The Elevator is a limited Zikoko series that details the growth of young successful Nigerian women. We tell their stories every Tuesday by 12 p.m.

From writing, acting and directing school plays as a teenager, Nana Darkoa learnt to speak up about pressing societal issues. At 16, she knew she wanted a career in communications and she sought it. Along the line, she found feminism and learned that personal issues are just as political as societal issues. This led her to write a book about the sex lives of African women. Nana Darkoa is a 44-year-old feminist writer, and in today’s episode of The Elevator, she talks about her journey to becoming a communications specialist whose core work focuses on liberating African women.

When did you develop an interest in writing?

I used to love acting. As a teenager, I acted in school plays. I also wrote and directed those plays. Acting at that age gave me more confidence to be the kind of person who speaks up about issues. At parent-teacher-student meetings, I would raise issues that no one had the guts to talk about, like the excessive punishment our teachers gave us.

Did you know what you wanted to be when you grew up?

I wanted to be an actress, but my parents wanted me to become a lawyer. By the time I was 16, I decided I wanted to work in communications. I didn’t exactly know what it meant to have a communications degree, but I imagined it’d be glamorous. I thought I’d be this high flying corporate woman who’d spend her evenings at fancy restaurants drinking wine.

LOL. Did your parents agree with this dream?

Yes, they did. I moved to the UK to study communications and cultural studies after secondary school. Cultural studies introduced me to feminism and that changed the direction I wanted to go with my career.

How?

I decided to go on a super feminist path. In cultural studies, I was introduced to the work of black feminists like bell hooks, Alice Walker and Patricia Hill Collins. They made me aware of myself as a black African girl. I’d never had to think deeply about race when I lived in Ghana. Reading books by black feminist authors helped me not just see myself but helped me navigate my life in the UK.

For example, I never understood why my mum had to make my dad dinner. I always wondered why he didn’t just make it himself. Studying feminism helped me understand the role of patriarchy in the society.

What happened after school?

After my first degree, I got a job as a communications officer at the Metropolitan Police Service. It involved being a dispatcher: answering calls and sending the police to deal with issues that arose around the city.

I worked with them for seven years. During that time, I did my master’s in Gender, Development and Globalisation at the London School of Economics and Political Science part-time. I was able to work in shifts and go to school during the day. Being born in the UK meant I could pay home fees, which allowed me to go to university. Subsequently, I moved back to Ghana in 2006.

What does your degree mean for an African in Africa?

Well, I got a job with the African Women’s Development Fund, the first pan-African feminist grantmaker on the continent. I started off as a communications officer and then a communications specialist, I worked there for about seven years before joining the Association for Women’s Rights in Development, a global feminist member movement support organisation, as a women’s rights and media coordinator. It was the perfect role for me because it combined feminism with communications. We work with a range of feminists in the social justice movement to co-create a world that every human being would like to live in — a world free of oppressive systems like capitalism and religious fundamentalism.

In 2015, I got promoted to communications manager. I was even happier when I got another promotion to become a director of communications. A few months later, I changed roles to director of communications and tactics. Working in this role has taught me so much about being a feminist.

Can you share some of that knowledge with me?

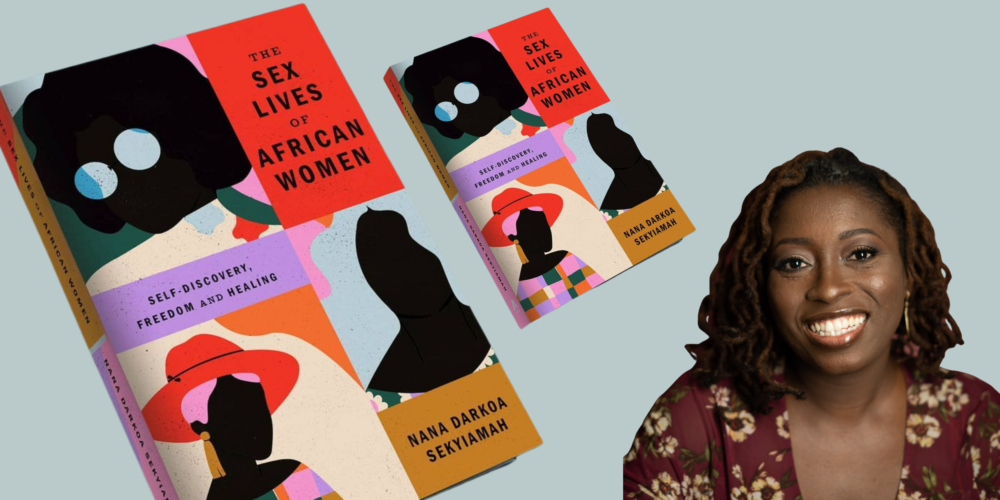

One of the first things I learned about feminism is that personal issues are just as political as everything else. As I delved more into feminism and my feminist beliefs strengthened, I wanted to challenged the personal experiences of women that are considered taboo to speak about. That’s why I decided to write a book I n 2014.

Ouu, what’s the book about?

The book is a collection of stories about the sex lives of African women. It took me about five years to write it. I did my first interview in 2015 after a woman slid into my DMs to ask questions about sex because she was confused about her own sexuality. She was attracted to women but didn’t know what that meant for her. Was she bisexual? Was she a lesbian? As we spoke, I realised she could be a part of the book and from then on, I continued to talk to other African women about their sex lives.

How did you find the other women in the book?

It was a journey. I travelled a lot for work before 2020, so I decided that everywhere I went, I would find at least one woman I could interview for my book. In the beginning, I did face to face interviews with women in Zimbabwe, Sao Tome, Nigeria, Senegal and London. I asked questions about their early experiences around sex and how abuse or childbirth affected their pleasure.

When the pandemic hit in 2020, I switched to Zoom meetings. That same year, I got my book deal and so I had to finish the book. I put out calls on Twitter and on my blog, asking people if they wanted to be interviewed. You’d be surprised at how much women want to talk about sex — I had a lot of women in my DM wanting to be interviewed.

What was the selection process like?

I interviewed women from diverse backgrounds, like women who were sex workers or had been married or only had one sexual partner. I’d interview them, transcribe the interview, and then let the story breathe before rewriting it in the first person. I wanted people to resonate deeply with the women whose stories they were reading. There was only one woman I interviewed that I didn’t include in the book, and it was only because her story wasn’t a good fit for the book.

It was a lot of fun to talk to women about sex. It could only have been feminism that allowed me to have those conversations. I’ll always be grateful I found it because once I did, I became hooked. I was like, “I have found my path in life and I shall not stray from this course.”

LMAO. Tell me about your path now.

I recently stepped down as the director of communications and tactics for the Association for Women’s Rights in Development. One of the major reasons I’m leaving is so I can have more space in the daytime to write. I now have a child, so it’s gotten a bit harder to manage my time. Now that I’m no longer working full time, my plan is to build MAKEDA PR, my communications firm for feminist movements. I already have some consultancy work lined up and I’m excited about that. I’ll also do more reading and research alongside running sexual freedom workshops.

Interesting. Would you say you’re at the top of your career?

Not really. I know I’m at a good place in my career, but there are a few things I’d like to happen before I can say I’ve peaked. For example, I want to publish a second book that’ll win many awards, and I’m already working on it. I’d also like to have a successful podcast and to grow my communication consultancy firm. When these things come together, ask me that question again.

Neat. What’s your working process like?

When I was writing a book, I also had a full-time job, so I had a tight schedule. I used to wake up at 5 a.m. so that I could start writing at 5:15. I’d write for two hours before I went to work. After work, I’d take a shower, sit down and write. That was my working process until I had my child. Luckily, I got a generous parental leave of six months. The leave and my live-in nanny helped me navigate writing the book as a new mum.

Now, I can’t wake up at 5 a.m. to work because of my child. I also can’t work as many hours as I used to. This is why I had to quit — I need more time for myself.

I hope you get the time you need. I’m curious about how you get through writer’s block.

I have never experienced writer’s block. I may not feel like writing, but there’s always something I can write about. So for me, it’s more about finding the space and time to do what I need to do.

I feel you. If you could change anything about the trajectory of your career path, would you?

No. I’ve had a great career trajectory, and I feel it’s what I needed to become who I am today.

Love that energy. If you could tell your 15-year-old self something, what would you say?

I’d say don’t judge your classmates that are having sex. Take a chill pill and mind your business.

Subscribe to our newsletter here.