly.

Hm?

Unfortunately, I was told that I could not graduate.

Sometime in 2015, because I wanted to use my voice and position as a member of parliament, I wrote a petition against five lecturers in my department. They were notorious for refusing to teach students if we didn’t pay some extra money. Nothing about it made sense. They would collect money for frivolous reasons and make life harder for students.

It didn’t sit well with me. I love all these freedom fighter things. And in all of it, my thinking was, “If this has to get messy, Ifa is around.”

It got messy, but I think the part that shocked me the most was having my fellow students chastise me for coming out to complicate things for them.

I ended up just leaving without my certificate. Sometime in 2020, Yabatech announced a programme that allowed people like me to get their certificates. That was how I was able to get mine and sign up for the BSc programme I’m doing now.

What did you do after leaving Yabatech?

I applied and got a job at an oil company. It was an entry-level role in the brand and communications department, and it paid ₦120k a month.

Things were better. After I was disowned, I swore never to return to my mother’s house and stood by it. My siblings started to reach out more because they needed things, and of course, I sent money.

During the holidays, I went to my new home — Ifa’s temple. There is an unwritten rule with the temples: if a person shows up and says they want to learn about Ifa, they automatically have a place to stay and food to eat.

I visited so many temples, around Lagos and even beyond. I would spend my holidays in the place I felt happiest while learning about something I truly believed in.

Did you feel any guilt about practising Ifa given all that was happening with your parents?

No. My conviction was too firm. I knew what I was doing wasn’t wrong.

How long did you spend at the oil company?

A year and four months. Before I eventually got fired.

What happened?

Looking at my life, you can tell that I’m someone who will always try to challenge the status quo. I’m not normal.

There were probably other reasons for my eventual sack, but one event started everything.

After a long fire drill that caused everyone to miss lunch, we all packed into the company cafeteria to get food. We stood in line like civilised people, and then all of a sudden, these Indonesian guys walked in and tried to get into the space ahead of us. I said, “For where?”

I screamed the house down and told everyone willing to hear that it wasn’t right for them to get special treatment just because of their skin.

This got me a warning, and after another incident, I got moved to the Apapa office.

I went from working on content for the brand in the head office to directing trucks and liaising with the tanker drivers.

Ouch…

Don’t ouch o. It turned out to be a blessing in disguise.

At Apapa, they called me Solution. For any process that needed to be sped up or even created, I was the guy to talk to. So on some very good days, I could pocket about ₦30k.

I eventually had to leave the company. I don’t think they ever really saw me the same after that first incident. Once there were signs that they would try to fire me, I accepted what was coming and left. I had about ₦450k in my savings, but that finished in four months.

What finished it?

There was black tax. But I was also living like someone that was expecting to get a new job quickly.

I did get a job eventually, but it was far from quick and an awful experience. I was the social media manager for a local newspaper. I was getting paid ₦8k a month.

Eight thousand naira?

And the owner stopped paying after three months. He travelled and sent everyone else’s salaries except mine. When I asked him, he said he was not seeing the effects of my work. For a brand that had no social media presence before I joined, he was asking for too much.

After I left this job, I was feeling tired of life, and while everything crossed my mind — even fraud — I just knew I didn’t want to compromise on certain things.

I returned to one of the many Ifa temples I’d visited over the years. I spent a year studying and living in the temple.

Is this when you became a babalawo?

No. I studied because I wanted to know more about Ifa and the orisas. The temple was still the only place that calmed me and made me feel better.

Becoming a babalawo came later. After my year of study at the temple, I decided to join a political party and possibly forge a political career. I was trying to do everything except become a priest even after I’d been told by different people in the temple that this was likely my path.

Where did politics take you?

Abuja. That was another horrible ordeal. I wasn’t getting paid by the political party even though I was working. I squatted with a friend of mine, and once, I was stuck in the house with the dog for three weeks. I had nothing to eat and had to call different people to get money. I eventually sent a message to one of my siblings asking for some urgent ₦2k. He sent me a long text that hurt me. It wasn’t something I expected from someone who I’d helped with money almost his entire life.

I decided that day after taking a long look at my life. If Ifa was calling me and the temple gave me peace, why was I running? I’d already studied and knew enough to be a babalawo, but I wasn’t convinced I could earn a living just as a babalawo.

How do you make money now that you’re one?

I do divinations and perform rituals that are needed for people, and they pay for the consultations.

Over time, I’ve gotten a fair bit of publicity for the work I do, and this has increased the number of people I see and do divinations for.

On average how many people do you see in a month?

For a while, I was getting up to 200 requests daily after a period I went viral. That number has dramatically reduced, but I’d say I still see about 100 people a month.

How much will divination cost me right now?

Honestly, there’s no set amount for these things. It depends on what the situation is. Money comes in trickles. ₦10k here, ₦50k there. One month, I received up to ₦2 million. Sometimes I do it for free. But always, almost immediately, something takes it.

Something like what?

I currently have about six people living with my wife and me, so on one hand feeding is taking a chunk of my money as it is.

What’s something you want but can’t afford right now?

I want to set up a radio station focusing strictly on African spirituality. I want people to see our local religions for the belief systems that they are and not what Nollywood has plied people with.

In the meantime, I’m doing the work I can with my podcast.

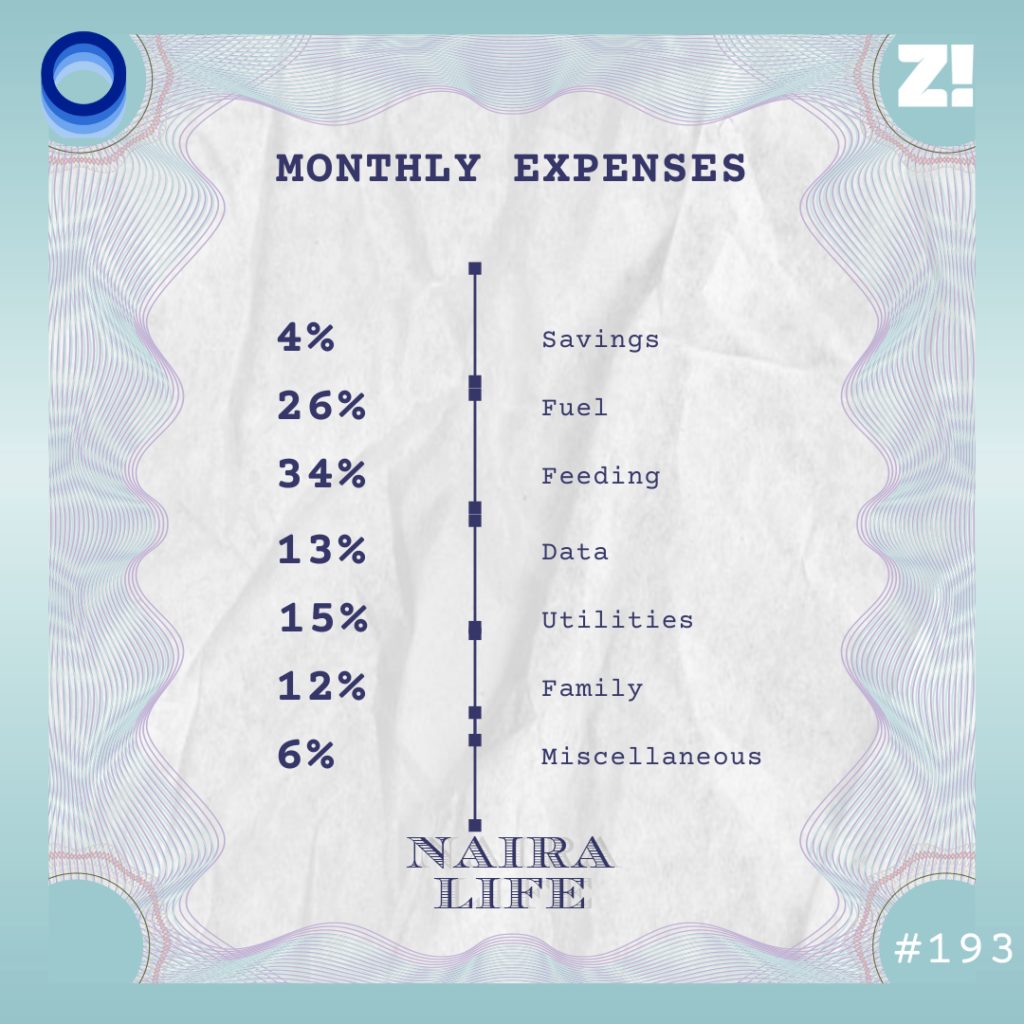

Your monthly expenses?

How would you rate your financial happiness from 1 to 10?

6. From the moment I decided I wanted to be a babalawo, I’ve never been financially stranded. Now, things just happen for me, and I get money from places that genuinely surprise me.

Luno is a great way to get into cryptocurrency Download and start trading today.