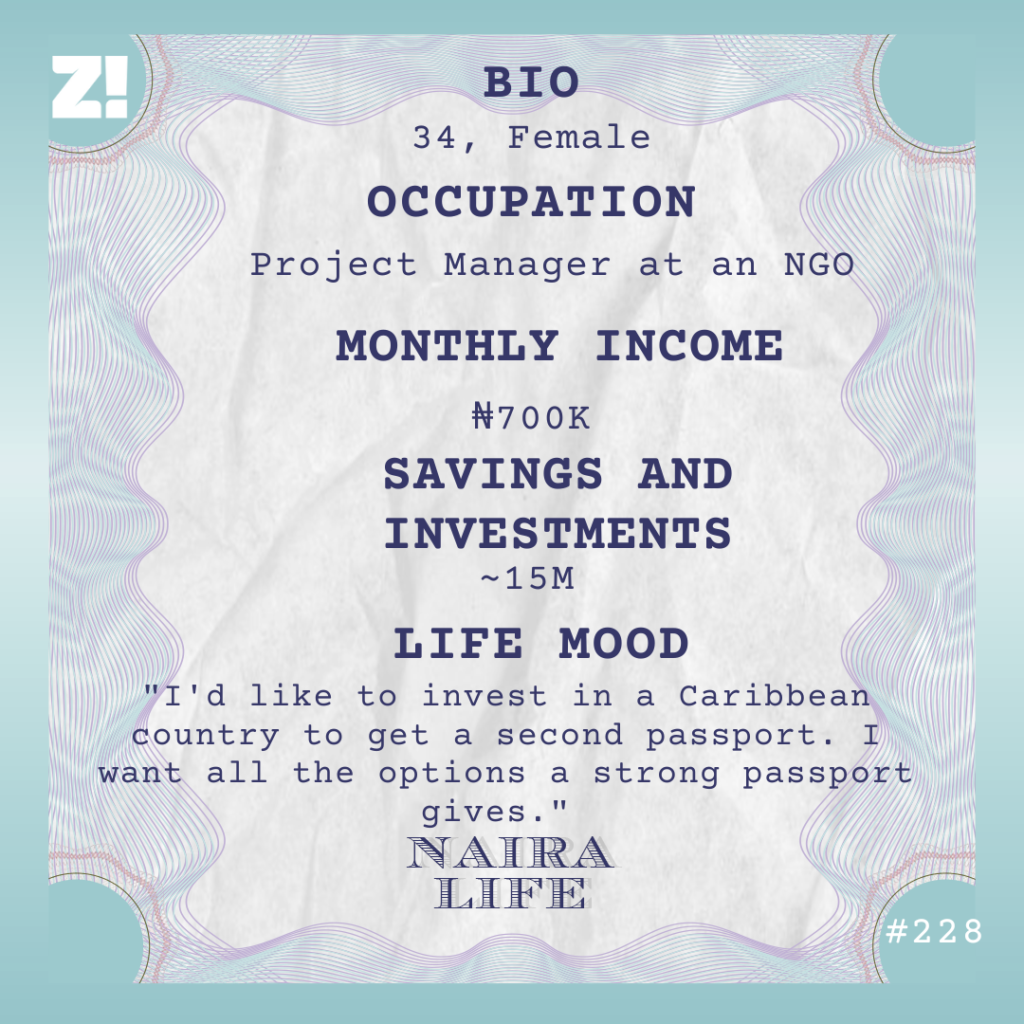

Every week, Zikoko seeks to understand how people move the Naira in and out of their lives. Some stories will be struggle-ish, others will be bougie. All the time, it’ll be revealing

Tell me about your first significant memory of money

When I was 10 years old, my mum came home one evening and called me and my four siblings into her room. Then she started handing us cash, and we got different amounts according to age. When we asked her what it was for, she said it was our allowance. This was a first.

Until that moment, I didn’t know you could be given money for the sake of it. Previously, I’d only gotten money when I was sent on errands. The ₦50 I got was the first money I could call my own.

This event was even more striking because of our circumstances.

What circumstances?

Our financial situation was tough. I don’t remember a time the family was 100% comfortable. There was always a struggle — from food in the house to school fees. We even got new clothes only at Christmas.

And it wasn’t even like my parents weren’t working. My mum was a chef and worked in the kitchens at hotels, and she also sold pastries on the side. My dad was a civil servant. Well, until he lost his job in 2004.

What happened?

He had an issue in the office and was sacked. Sadly, he was close to retirement and lost all his benefits when this happened. But he wasn’t going to go out without a fight, especially because he believed he was wronged. He thought the judicial system would clear him, so he pursued the case in court with everything he had, which was our limited resources. As I’m talking to you right now, the case is still ongoing.

Since 2004?

Yes, since 2004.

Now we were a single-income family, and everything went downhill. I was in JSS 3 in a federal government secondary school, and my mum almost pulled me out.

Also, we had to move from the staff quarters when my dad lost his job. First, we moved to a BQ the post office owned. Then they chased us out of that one, too. Like that, we moved from the GRA to a rough part of town.

It must have been tough. Did your parents have conversations about money with you?

My mum kept us up to speed. She had a way of making us understand whatever the situation was. In addition, she told us details of her job — where the money came from. We knew when she got a better-paying job or the one time she lost out on a job that’d have been very good for us.

My mum also involved us in her pastry business. My siblings and I learned very early how to bake. Whenever she wasn’t available, we managed the business. I was in boarding school through secondary school, and I did this whenever I was home for the holidays.

Was this the first thing you did for money?

In a way, yes. The money I made was for my mum and the family though. I made money for myself for the first time after secondary school in 2009.

My best friend said I could come to work at her mum’s school. Her mum was also excited to have me because I was very articulate. I was assigned to the Nursery 3 class, and my salary was ₦4500. I was there for eight months and left after I got an admission offer at a university in the southeast.

What happened next?

I was back to having no job and no income. And there was still an unavailability of cash at home. My upkeep was ₦4k.

Per month?

Haha. No, per semester. At the beginning of each semester, I’d carry as many groceries as I could carry from my mum’s store — she had retired from catering and opened a groceries store — and 10 litres of kerosene to school. Then figure out how to live on ₦4k for three months.

My final year was a bit better. My oldest sister got a job and started sending me money now and then. It was the first time I could boast of having up to ₦10k at the beginning of the semester.

I felt like a big girl until one day, one of my friends was complaining about being broke. I thought we were in the same struggle until we stopped by the ATM. Ask me how much this babe had in her account.

How much?

₦60k.

“Broke” for me was having ₦500 in my account and praying to god that the ATM would dispense ₦500 notes. Every time this happened, I went home thinking that a miracle had happened.

One of the reasons I survived university was because I had a lot of privileged friends, and I didn’t always mind when they offered help. For the most part, though, every day was a struggle to get by. But I did it and graduated in 2013.

How did it go after uni?

I moved back home. However, I wasn’t just going back to help with my mum’s business. So I hit the mall in the city looking for jobs, and I found one in a fast-food restaurant. My salary was ₦20k.

Do you remember how it felt the first time you got paid?

The first thing I thought was that I was now earning in one month what I got in four semesters in uni. That said, it didn’t feel particularly satisfying. Although I was broke in uni, I was surrounded by people who had money and knew how to spend it.

It wasn’t like I didn’t acknowledge that my pay was something. I could now buy a few things for the house and even save, even though there wasn’t a process to it. I just tried to save something every month. This ended when I got sacked after eight months.

Sorry?

I worked at the cashpoint, the management gave us ₦7k every morning. They called it a “float”, and it was what we used as change. At the end of the business day, you must have ₦7k on top of whatever you sold that day. And the policy was that the allowable excess or shortage shouldn’t be more than ₦25.

On the day I was let go, I was the only cashier on duty and it was rush hour on a public holiday. It got overwhelming, and I started taking orders without punching them into the system. When everything settled, I went back and logged everything I sold. But I forgot a cup of ice cream for ₦400. So I had an excess of ₦400 in my sheet.

The manager called me in to explain, and I did. I thought that’d be the end of it because I gave so much to that job. I was also their best cashier. Like a joke, he asked me to submit my uniform and badge and leave the premises.

I was more annoyed than anything else. I missed my convocation for these people, and I was let go because of ₦400 that I didn’t even steal.

Bruh. I’m sorry

I was embarrassed, and it took me one month before I told my parents that I lost my job. But at least, I saved some money from the job, and it was enough to finish my final clearance in school and go for NYSC.

NYSC was the first time I touched proper money.

How?

My PPA was the local government council, and working there gave me access to information. The council was NGO’s first stop when they were looking for corps members to sign up for field studies. Because of this, I worked with three NGOs during the year and helped them conduct their studies. I got ₦200k from the first NGO for one month of work. The second and third paid about ₦300k each, and they both lasted for one month.

Interesting

This is how payments worked: you got something called per diem every day you were out on the field. The sum accumulates into a lump sum, which you receive at the end of the project.

So I got about ₦800k from this alone. But it also gave me some experience in the development sector. This got me into the sector eventually.

Oh yeah? Let’s talk about that

When NYSC finished in 2015, I hoped to get a job in the local government where I served, but it didn’t happen. I returned home, and nothing happened there, too.

In February 2016, a supervisor I’d worked with sent me a job opening at an NGO, and I applied. He also recommended me to the programme manager. At the end of the process, I was hired as an ad-hoc staff for a data entry role. The pay was ₦23,500.

I was at the job until March 2017.

Why did you leave?

The funding ran out. But it wasn’t the end — another position opened up in the organisation funding the project, and I also applied to this. Unfortunately, I missed the interview. Two months later, they miraculously invited me to interview for another role in the north-central. I was in a city in the south-south to interview for a rubbish job I wasn’t sure about.

When I saw the invitation to interview, I hit the road again and spent 12 hours before I got to the city. Thankfully, my oldest sibling — a brother — had gotten married and my sister-in-law was living in the city. I went for the first interview, then three more interviews and a test. I left with a job.

Yayy

I still remember how time froze when I got the call. My salary was ₦150k.

But you had to move to a new city

I stayed with my sister-in-law for about five months when I moved, and transportation was my major expense. I wasn’t paying rent or buying a lot of food, so I could save some money. My running cost during this time was ₦80k, and I was saving ₦70k/month. That’s how I raised money for rent — I got a self-contained apartment for ₦400k/year and moved there in October 2017.

How was it going at work?

After one year and eight months and a review that increased my salary to ₦250k/month, the project ended. Two months later, I found another job that paid me ₦350k, but the project also closed out after four months.

Heh. What’s going on?

Jobs in the development sector are subject to funding, and they also have timelines. If the project is renewed, fine. But if it’s not, the project closes and the staff is back in the labour market.

A lot of networking goes on in the sector, too. That’s how you get really good jobs. For example, my next job wasn’t advertised publicly, and I only knew about it through someone I’d worked with. This job changed a lot for me.

How so?

It paid in pounds.

Say no more. How much though?

£1k as a project support manager.

I started the job in July 2019, and the exchange rate was between ₦600 and ₦800 in the one and half years I spent there.

The most important thing the job helped me do was to migrate my savings from Naira to Pounds. I’d change £400 to naira and live on it until it ran out. Also, the naira savings I had before the job became my expense account, giving me little reason to touch my pounds.

When the project closed out and I left the job in April 2021, my naira account was completely obliterated. But my pounds savings were a little significant.

How much did you have in it?

About £12k.

I stan

I was back on the streets, though. And it took five months before I found a new job.

How did those five months go?

It was a mix of different emotions. First, I wasn’t bothered. I needed to rest, so I was chilling with my friends who were also affected. The feeling of dread started creeping up in the second month. By the third month, we had found a library we went to every day to apply for jobs. In the fourth month, we were getting a bit desperate and were reaching out to everyone we knew.

I eventually got an offer in August 2021 and resumed the role in September. My starting salary was ₦600k gross and ₦470k net. If I didn’t have a five-month gap in my resume, I’m sure I’d have had the leverage to negotiate more.

The game is the game

But I’ve gotten two raises in the past two years. Now, my gross salary is ₦800k and the net is ₦700k. My net salary would have been lower, but I’m paying less tax because of the way my salary is structured. It’s been a big game-changer.

Explain, please

There’s a life insurance policy scheme at my place of work, and what you put into it goes there before tax. So the more money you dedicate to the insurance fund, the less tax that’s deducted from your salary.

What does this look like in practice?

The last tax I paid before I joined the life policy scheme was ₦105k. At the time, my gross salary was ₦600k. When I got a raise and my gross increased to ₦700k, I started putting ₦300k into the policy every month, and my tax reduced to ₦56k. Now that my gross salary is ₦800k, I put ₦400k into the insurance policy, and I only pay tax on the remaining ₦400k.

At the moment, I pay ₦57k in tax plus an extra ₦43k in other deductibles and take ₦300k home every month. If I wasn’t putting money into the life insurance scheme, my tax alone would have been ₦120k.

This is very interesting. But what happens to the money you put in the insurance scheme?

I can liquidate it after three months. But if I don’t touch it for a year, I get a 4% return on everything I put in. Last year, I did ₦300k/month for a year and got ₦3.6m + ₦144k at the end of the year.

This is my primary savings account now. And I’m motivated by the fact that it allows me to have a disciplined savings plan outside of my net income. However, there is a caveat.

I’m listening

The insurance company is only liable to pay my family ₦1m if anything happens to me, no matter how much I have saved in it.

But you know what? I weighed everything and decided that the pros outweigh the cons. At the end of this year, I’m going to have ₦4.8m in savings.

Also, I’m in a contribution scheme at work with nine other people. Everyone puts in ₦150k/month and someone packs ₦1.5m each month. This is money for my rent, which is now ₦1.2m. The extra goes into my secondary naira savings account.

Wait, this means you currently live on ₦150k a month?

I mostly live on ₦100k/month — I send ₦50k home to my family. I won’t lie, it takes a lot of discipline to do this, but I’ve built that muscle.

Omo. Let’s break it down, please

Other expenses come every three months — I buy food in bulk and spend ₦100k on that. Also, I take my dog to the vet and spend about ₦25k. Mostly, I just borrow money from my naira savings account to do this and figure out a way to return it later.

Also, the money I send home monthly is for my parent’s basic upkeep and doesn’t accurately capture what I spend on the home front. I’m the highest earner in the family and as a result, I contribute the most financially. Recently, I paid my parent’s rent, which was ₦192k. I’m mostly responsible for healthcare and other expenses too. I fund these from my savings.

How much money do you have saved up now?

Life insurance policy — ₦2.4m

Pounds savings — £10k

Naira savings — ₦90k

Any extra money that comes in — mostly cash gifts from senior colleagues and friends — goes into my naira savings account. I’d have had more money there, but I just took ₦1.5m to buy two plots of land.

If you were wondering what I did with the ₦3.6m I took out of the life insurance scheme last year, I also used it to buy plots of land.

I have an approach to these land investments.

Let’s hear it

I look out for distress sales and buy cheap. It’s my strategy to maximise my capital in these investments. So the landed properties I currently have are valued higher than what I paid for them.

You’ve come a long way. What does financial freedom mean to you?

It means I’m at a place where I’m not an incident away from going back to square one. I acknowledge my growth, but sometimes, I’m like, “Is this enough?”

As it stands, I don’t have enough safety nets that’ll protect me from whatever life throws at me. It’ll feel like I’m financially free when I build those.

In the present, what do you want but can’t afford?

Investing in a Caribbean country and getting their passport. I want the options a strong passport gives you. If I manage to do that, I’ll feel like I’ve arrived.

What’s your financial happiness on a scale of 1-10?

This time last year, it was a 7. But there is lots of uncertainty in the country now and the prices of everything have gone up. It feels like I’ve been broke all year, and I may have to revise my budget. I hate it. So right now, it’s a 5.

If you’re interested in talking about your Naira Life story, this is a good place to start.

Yes, I want to do a Naira Life

Find all the past Naira Life stories here.