By: Pamela Adie

I didn’t grow up knowing queer people existed — not on screen, and not in real life. In the Nigerian films I watched as a child, queer people were either invisible or portrayed in deeply harmful ways. In Emotional Crack (2003), Rattlesnake (1995), and Men in Love (2010), homosexuality was shown as satanic, unnatural, even demonic. If queer characters weren’t possessed, they were mentally unstable, promiscuous, manipulative — outright evil. It wasn’t just cinema; it was a direct reflection of how society viewed us. And I took all of it in, without even realising the damage it was doing.

So, like many others, I grew up with no language or framework to understand queerness. I didn’t know any openly queer people, and I certainly didn’t see myself in Nollywood. I followed the script I was handed: I married a man. I wasn’t in love, but it felt like the “normal” thing to do — the thing that would make my family proud, the thing society expected.

It wasn’t until after that marriage began that I realised something was missing. I wasn’t attracted to men, not the way I was told I should be. That realisation shook me to my core. The marriage eventually ended, and from its ashes came something new: the truth of who I am.

I came out as a lesbian.

It was scary. But in the fog of self-discovery, I clung to what little visibility I could find. Ellen DeGeneres was one of my earliest sources of inspiration — and yes, I know she may not be the most ideal figure now, but back in 2010–2011, she was the only openly gay woman I saw thriving after facing adversity for her identity. That says a lot about the absence of Black, queer, African female role models — something I still think about today.

Then came the law. In 2014, President Goodluck Jonathan signed the Same-Sex Marriage Prohibition Act (SSMPA), a sweeping piece of legislation that not only banned same-sex unions but criminalised even public displays of affection and gatherings of queer people. I had just completed my master’s degree in the U.S. and was preparing to return to Nigeria. The timing was terrifying. The queer community back home was afraid, anxious, but also determined not to disappear.

That atmosphere — tense, resilient, defiant — was what I returned to. It only strengthened my resolve: if our very existence was under threat, then visibility was resistance. And stories were powerful.

ALSO READ: Bisi Alimi on How to Tell Queer Nigerian Stories in Nollywood

In that period of awakening, I started my blog: www.dizzlesbay.blogspot.com. It became a personal journal — a space where I documented my life as a lesbian from Nigeria. I wrote about love, heartbreak, family, rejection, acceptance, fear, and courage. I wrote my truth, and people responded. The blog grew a large following. But with time, I realised it wasn’t enough. The impact I wanted wasn’t happening on the scale I knew was possible.

In 2016, TIERs produced Hell or High Water, directed by Asurf Oluseyi. I attended a private screening of the film, and that’s where I met Asurf for the first time. It was a lightbulb moment for me — I saw, firsthand, that queer-themed films could be made in Nigeria. The seed was planted.

The following year, I took my first big step. I hired Asurf to join me as cinematographer for Under the Rainbow, Nigeria’s first lesbian documentary, which I produced and directed. It was a visual memoir — my own coming-out story laid bare: the good, the bad, and everything in between. It was deeply personal, but also deeply necessary.

Momentum was building. In 2018, TIERs released We Don’t Live Here Anymore, directed by Tope Oshin — another milestone. I was at the premiere, and I was moved. The following year, Walking With Shadows came out, starring my friend and secondary school classmate, Ozzy Agu. It was powerful. But as I watched all these films, something struck me: they were all centred on gay men. Where were the stories about us — about queer Nigerian women?

That question became a challenge: Why not me?

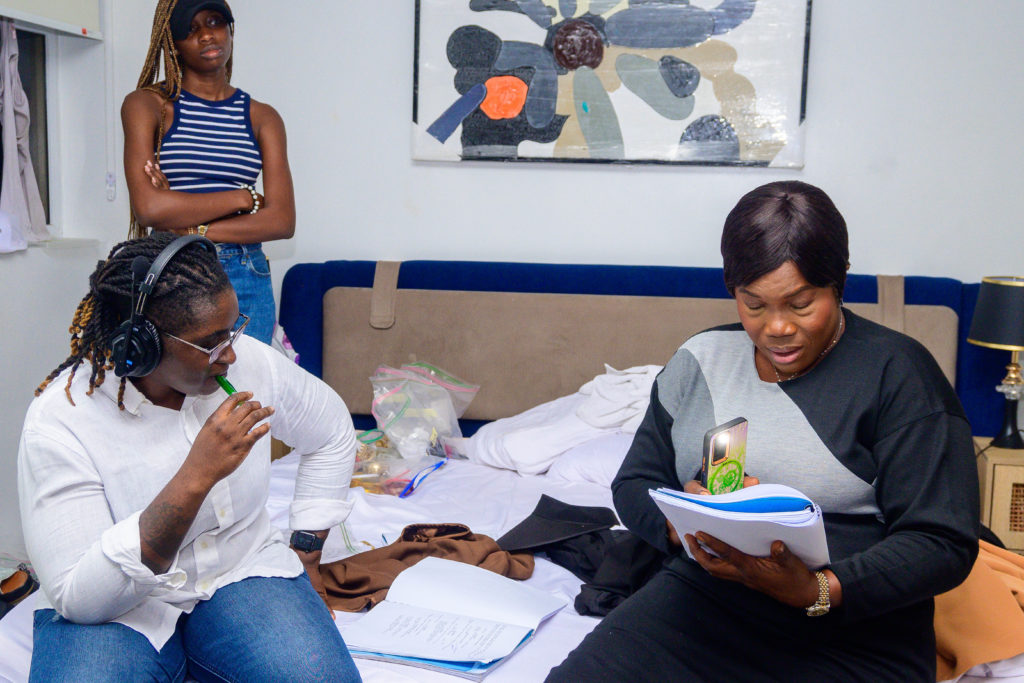

I started looking for funding to make a film that would change the narrative. Around that time, I met Uyaiedu Ikpe-Etim, who would go on to direct Ìfé. We shared a clear vision: we wanted to tell a story about two Nigerian women falling in love, without tragedy, without shame, without erasure. Just love. Pure and simple.

I produced the film through The Equality Hub, and we brought Uyaiedu on as writer and director. The result was magic. Ìfé was an all-time great. We gave people something they didn’t even know they needed — a breath of fresh air in a toxic cultural atmosphere.

The film was released in 2020, right in the thick of the pandemic. It was a true labour of love, but even I didn’t expect the scale of success it would achieve. Ìfé quickly gained international attention, won awards at home and abroad, and screened at over 25 film festivals around the world. And it’s still screening to this day.

And yet, the landscape hasn’t shifted as much as you’d think. Most of Nollywood still avoids queer stories. The SSMPA makes it virtually impossible to show queer films in Nigerian cinemas. So indie filmmakers and LGBTQ+ organisations remain the backbone of queer Nigerian cinema.

Since Ìfé, more films have joined the movement: Country Love (2022) by Wapah Ezeigwe, and All the Colours of the World Are Between Black and White, directed by Babatunde Apalowo, are some recent examples. But again, these are all stories about gay men.

Where are the lesbians? Where are the queer women?

That gap is exactly why I’m now working on the sequel to Ìfé, currently in post-production and set to be released in 2025. We’re not done telling our stories. We’re just getting started.

Queer people are still heavily underrepresented in Nollywood. When we do show up, we’re often caricatures — comedic relief, villains, or invisible altogether. But independent creators are pushing back. We’re using YouTube, private screenings, streaming platforms, and festivals to tell our stories on our own terms. The audience is ready. The demand is real. It’s the gatekeepers who are slow to catch up.

I didn’t set out to be a filmmaker. I didn’t plan to be an activist. I just wanted to tell the truth, because I know what it feels like to grow up in silence. To watch every film, every show, and never see yourself. To wonder if your love is real. To wonder if you even exist.

My hope is that the next generation of queer Nigerians won’t have to unlearn as much as we did. That they’ll grow up seeing queer love on screen, hearing queer voices in the media, and knowing — without doubt — that they are not alone, and they are not un-African.

And if our films can be a part of making that happen? Then that’s more than enough.

Pamela Adie is a public speaker and filmmaker. Her 2020 film, Ìfé, is the first full-fledged lesbian movie in Nollywood history.

Click here to see what people are saying about this story on social media.