Okeoghene (32) knows how difficult it is to rebuild after losing everything.

He shares how he found a rewarding career in art and graphic design despite his parents’ disapproval, becoming successful, and hitting a creative wall after losing ₦17m. Now, he’s trying to start over.

As told to Boluwatife

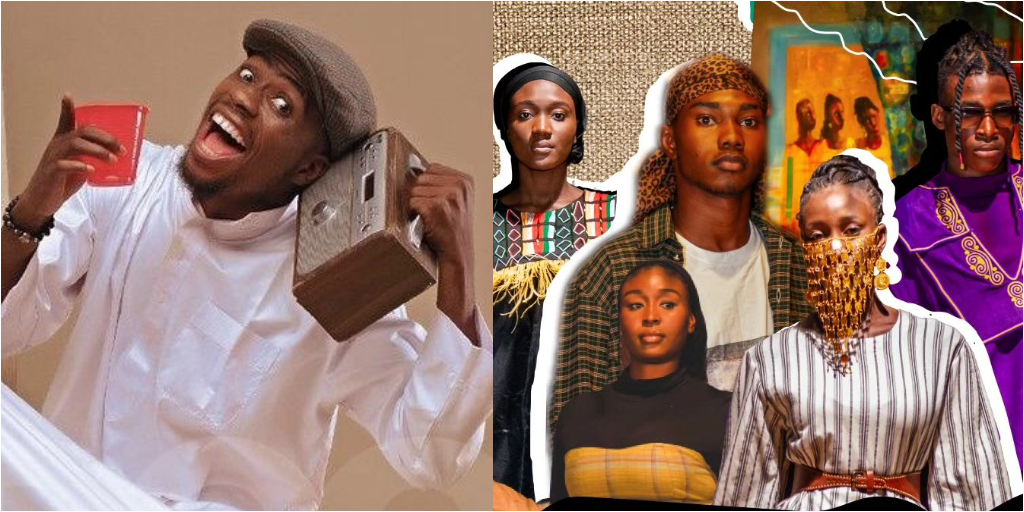

Image: Okeoghene Efeludu

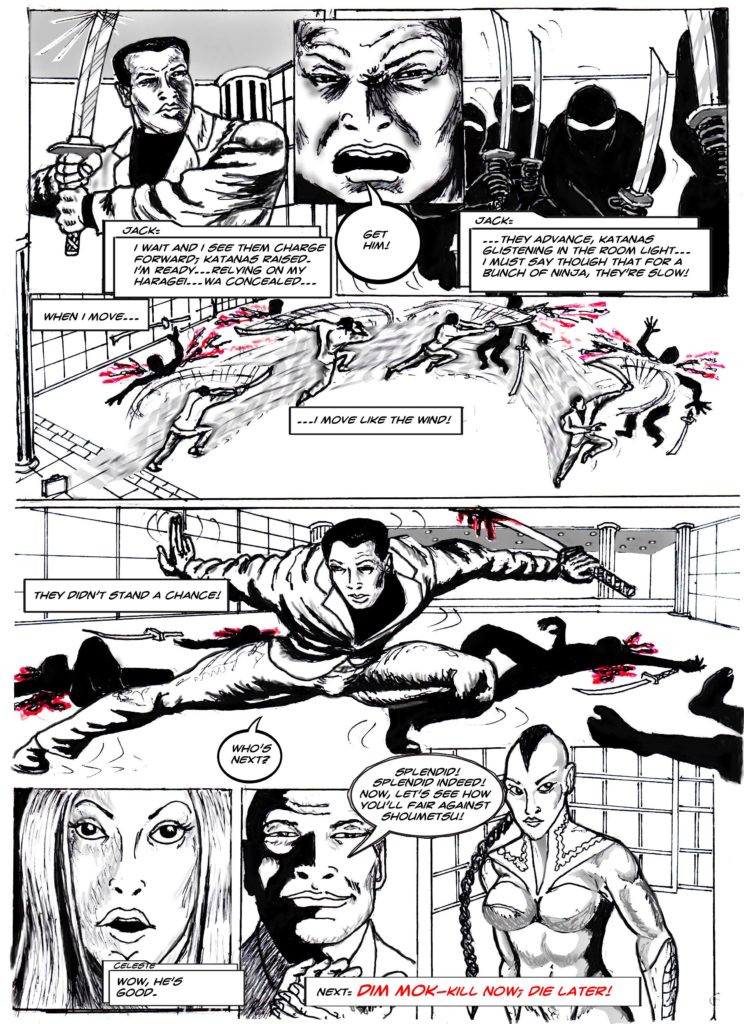

I loved cartoons as a child. The late 90s and early 2000s Cartoon Network raised me, and I loved recreating the characters I loved — Samurai Jack, Dexter’s Lab and Courage the Cowardly Dog.

My drawings were just a fun hobby. But I stopped drawing when my dad saw a Justice League-inspired comic I drew in JSS 2 and tore it up. For him, drawing had become a distraction and prevented me from improving my studies.

I didn’t draw again for a long time. Instead, I focused on doing what my parents expected of me.

First, it was sports. I ran track and played basketball in secondary school. I was on the path to getting a basketball scholarship to a university in the US when a drunk driver hit me and broke both legs. I was 16, and that was the end of any dreams of a sporting career.

Since I couldn’t pursue a US university admission anymore — my barely middle-class family couldn’t afford it without financial aid — I focused on getting into a Nigerian university. That took three years of trying out different things my parents wanted.

Between 2009 and 2012, I was admitted into three different universities to study courses ranging from computer engineering to even almost getting recruited into the Nigerian Defence Academy. I wasn’t interested in them.

I wanted to study archaeology, but like typical Nigerian parents, my parents weren’t having it.

I eventually studied computer engineering, networking, and cybersecurity at NIIT, a talent development institution. By 2015, I was working in tech support, fixing laptops, and working on telecommunication masts.

In the same year, I had a wake-up call. I asked myself, “What do I really want to do?” I’d spent all these years doing different things, but when would I eventually do something for myself?

At that time, I was a fan of the Hip-hop culture, and graphic T-shirts were a big part of it. However, the 2015 graphic T-shirts had phrases like “Ama Kip Kip” and “My money grows like grass.” I hated those shirts, and I wanted to create something better.

There was a problem: I’d stopped drawing for so long that I wasn’t sure how to start. My cousin, Precious, was an artist, so I called him. We agreed that I’d describe what I wanted to draw, and he’d make it happen.

But there was another problem: How would I convert these drawings on paper to something digital I could print on shirts?

I knew a graphic designer at a cyber cafe I frequented, and when I asked how much it’d cost to turn the drawings into digital designs, I decided I was going to learn graphic design.

I bought Corel Draw tutorial CDs and began teaching myself. It looked like sorcery at first, but I soon got the hang of it. My sister’s boyfriend gave me my first gig, paying me ₦2k to design a small flyer.

My parents were pissed when they realised I was spending all my time with graphic design. It took an uncle’s intervention for them to tolerate the fact that I’d abandoned everything to pursue a career in graphic design.

I also got my first graphic design job in 2015, making ₦10k/month at a printing press. Asides making me a better designer, that job taught me a lot about the T-shirt business.

After a few months, I left the job and began designing my own T-shirts. I borrowed ₦20k from my sister and printed my first samples; then, I got a gig to supply T-shirts for a street jam party. It didn’t take long before people knew me as the “T-shirt guy.”

In 2016, I started posting my graphic designs on social media and got a few freelance gigs here and there. Of course, I made some of the obligatory rookie mistakes most new freelancers make.

I remember not negotiating for a branding gig because I got it through a friend. After I completed the gig, they asked for my fee, and I said ₦20k. They laughed and sent me ₦5k. Another client told me they got someone else for the job after I’d already gone halfway through the project.

These experiences taught me to treat design as a business. So, I learned to draw up guidelines and collect part payments before working on any project.

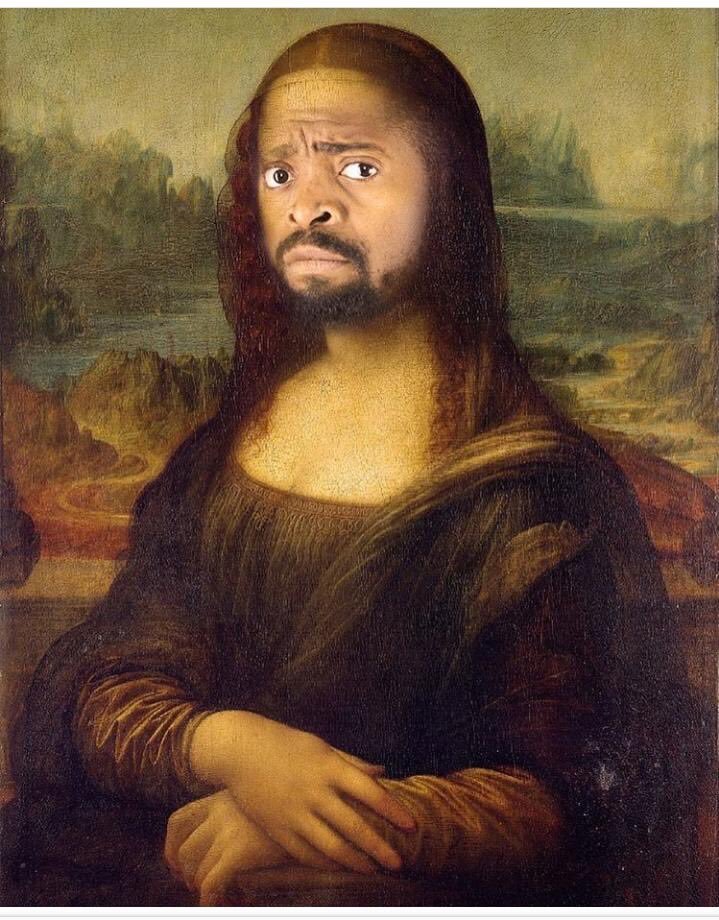

Things took off from there. I got regular jobs, and with them came the confidence boost that came with being really good at what you did. I even went viral in 2018 for doing a photo manipulation with King Kong and the UBA building at Marina, Lagos. It was just a random design, but UBA reposted it, and I got tons of followers and even more gigs.

Digital art gave me my first big break in 2018. Someone contacted me on Instagram and requested a canvas print for her boyfriend. I randomly charged ₦300k, and she negotiated to ₦280k. I honestly thought the most I’d get was ₦50k.

After I completed the job and got paid, I used about ₦120k to go on a mini vacation to Ghana. It was my way of coming to terms with the fact that I could live a good life and make good money from design.

And I did make good money between 2019 and 2021.

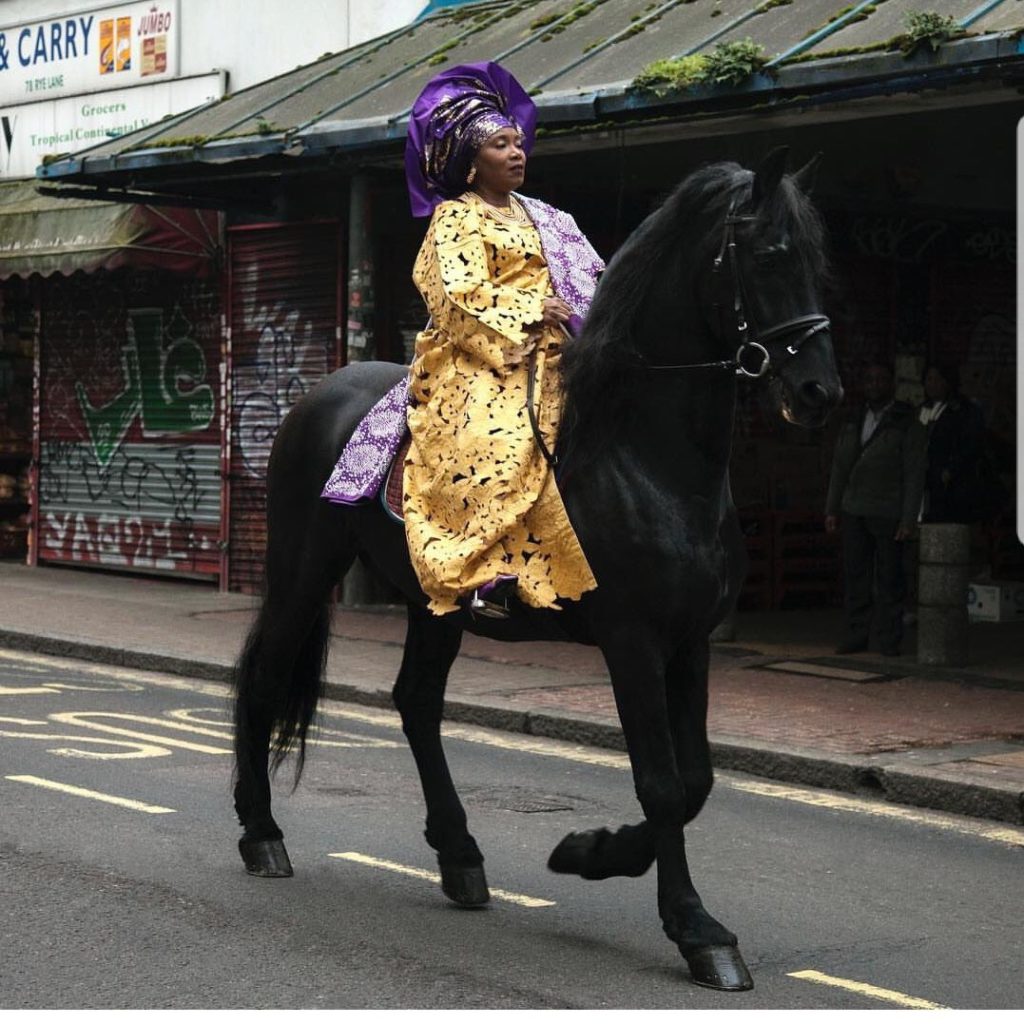

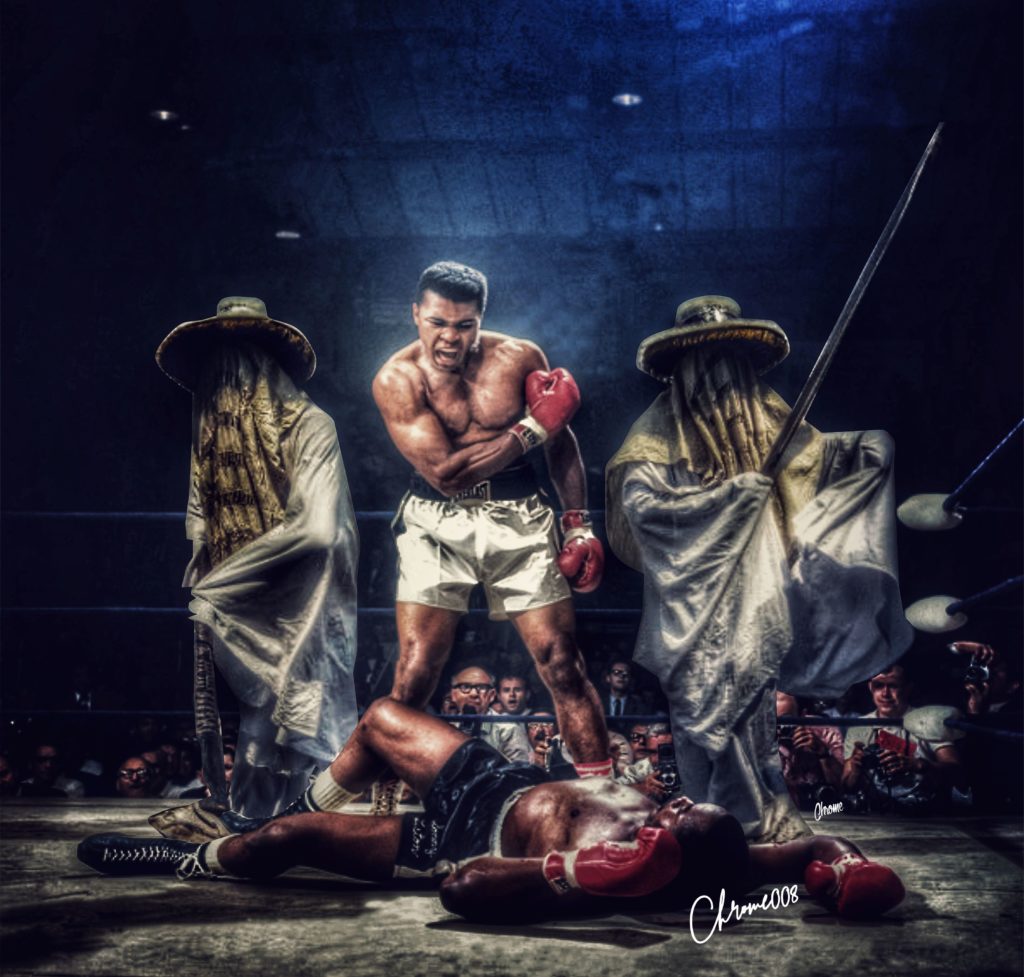

My designs caught attention online because I had a thing for mixing Afrocentric and urban designs with pop culture. I got a job with a US creative firm that paid six figures and collaborated with several national and international brands.

Image: Okeoghene Efeludu

I was on a financial high, and while I initially just spent money as it came, I decided to become serious with my finances and began consistently saving in 2020. That turned out to be helpful because 2020 was a slow year due to the pandemic and some health issues. I quit my 9-5 and went fully freelance.

However, things picked back up in 2021. I secured a collaboration with an international drink brand and was on retainer for about five other brands. I even formed a small company and got a few young designers to work on the projects I couldn’t take on because of time constraints. I was a proper creative director.

Then, 2022 came, and that’s when my problems started.

I invested some of my money in a friend’s delivery business. One day in February, one of our bikes developed a fault, and the rider got into an issue with area boys. I was close by, so I decided to go there to sort it out. However, rather than de-escalating the issue, a fight broke out when I arrived, and my phone got stolen in the scuffle.

I wasn’t bothered by the theft at first. I called my network provider and asked them to block my line. The bank account linked to the line was my main savings account, so I also called my bank and deactivated my ATM card — basically everything I was supposed to do after losing my phone.

I couldn’t retrieve my SIM for about two months because of the NIN wahala. I eventually retrieved it without going to my network provider’s office. It turned out you could just meet a regular person on the street, and they’d link your line to a new SIM card. I was shocked that was possible, but I guess it explains how the people who got my stolen SIM were able to impersonate me.

When I put the new SIM card into my phone, I started receiving strange debit alerts. Almost immediately, random people began calling and accusing me of defaulting on loans. I didn’t know what was happening.

I found out that blocking my SIM card didn’t prevent it from receiving text messages. The thieves could still use USSD codes on the SIM, and they cleared my entire ₦17m savings. I didn’t realise earlier because I never touched the money in that account — I had a separate account for everyday use.

They also used USSD to find my BVN and collected loans—about ₦300k in total. I thought the loan companies disturbing me was the worst part until the Economic Financial Crime Commission (EFCC) flagged my bank account and summoned me.

Apparently, the thieves had sold my SIM card to a 419 syndicate, and those ones used my details to open different accounts. The next few months involved multiple police station and court visits to sign statements and swear affidavits that I’d actually lost my phone and SIM card. I also had to secure a court cease and desist order and involved the FCCPC to get the loan companies off my back.

When I eventually sorted that out, I had to face the reality that I’d lost everything. I was in a very wild state of mind. I was suicidal, mentally unavailable and couldn’t work. I couldn’t do anything from June to November except sleep and wake up.

In 2023, I decided to throw myself into work and try to make all the money I’d lost. It worked out for a bit — I got several gigs, averaging ₦400k – ₦500k monthly. I even got another 9-5 in October.

But I gradually realised I hadn’t properly processed all that had happened in 2022. I was spending so much because I was scared of saving and losing my money again. I’d also taken that job because I was trying to make money quickly again, but I was mentally drained due to the toxic environment. I was losing my creativity and starting to hate design.

I quit my job about two months ago and spoke to a therapist to process everything that’s happened. It doesn’t help that I’m trying to rebuild my life and finances at a time when the country isn’t even balanced. Inflation is literally making it impossible for me to build a safety net again.

It’s extra difficult because money plays an important role in my creativity. For instance, I like doing passion projects — murals, visual art pieces, and art recreations on the side. Those cost a lot of money, but they help me explore my creativity and create art I love. Sometimes, I sell these pieces, but it’s difficult to take that risk now because I don’t know where the money will come from.

I’m now focusing on rediscovering myself as a creative person and figuring out how to love design without relying on a financial safety net. It hasn’t been spectacular, but I’m in a better place mentally, and I’ve learned to separate the money from the art.

I’m reminding myself that I don’t make art because of the money I want to make from it or what I hope to get. I create and design because I love it. It’s my life, and it shouldn’t stop because I lost everything.

NEXT READ: I Failed Out of Medical School After 5 Years, but I Don’t Regret It

[ad]