When Ayobami Akinrinade handed a boy a notebook she had spent her own money producing, she expected curiosity. Instead, he tore out the page showing the male reproductive system and threw it away. She remembers sitting in the school office, stunned and close to tears. The boy, she later learnt, said he couldn’t bear to see the anatomy laid out like that.

“That moment hurt,” Ayobami told me. “It wasn’t just about the money. It was that a child would rather destroy information about his own body than face it. That showed me, again, how wide the gap is between what young people need and what adults think they should know.”

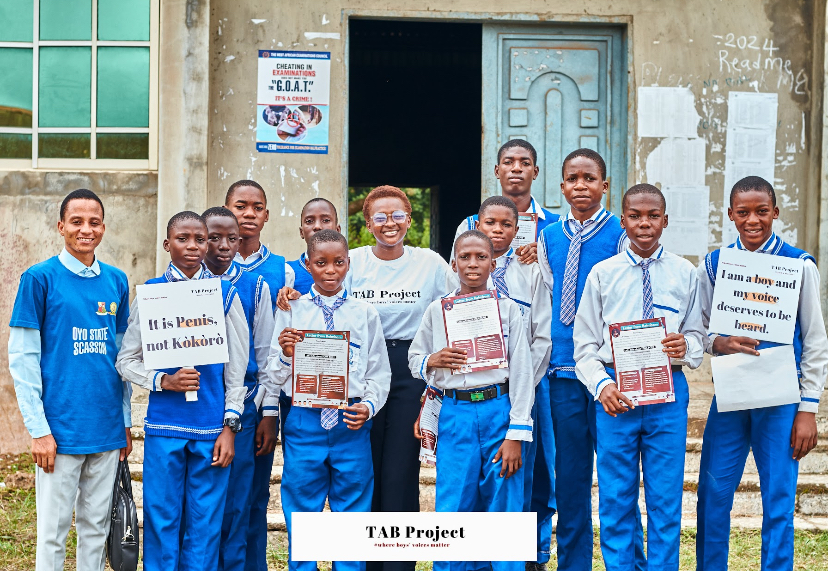

Ayobami runs two interlocking initiatives, Sex Education with Balmbam and Teach A Boy Child (TAB), both designed to deliver age-appropriate, factual Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights (SRHR) education to adolescents across Lagos and beyond. Her work ranges from school workshops to an active WhatsApp community.

What sets Ayobami’s work apart, though, is how she brings faith into the conversation. A committed Christian, she works closely with churches and faith leaders to teach young people about sexual health through a moral and spiritual lens, one that promotes abstinence while also providing factual, science-based education about their bodies. “I always tell parents and pastors that knowledge doesn’t corrupt,” she said. “It empowers. You can teach abstinence and still teach sex.”

The mission is simple: to educate on sex, make space for questions about consent and abuse, and bring boys into conversations that often focus only on girls.

What is SRHR? It means that every adolescent has the right to accurate information, bodily autonomy, safe relationships, access to reproductive health services, and the freedom to decide about their sexual and reproductive life, without coercion, discrimination, or violence.

And the World Health Organization (WHO) defines sexual and reproductive health as “… that people are able to have satisfying and safe sex lives, to have healthy pregnancies and births, and decide if, when and how often to have children. Access to sexual and reproductive health services is a human right.”

Despite growing awareness about sexual and reproductive health, access remains low among Nigerian adolescents. A 2020 study found that only 38.2% of young people in Enugu State, Nigeria, aged 12 to 22 had never used sexual and reproductive health services, highlighting the deep gaps in information, stigma, and access.

Why Faith, and how ‘Sex Education with Balmbam’ bridges it

Ayobami’s own life is the engine behind her work. She disclosed that she was sexually abused from childhood into adolescence — an experience that drove her to study sex education, secure scholarships for international certification, and build programs that speak directly to the needs she once faced.

That background also shaped an approach that deliberately engages religious communities. Many Christian parents and leaders, she says, view frank conversations about sex as a threat to morality. During a university class, she remembered, a fellow Christian student actually covered her ears and began to pray aloud when sex was being discussed.

“Christian communities have demonised sex so much that married couples sometimes struggle physically and emotionally,” Ayobami said. “Teaching sex or pleasure is not anti-spiritual. I tell church groups up front: I will use the proper words. If you can’t accept that, I can’t teach here.”

Her faith-forward framing, a project called Sex-gelism (Sex + Evangelism), aims to reconcile Christian belief with comprehensive SRHR. It helps her enter spaces many sex educators cannot. She insists on clarity rather than euphemism: “I don’t call their body parts by silly names. It’s the penis, vagina, vulva, and breast. Language matters.”

Cultural barriers: parents, protocols and silence

Across Lagos, she said, parents are the primary barrier. In one recent outreach, a boy confessed he had been punished and labeled “demonic” after his parents discovered he had watched pornography. Rather than guiding him, the adults had punished and shamed him.

“Parents demonised the child,” Ayobami said. “They see exposure as sin, not an opportunity to educate. We must involve parents before we teach children. When parents understand what will be taught, they usually relax.”

Teachers and school staff are often more receptive than religious leaders, Ada, a teacher who worked with Ayobami on the TAB project, said. Ada described how the project delivered lesson plans and educational materials that filled gaps schools were not equipped to cover. But she also warned of resistance in mixed-gender classrooms, cultural and religious pushback from parents, and a lack of training and resources for staff.

There are institutional hurdles, too. Ayobami said public schools are often inaccessible because of bureaucracy: “Go to the ministry, they give you a date that doesn’t work. It’s easier to work with private schools.” That administrative inertia, coupled with the absence of government sponsorship, forces many small NGOs to rely on community, family, and modest donor support.

Solutions in practice: WhatsApp, peer education and teacher training

Ayobami’s methods are deliberately practical and youth-centred. She prioritises age-appropriateness: educators confirm age ranges before sessions and tailor content accordingly. She runs peer education and WhatsApp groups where adolescents can ask questions privately and maintain anonymity; she mentors volunteers who then deliver classroom sessions and community events, like a mini-conference held for the International Day of the Girl Child in partnership with a local brand.

Favour, a volunteer, described her experience: she joined Ayobami’s WhatsApp community, volunteered at school outreach events, and saw the immediate uptake among girls. “The school proprietor said they had never had anything like this. The girls were so receptive,” she said.

The work also includes counselling and healing sessions for survivors. Ayobami recounted a camper who reported attempted molestation after a festival; the girl resisted further harm, a response Ayobami credits in part to earlier education on body autonomy and consent. She has also worked with adults recovering from sexual pleasure after trauma and men who seek redemption after offending.

Ayobami estimates she has reached over 2,000 young people and worked with more than 20 schools, and her WhatsApp community has over 1,000 members. She partners with national and local organisations, including Change Is Female, Smiley Foundation, and Teach for Nigeria fellows, but stresses the need for government recognition and funding.

“If I had ₦50–₦100 million, I could roll TAB out across Nigeria and into other African countries,” she said. “Policy implementation is crucial. SRHR is often treated as a girls-only issue. Boys must be included. Also, we need young trainers; old methods don’t work with today’s adolescents.”

She also named a persistent problem: capacity. Small NGOs are often run by a handful of exhausted founders who need professional staff and reliable funding. And public institutions rarely fund grassroots sex education initiatives, leaving critical work under-resourced and fragmented.

From the interviews, it’s clear that practical, respectful engagement works. Teachers who co-design lessons, parents briefed in advance, faith-based framing that does not denigrate religion, age-appropriate modules, and safe digital spaces all reduce resistance. Peer testimony, girls and boys sharing what they learned, helps normalise SRHR education.

But systemic change is needed. Ayobami and the educators want three policy shifts:

- Integrate comprehensive SRHR into the school curriculum, not as an optional add-on but as a standard subject.

- Fund and professionalise grassroots organisations so they can hire staff and scale.

- Ensure boys are explicitly included in national SRHR guidelines and programmes.

Hope?

Back in that school office, after the boy tore out the page, Ayobami did not give up. She redesigned the workbook, worked with teachers to prepare students emotionally and built a WhatsApp forum where questions could be asked privately. Months later, the same school invited her back.

“We’re not solving everything,” she says. “But every time a child knows the name of their body part, knows consent, knows who to tell if something happens — that’s a life changed. That is what keeps me going.”

This story is made possible with support from Nigeria Health Watch as part of the Solutions Journalism Africa Initiative.