Musa Garba*, 59, joined the Nigerian Army in 1988 at age 22, hoping to build a life of meaning and stability. He spent over thirty years in service, rising from a junior airman to Squadron Leader.

His first salary was ₦400. When he retired in 2019, he received ₦15 million in gratuity and a ₦200k monthly pension. But within a year, the money was all gone.

In this story, he breaks down how his salary grew, what retirement gave him, and what a lifetime in the military truly cost.

This is Musa Garba’s story, as told to Aisha Bello

I was the oldest of five children, the only boy in a house that suddenly felt too quiet after my father died in 1979, when I was twelve. By 1986, at 20, I’d finished secondary school with two paths before me: sell Peugeot spare parts or find something bigger than myself.

The spare parts business felt like surrender. It was an Igbo man’s trade, and only a few people from my tribe, in the North, made it work. The older relatives who suggested it meant well, but they were really asking: Who else will pay for your dreams?

It was one of those hot afternoons in 1987. I was running an errand at the motor park when I saw a Nigerian Air Force recruitment poster on a wooden board near the ticket stand.

That same week, I ran into an old schoolmate who had joined two years earlier. He had come home in uniform, boots polished, posture straight, and people calling him Officer. He told me they were recruiting again soon and that all I needed was my WAEC and some guts.

The Air Force offered something different: purpose, education, and a chance to become someone important. While university remained a far-fetched idea, the military remained an open door. Once I’d earned my place, I could fight to the top.

So I chose the uniform over the spare parts.

My First Salary Was ₦400

In 1987, I decided to join the Air Force. I had ₦20, which was only enough to buy the form, so I trekked most of the way to the Air Force base and joined hundreds of young boys already queuing under the hot sun.

We went through every test, physical, medical, and mental. After two gruelling weeks of screening, I ranked in the top five for my region.

Then, we were off to a military base for basic training, where we drilled, marched, and trained for six months straight.

At 22, I was officially an Airman, posted to Bauchi.

My starting salary was ₦400; by 1990, it jumped to ₦700.

Then Abacha toppled the Babangida government, raising our salaries to ₦3,000 in 1993.

Still, I remained at the bottom of the ladder — an Aircraftman, the lowest rank in the Air Force. It wasn’t enough for me. I wanted the salute, respect and prestige.

I Wanted More

The Nigerian Air Force has two main career paths: non-commissioned and commissioned.

I started at the bottom — a non-commissioned airman, straight out of basic training. The highest you can go is becoming an Air Warrant Officer. But the path upward is painfully slow, especially without someone pushing your name or pulling strings.

We do the grunt work: patrol duty, maintenance, logistics, field drills, even guarding officers’ homes. But it came with fewer perks, less power, and even less money.

The commissioned route is different. That’s where the leaders are made. You either spend five years at the Nigerian Defence Academy (NDA) or join through the Direct Short Service Commission (DSSC) if you have a diploma or degree. After six months of officer training, you’d be commissioned as a Pilot Officer. From there, your career can climb to Air Marshal if you play your cards right.

They get the bigger salaries, better housing, promotions, and prestige. That was the life I wanted.

But I didn’t have a diploma or a degree.

By 1995, I still hadn’t moved a rank. Meanwhile, younger airmen, with school certificates or backers, were climbing up fast. That was when I knew I had to switch up the game.

I enrolled in a part-time ND programme and paid every kobo from my salary. I got my diploma in 1997, applied for the Short Service course, took the exams, and passed.

By 1998, I was commissioned as a Pilot Officer, and my salary jumped to ₦10,500. More importantly, I was saluted for the first time in my life.

Back in my base, life was finally starting to feel stable. I had started a family: a wife, two children, a steady posting, and a future that looked like it might finally live up to the dream.

Or so I thought.

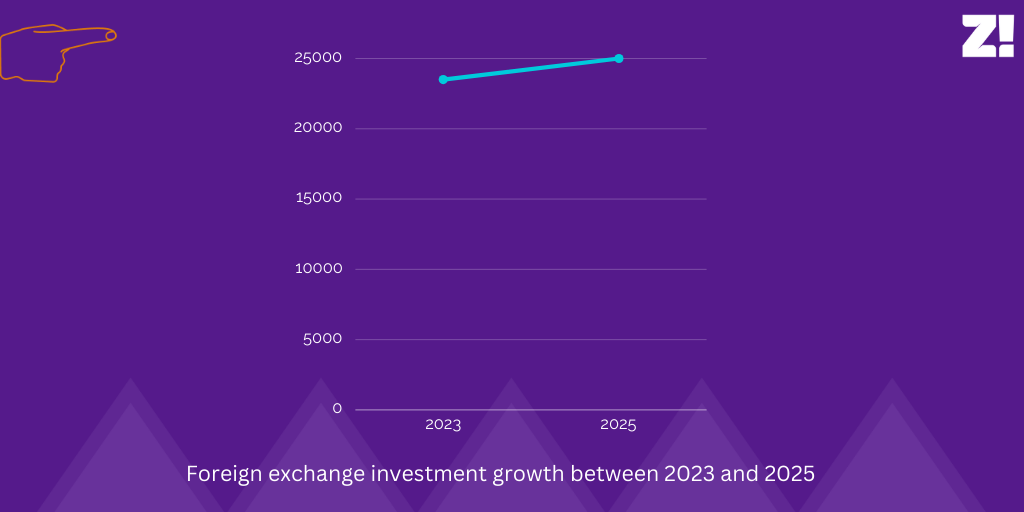

Join 1,000+ Nigerians, finance experts and industry leaders at The Naira Life Conference by Zikoko for a day of real, raw conversations about money and financial freedom. Click here to buy a ticket and secure your spot at the money event of the year, where you’ll get the practical tools to 10x your income, network with the biggest players in your industry, and level up in your career and business.

Career Growth Before Retirement

After I was commissioned in 1998, I was posted to another state, and by 2001, my name finally appeared on the promotion list for Flying Officer. I wrote the exam, passed, and my salary jumped to ₦31,000. It was the first real financial sign that I was moving up.

In those years, I learned what it meant to lead. I wasn’t just receiving orders; I was briefing airmen, coordinating missions, and working closely with ground troops to plan aerial support.

In 2006, Obasanjo’s second administration reviewed our salaries, and mine rose to ₦71,000.

By 2009, I was promoted to Flight Lieutenant and earned about ₦100,000, the standard pay for that rank.

In 2012, I climbed up to Squadron Leader, and my salary rose slightly above ₦200k. But that was the last promotion I ever got.

I kept writing the exams, year after year, but nothing changed. It was clear: my career in the Air Force had run its course.

By 2021, I was served a letter of voluntary retirement. At 55, I had hit the official retirement age.

I Retired From the Air Force with ₦15 Million. It Was Gone in a Year.

When I retired, I was paid ₦15 million in gratuity.

I moved my family back home, where it all began. After three decades of service, all I had to my name was a property I’d bought years ago. I spent every kobo raising it from a shell to a finished house.

I paid off the kids’ tuition, refurbished the house, installed solar panels, and tried to piece together a life, but the money was gone within a year.

Now, I live on a ₦200k monthly pension. It covers the basics for now. But how long will it last? Ten years? Twenty? My youngest is just 16. There’s still a long road ahead.

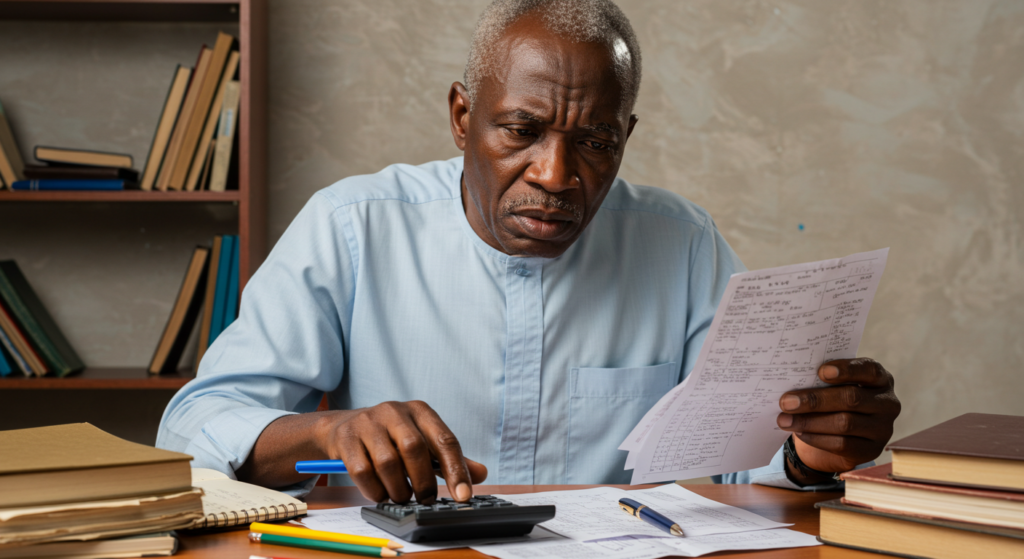

If I could go back to when I first got that ₦15 million, with a clear head, I would’ve invested a good chunk in farming. Now, starting a farm isn’t cheap, but I try.

Most days, I’m out there, cutlass in hand, tending a small garden behind the house.

I’ve served. I’ve seen war. I’ve seen death. Now, I’m just trying to live.

*Editor’s note: At the subject’s request, his name and certain details of his active-service years have been withheld to protect his anonymity.

Also Read: The Nigerian Air Force Is Recruiting. Here’s Everything You Need to Know

[ad]