As told to Hassan

Let me tell you how it started. I woke up one morning in 1999 and my eyes were itchy. The more I rubbed, the more painful they got. When I eventually stopped rubbing, whitish-yellow fluid stuck to my fingers. Pus. It was supposed to be one of those mornings I ate cornflakes and watched cartoons; instead, I was wide awake, running to my parent’s room.

My parents panicked. One minute, I was showing them my eyes, the next, we were at the hospital. I don’t remember the drive. After some eye tests, we were told my eyes were jaundiced, and I needed to do more tests. One blood test later, I was given a sickle cell diagnosis. I was four.

My first thought was “what’s that?” I turned to my dad to ask, but his pupils were distant, lost in thought. And while I don’t recall what my mum was doing, I’m sure she must have been praying, hands clasped, eyes closed.

My story had started without me realising it. I would slowly come to understand that my life had changed. At first, all I had to do was be careful. But then I attended a birthday party, and because I wanted to feel “normal,” I ended up dancing until I landed in the hospital.

That birthday incident changed everything.

The first thing to go was my freedom. I now had rules: no playing in the rain, check. No swimming, check. No birthday parties, double-check. My childhood became a recurring theme of sitting out activities.

In the rare event that I was invited out, my friends would spend the entire day worrying about me. I was never able to enjoy those outings.

This continued until I got into university. As a child, my family took turns taking care of me. But in school, there was nobody to do that for me. I had to look out for myself, in addition to the tedious school work.

There is nothing more stressful than living with sickle cell as a Nigerian student. For non-sickle cell people, uni stress was just uni stress. For me, uni stress meant hospital visits, missed tests and exams. In some cases, I had to write exams from the hospital bed.

Keeping friends was also a private hell. My friends would say, “Precious, do you think you should come out with us tonight, because of your health?” All I heard was “You’re going to slow us down”, “We’re not going to have fun because of you”, “You’ll land in the hospital.”

Dating was another thing entirely. I’d meet the most interesting people, and the moment I disclosed my condition, I’d get long messages saying: “I think you’re amazing, but I don’t think I can handle this.”

The messages broke me and made me blame myself. Then I travelled to the UK for my masters in 2018.

The care I received changed my perspective. During hospital visits in Nigeria, health professionals would say, “Weren’t you here last month?” or “See you soon.” I would feel guilty and apologise every time I fell sick. In the UK, health professionals would remind me that I had no control over my health. At some point, they asked if I fully understood my diagnosis. They “educated” me about sickle cell, but more importantly, they made me feel seen by really listening to me.

I started to live more freely. I went out if I wanted to. My motto changed from “if I fall sick, I’ll ruin people’s plans” to “if I fall sick, I’ll go to the hospital.”

I enjoyed this freedom until I returned to Nigeria. There was a clash between my old identity and my newly-won identity. I had gone from the shielded child to someone comfortable expressing herself. I no longer saw myself as a sick person who couldn’t have fun. This led to friction between me and family members unwilling to understand and respect the new me.

At this point, it had been more than 15 years since my first sickle cell diagnosis. There was a new Precious. Someone who spoke out against insensitive religious people, people who told me to pray away my sickness or that children of God didn’t fall ill. Or the ones who told me to just declare the word of God: as if it were that easy.

For a while, these comments almost made me feel less of a Christian, like my faith was not strong enough. I went from being a religious person to resenting the church. I started to despise the so-called religious Christians.

Another set of people believed I was exaggerating the pain. They expected me to be used to it by now. Their insensitivity annoys me, but that’s a story for another day.

I’m choosing to focus on the positives, like making quality friends. Friends who have an unspoken rule: “When Precious is in the hospital, we’ll take turns looking after her. No questions asked.” Friends like Salem King, aka chief caretaker, who says, “Precious, you’re not a burden.” Friends who make my journey feel less lonely by showing up for me.

My journey has been bittersweet. Living with sickle cell has given and taken from me. For someone who didn’t start making friends early, I now have the most amazing friends in the world.

When you come from a large family [six siblings] like mine, you crave independence quickly. This need is heightened if you’re the only one living with a long term condition. You grow up angry. Angry that your family members don’t understand you. Angry that no one stands up for you. Angry about your search for miracles from one church to the other. Angry that despite everything, you still need your family’s help.

Living with a chronic illness means I can’t refuse help from people no matter how independent I get. I teach emotional intelligence for a fee, and the fee pays for my drugs and a few hospital bills. Still, there are things I can’t do on my own. I can’t drive myself to the hospital when I’m having a crisis. I can’t look after myself when I’m on admission.

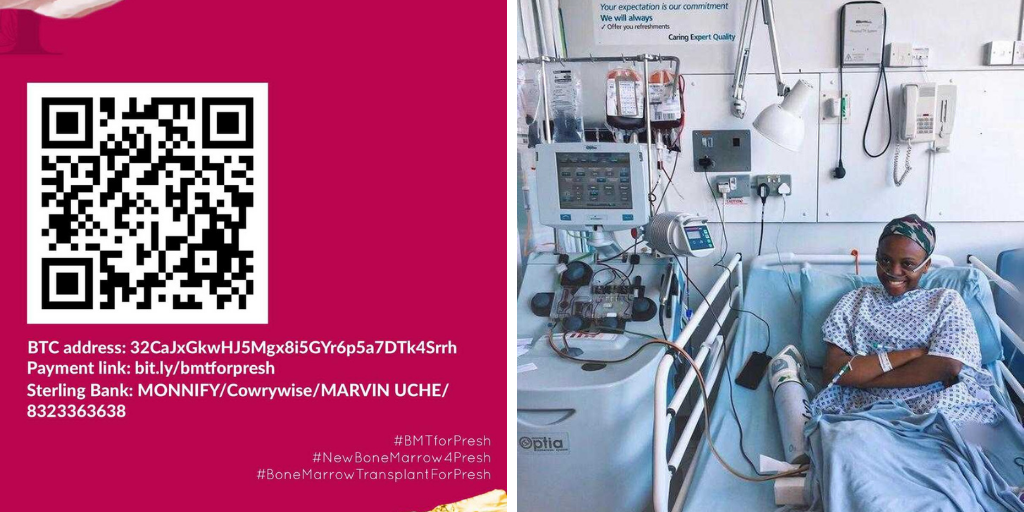

I’m tired of depending on people, but there’s nothing I can do. In the first quarter of 2021, my friends started a GoFundMe. It’s for a bone marrow transplant to give me a new genotype, curing me of sickle cell.

Immediately I announced this development, I got heat from two sides. Firstly, from my conservative northern family. They were furious that I embarrassed them by “announcing” my illness to everyone. The Christians were also enraged because they felt I betrayed God by choosing to follow science.

They’ll all be fine.

I’m doing this for me. I’m also doing this based on my newfound knowledge of God. He’s understanding, kind and he loves me.

I’m not naive to think that it’ll be smooth sailing. But I’ll pick the pain of surgery and raising money over the pain of surviving sickle cell for 25 years.

I’m going to fight with all I’ve got — till the end. For myself and my friends who’ve been through everything. For everyone who has suffered with me, held my hands and cried with me.

I’m doing this for us.

And when I finally get my surgery done, I’ll throw a Precious 2.0 party. I can’t wait to finally start living without thinking I’m a burden to people.

I’m going to learn how to swim, how to ride a bike. I look forward to dancing in the rain without fear. Most importantly, I’m going to reclaim my childhood.

Click here to donate to Precious:

GoFundMe: https://gofund.me/77dde500

Flutterwave : https://flutterwave.com/pay/crg78jsohnxo