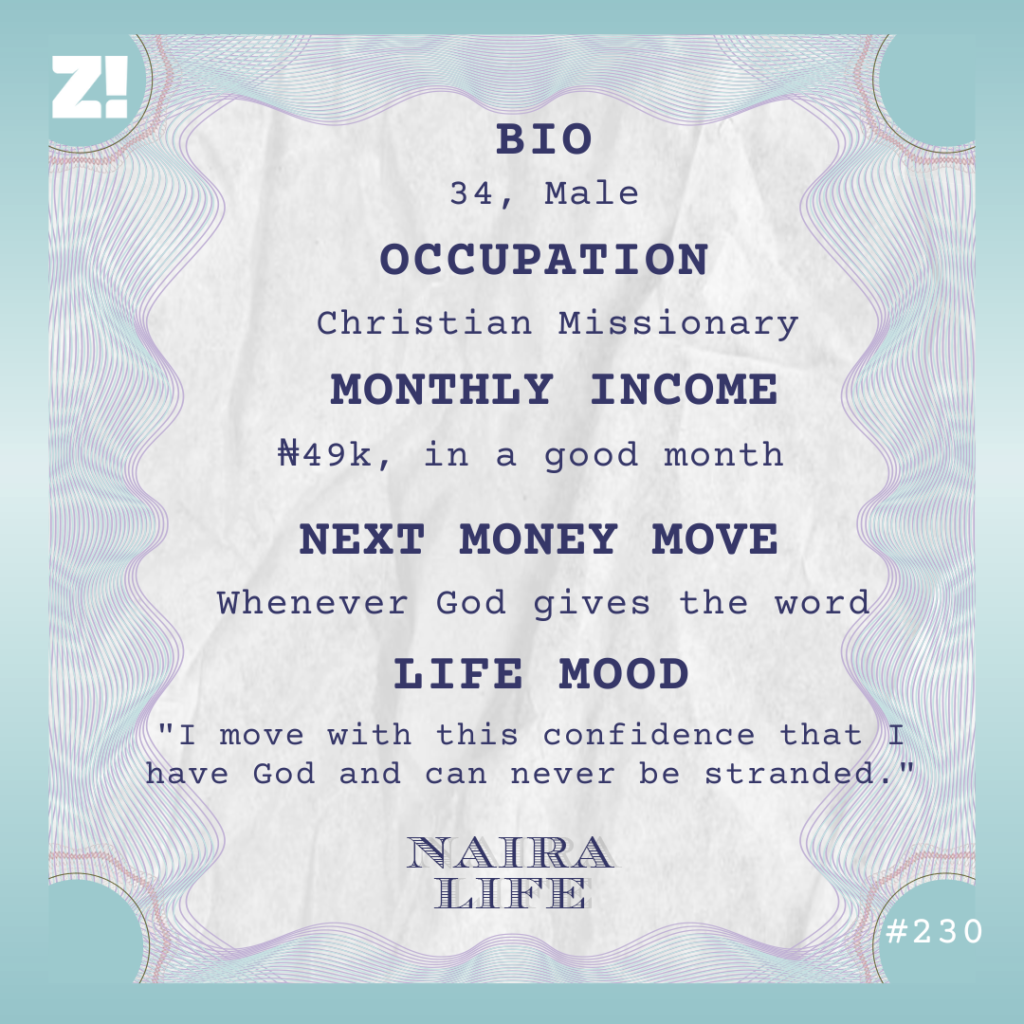

Every week, Zikoko seeks to understand how people move the Naira in and out of their lives. Some stories will be struggle-ish, others will be bougie. All the time, it’ll be revealing.

What’s your earliest memory of money?

My mother paid me my first-ever salary. When I was in Primary Four, I started going to her tailoring shop every day after school with my elder brother. Our job was to handle the weaving machine. After she was done sewing a piece of cloth, I’d use the machine to trim and enclose the seams at the edge of the fabric so they don’t loosen. She paid me and my brother ₦1 coin for every cloth we weaved. This was in the late 90s.

Her customers even started requesting me specifically to weave their clothes because I always did it neatly. It didn’t mean I was swimming in money, though. I had to use my “salary” to make up for how little we had to buy food or snacks in school.

So, no allowance?

What does allowance mean? My parents, my three brothers and I lived in a one-room apartment in Mushin, and things were tough. My dad had an electronics shop, so while my brother and I helped my mum, my other two brothers had to help my dad. But I stopped going to my mum’s shop when I entered secondary school.

Why?

I had to make more money to take the burden off my parents a little. I got a job serving food at parties during the weekends. All that involved was wearing my one white shirt and black trousers and entering any party to ask them if they needed extra servers. This typically paid ₦600 and a plate of food. That was also when I started spending less time at home.

Did something happen at home?

Not really. In Mushin, it was an unwritten rule that children — especially boys — started hustling when they’re a bit older. Plus, I realised from a young age that we were really poor, and I was focused on being independent and doing something different with my life.

When I wasn’t at school, I did one odd job or another. I once worked at a cloth printing shop that paid ₦800 weekly. That money meant my parents didn’t have to worry about what my younger siblings and I ate during the day because I always bought something for them, no matter how small.

Sometimes, I’d sleep at friends’ who lived close to the shop to save transport costs or stay over in church.

How often did you sleep at the church?

Quite often. My family attended a white garment church, and anyone familiar with how these churches run knows that there’s almost always a programme happening at any given time. I was also really prayerful, so I felt right at home. At that stage in my life, I knew God had to come through if I hoped to change the cycle of poverty I was born into. Throughout secondary school, my life was a church-school-hustle cycle. It was even in church I met the person who almost made me his bus conductor.

Why almost?

I’d just finished secondary school and was in the middle of applying to universities. I needed money, and I noticed that one of the elders in church had recently bought a danfo, so I went to him and offered to be his conductor. He agreed, and I was supposed to start the following week when I got admitted to the university.

What year was this?

2007. I didn’t take the admission, though.

Why not?

The school fees. It was a university in one of the western states that the governor had just founded. I was even meant to be part of the pioneer computer science students. But when I heard the fee was ₦200k, I had to give myself sense. Luckily, I had another offer to study civil engineering from a federal university, and tuition was ₦10k. I could afford that, so I took it.

It sounds like you were pretty much responsible for yourself at this point.

Yes. I’m good at mathematics, so I found a way into tutoring gigs. My first client was a classmate’s mum whom I met when I visited him at home — they lived close to the university. I noticed his 13-year-old brother was struggling with his maths homework, so I helped him.

His mum said I was good with explanations and asked if I used to teach. I didn’t, but I said yes. On the spot, she offered me ₦5k a month to tutor him thrice weekly for an hour. The first time I received my pay, I bought sardine bread to celebrate.

That’s double what you were earning at the printing shop. How did that feel?

You can’t understand the feeling. It felt like the easiest money I’d made because I made it doing something I liked to do.

Do you know I was the first person in my family to attend university? My elder brother was still battling JAMB when I got admitted. I honestly believe prayer was what allowed me to break through to university, so I found a campus fellowship right from 100 level and became active there. I stopped attending my white garment church because I felt more at home in fellowship and became more grounded in scripture. It turns out it was God placing me there.

How do you know?

During a joint fellowship conference when I was in 200 level, I heard God tell me he was calling me to a life of service. I assumed that meant serving in the fellowship as an executive. So, when I was elected into an executive position a few weeks later, I wasn’t surprised.

However, serving as an executive meant I’d have less free time and more responsibilities. By this time, I had three steady clients for my tutoring gig that fetched me ₦25k/month in total. That was my entire income source. It was difficult, but I had to stop two out of the three gigs, so I’d have time to serve.

But how did you manage?

Honestly, I don’t even know. I went from ₦25k to ₦8k, and things didn’t look too good. I’d grown up with this hustle mindset, but God was teaching me total dependence on Him. I trekked on some days and did wash and wear a lot, but God came through for me. I never delayed my fees throughout my days at university.

In fact, it was in uni I learnt generosity. I’d give people all the money in my pocket, knowing fully well I’d have to trek to my off-campus hostel. Uni was a teaching period.

So, what happened after?

I got an internship at a construction firm that paid me ₦90k per month immediately after graduation in 2013. My first salary was paid in cash, and I entered the market immediately to get some work outfits.

I had enough to take care of myself and send money home sometimes. When NYSC came along six months later, I was posted to a neighbouring state, but since I wasn’t too far, I’d visit the firm during the weekends to do some work on the site. They paid me ₦15k every weekend I came around. My PPA paid ₦20k, and NYSC paid ₦19,800. Most of the time, I ended the month with almost ₦100k. I was a proper big boy.

But then?

After NYSC, the construction firm offered me a full-time position for ₦150k per month. I was so excited and said yes on the spot. But I resigned after two weeks.

What happened?

God told me that wasn’t where he wanted me. He’d actually been reminding me towards the end of my NYSC year of the word he’d given me about being called into a life of service. But I struggled. I felt I’d sacrificed in university, and it was now time for me to make money. After all, I’d be in a better position to serve if I had money.

So, I stubbornly took the construction job, but I had to leave soon after because I wasn’t at peace. I went back to the mission in charge of my former campus fellowship and started volunteering there.

How much were you making?

₦5k.

Like, per day?

Per month. Volunteers were only entitled to stipends because they were also allowed to do other things for money, but that’s all I did. I lived at the mission house, so accommodation was free. I did that for about two years before deciding to become a full-time missionary.

What did that entail?

I already volunteered with the mission, so I had a good sense of how it worked. I spoke to the missionaries I was volunteering with, and they recommended me to the mission heads for full-time employment.

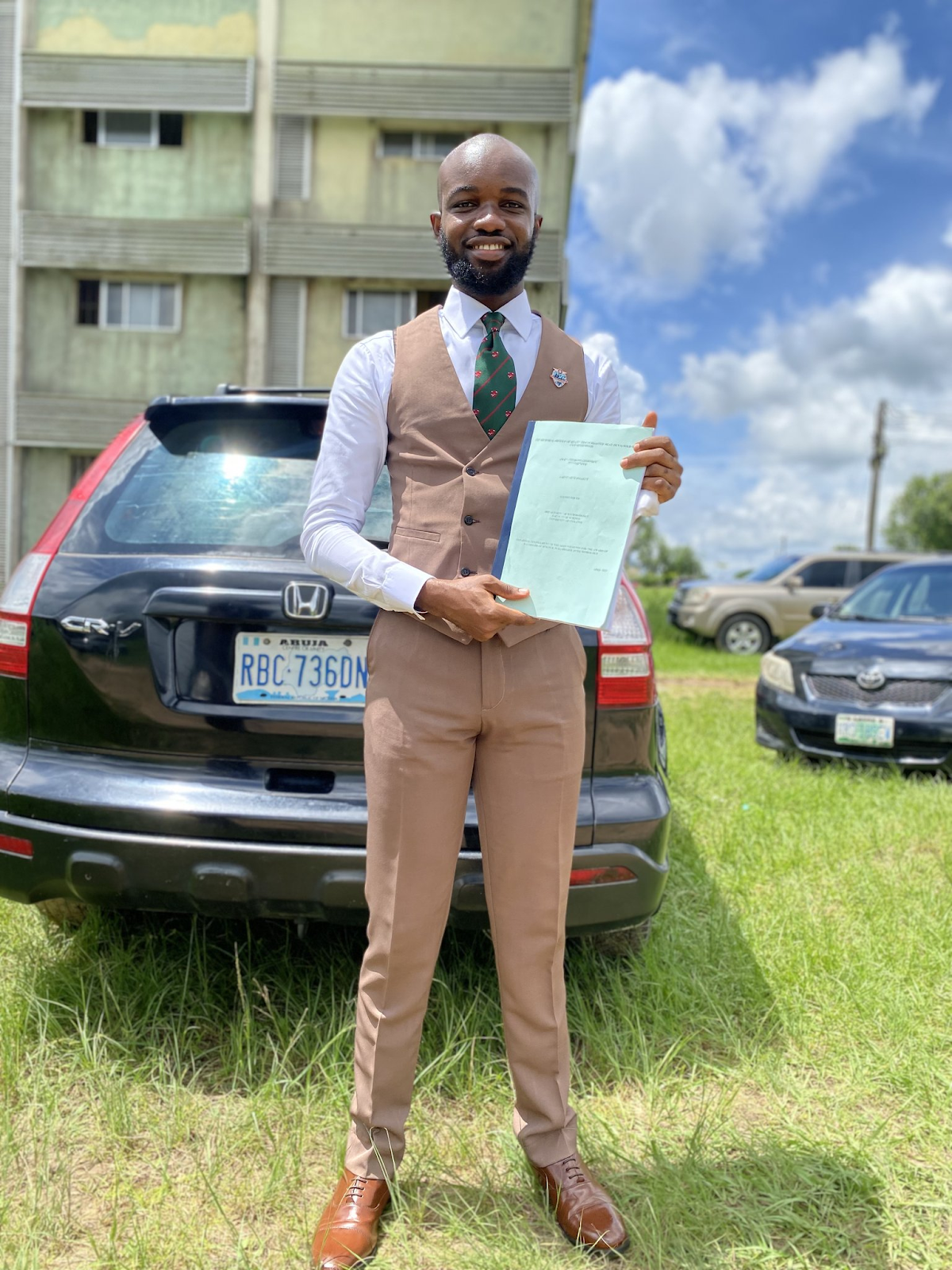

In January 2017, I travelled to the mission headquarters in the North for a six-week training. At the end of the six weeks, I got posted to the state I currently serve in and became a full-time missionary.

How much money does a full-time missionary make?

As a new missionary, I made ₦40k per month. But in the six years I’ve been here, I’ve gotten a few promotions. We earn promotions through appraisals and the number of years worked, just like a normal organisation — and my salary is now ₦49k.

How does the mission make money?

Like most missions, income is usually gotten through donations and tithes paid by people who’ve been blessed by the mission. It’s from that money I get paid my salary and fund other ministry needs like conferences and even supporting less privileged students with school fees. Each missionary is posted to a state in Nigeria where they oversee the mission’s affairs in the different campus fellowships in the state. I’m like that state’s pastor, and I help organise evangelism outreaches and training programs to ensure young Christian students are properly discipled into the knowledge of Christ amidst the different distractions of today’s world like social media and the questionable fashion choices people make now.

In addition, I do most of the state’s fundraising to meet training and ministry needs. So if there isn’t enough money in the state’s account to pay my salary at the end of the month, I go without it.

Does that happen often?

It does. I’ve once gone four months without a salary. It’s almost normal. Of course, as a full-time missionary, I can’t do anything else for money.

What was your family’s reaction to becoming a missionary?

For the longest time, my parents thought one evil spirit from our village was what made me leave a promising career to carry Bible around. When I first started volunteering, they reported me to my elder brother, even though he had relocated to South Africa then. He called and tried to speak sense into me. Fortunately, he’s also a Christian. So while he didn’t fully understand why I couldn’t serve God while keeping a regular 9-5, he understood that I had to respond to God’s calling.

Now, my parents are somehow resigned to it and just call me “Pastor”. When I was preparing to get married in 2020, they called my wife aside to ask her if she was sure she wanted to marry me because I make close to nothing. They didn’t know my wife had also volunteered with the mission as a student. She assured them she knew what she was doing.

What about your in-laws? Did they know about your job?

My wife’s father is late, so I only have a mother-in-law. She knows what I do, but I don’t think she knows exactly what I earn. My wife didn’t make it a subject for discussion. It was just like, “This is the man I want to marry”. I honestly need to give my wife a shout-out. She’s the reason her uncles didn’t bill me unnecessarily, and we had a small budget-friendly wedding.

Does your wife work with the mission now?

Oh no. The mission doesn’t allow couples to work together because work typically takes us away from home for considerable periods. My wife’s a nurse, and she currently earns about ₦100k per month.

How do you plan your monthly expenses if you aren’t sure of a salary?

It involves a lot of trust in God, and I really don’t expect people to understand. I remind myself daily that I didn’t call myself here; God did. So, He’s more than able to provide what I need per time. Sometimes when I’m really broke, I’d just get a random credit alert from a former student I trained in the fellowship. I move with this confidence that I have God and can never be stranded.

My wife is also really helpful and chips in when she knows I have nothing. I also like to plan ahead when I get money. So, salary can come today, and I’d just hold a little of it and send the rest to her for food and other expenses.

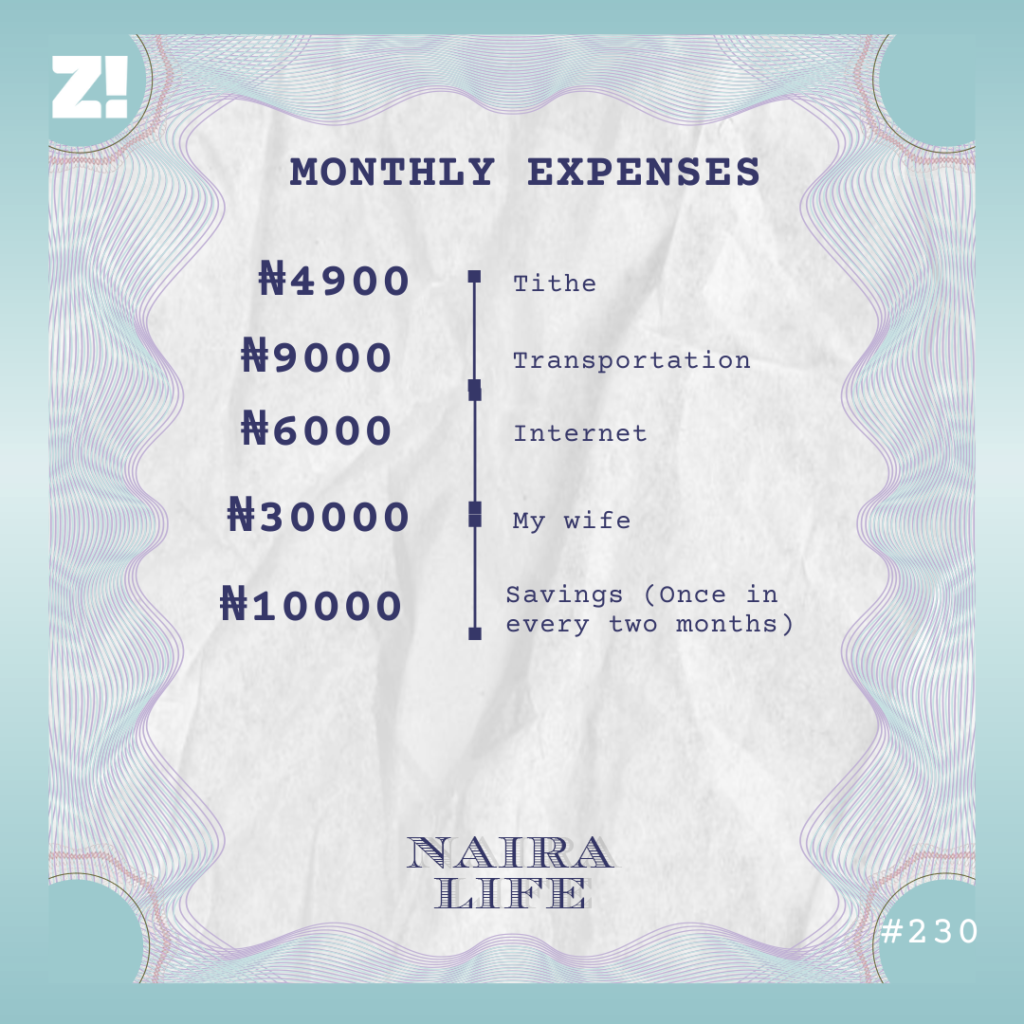

Can you break it down?

I don’t pay rent because I live in the state’s mission house. The mission also pays for the electricity bills. My wife contributes about ₦50k monthly to help fill out any gaps.

What do you use your savings for?

There’s this ajo contribution my wife and I are a part of. We pay ₦10k every month to collect ₦120k at the end of the year. So I pay one month, and she pays the second month. We’ve done it since we got married and we typically use the large sum for any need we have at the time of collection. We bought a deep freezer with the last lump sum amount we got.

What’s one thing you want right now but can’t afford?

A car. My work takes me around the state every week. When I calculated my public transport expenses, I realised I’d spend less money to fuel a car for those movements. Plus, my wife is pregnant. Will she be flying okada when she becomes heavy or when she eventually gives birth?

I priced a Toyota Matrix recently, and I was told to pay ₦2.4m. I don’t have ₦1m, but I know I’ll have a car soon. How it’ll come, I don’t know yet.

On a scale of 1-10, how would you rate your financial happiness?

7. I don’t have much, but I’ve never been stranded, and I feel fulfilled serving God. Just last week, I counselled a student who was planning to commit suicide because of a masturbation addiction and led them back to Christ.

God is touching lives through me, and I know he just got started. I only wish I had more to give my wife all the enjoyment she deserves.

I have to ask. Do you see yourself being a missionary forever?

Not really. I know God wants me here now, but I’m also prepared for when he tells me to move. One thing I’ve consciously done is make sure I still have relevant skills even if I’m not using them. I’m currently taking a Product Marketing course just because I found it interesting. If God decides to move me back to the corporate world, I won’t be useless.

If you’re interested in talking about your Naira Life story, this is a good place to start.

Find all the past Naira Life stories here.