By Ayodele Adio

Lawmakers in the House of Representatives are trying to use their oversight powers to override a law which protects Nigerian users from exploitative digital lending platforms, and it’s as alarming as it’s embarrassing.

What’s going on?

Over the years, digital lending platforms in Nigeria have generally operated without regulation, and their users have suffered for it. In Nigeria, it is not uncommon to have a loan app threaten your life, post your photo on the internet with embarrassing captions about the debt you owe or spam your contacts with messages warning you to pay up. From data privacy violations, threats, to dubious interest rates, digital lenders have violated Nigerian users in so many ways.

In July 2025, the Federal Competition and Consumer Protection Commission (FCCPC) enacted the Digital, Electronic, Online or Non-Traditional Consumer Lending Regulations, 2025 (DEON Regulations), to keep digital lenders in check.

The enactment of the DEON regulation meant that digital lending companies (loan apps and the like) have to comply and register with the FCCPC in order to avoid sanctions. The commission duly gave a January 5 deadline for this.

But on December 18, 2025, the Chairman of the Special Ad-Hoc Committee on Overlapping Jurisdictions, Procedural Gaps and Investor Concerns wrote a letter telling stakeholders and regulators to ignore the DEON Regulations in the meantime. The House of Representatives is doing this under the cover of its oversight privileges, but this is not what oversight entails. The House, in addition to lawmaking, is saddled with the responsibility of safeguarding the rule of law through principled, impartial oversight. But nothing about this its recent conduct signals that.

In addition to encouraging stakeholders in the digital lending industry to ignore the DEON regulations, the House of Representatives refused the FCCPC an opportunity to be heard during an investigative session held on December 15, 2025. This implies that the House had already drawn its own conclusions and was going ahead with it.

The House must understand that oversight is not a licence to substitute opinion for law. It is not a mechanism for suspending valid regulations by committee correspondence, and it is certainly not a platform for conferring informal exemptions on powerful market actors.

Why is this wrong?

Presently, about 453 companies have fully complied and have gotten full approval from the FCCPC, 35 have gotten conditional approval, while 103 have not complied. By disregarding the law and telling the industry that the DEON Regulations could be ignored, the House inadvertently handed undue advantage to dominant telecommunications companies and their lending partners. Smaller operators who have invested in compliance were left exposed, while powerful incumbents gained regulatory cover to continue business as usual. This is not market fairness; it is distortion sanctioned by silence.

When Parliament appears to side—intentionally or otherwise—with entrenched market power, it weakens Nigeria’s competition framework and undermines consumer protection. It also sends a chilling signal to regulators tasked with enforcing the law: that their authority is provisional, subject to political pressure rather than statutory mandate. No serious regulatory system can survive under such conditions.

Where do we go from here?

Members of the House must ask themselves a hard question. Is oversight being exercised in the public interest, or has it drifted into accommodation of influence? Is Parliament protecting consumers and the integrity of the market, or enabling regulatory arbitrage by the most powerful actors in the economy? History is unkind to legislatures that blur this line.

Nigeria’s digital economy depends on strong institutions that respect boundaries. Regulators must regulate. Courts must adjudicate. Legislators must legislate and oversee—without usurping executive or judicial functions. When these roles are confused, the rule of law becomes negotiable, and governance loses credibility.

What now?

The House of Representatives still has an opportunity to correct course. By reaffirming the enforceability of duly issued regulations, clarifying the limits of committee authority, and recommitting to fair, neutral oversight, it can restore confidence in parliamentary governance. Doing so would not weaken the House; it would strengthen it.

The alternative—allowing informal actions to erode lawful regulation while powerful corporations benefit—risks turning oversight into complicity. That is a legacy no responsible legislature should accept.

While it will be noble for the House of Reps to do the right thing, it will be sumptuous for Nigerians to do nothing. We owe it as a duty to ourselves to call lawmakers to order when they’re defaulting on the law and their responsibilities. With one voice, we must call them to order now and demand that they not interfere with the enforcement of the DEON regulations.

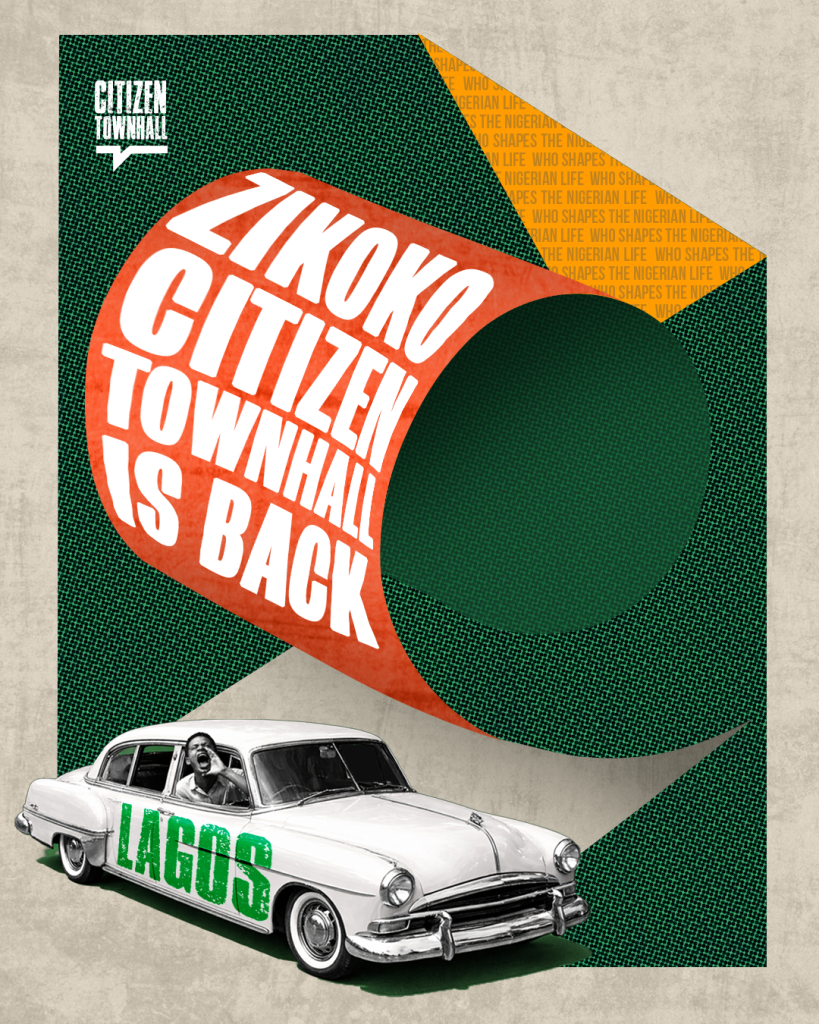

Young voices, big ideas, and the future of Nigeria all in one room. The Citizen Townhall is a flagship event by Zikoko where changemakers, experts, and everyday Nigerians will gather in Lagos to ask the hard questions: Who really decides our lives? What happens when we stay silent? And how powerful is our vote?

Don’t just read about politics when you can be part of it. Stay tuned for how to register.

We want to hear about your personal experiences that reflect how politics or public systems affect daily life in Nigeria. Share your story with us here—we’d love to hear from you!