Before my mother passed away, I thought I understood what it meant to be the eldest daughter: extra chores, keeping my younger siblings in line, and generally being more responsible. My immediate younger sisters were just a year and three years younger than me, so in some ways, we shared the load. But the day they told us she was gone, everything shifted. The adults said, “You have to be strong now. You’re the mother.”

At her funeral, I wasn’t allowed to cry. Aunties and Uncles pressed my shoulders and whispered, “If you break down, what will your siblings do?” From then on, people stopped asking how I was and started asking, “How are the children?” as if they were mine. My mum’s best friend once pulled me aside to ask what would happen to our youngest, who was only five at the time, if I left the country for university. I was sixteen.

That was when I learned that being the eldest daughter wasn’t just about responsibility; it was about always being the one to swallow the difficult pill quietly.

Across Nigerian homes, the first daughter is often given a title before she even knows she has a choice. At birth, we are seen as ‘second mother’. We are Ada. Ìyá Kéjì. Adiaha. The name is different for each tribe, but the cultural role and expectations remain the same. We are caretakers, peacekeepers, and even guinea pigs, long before we understand what any of it will cost.

Globally, studies show that eldest daughters experience higher levels of anxiety, burnout, and guilt than their siblings (University of Bath study). In Nigeria, where caregiving is deeply gendered, that pressure often starts in childhood.

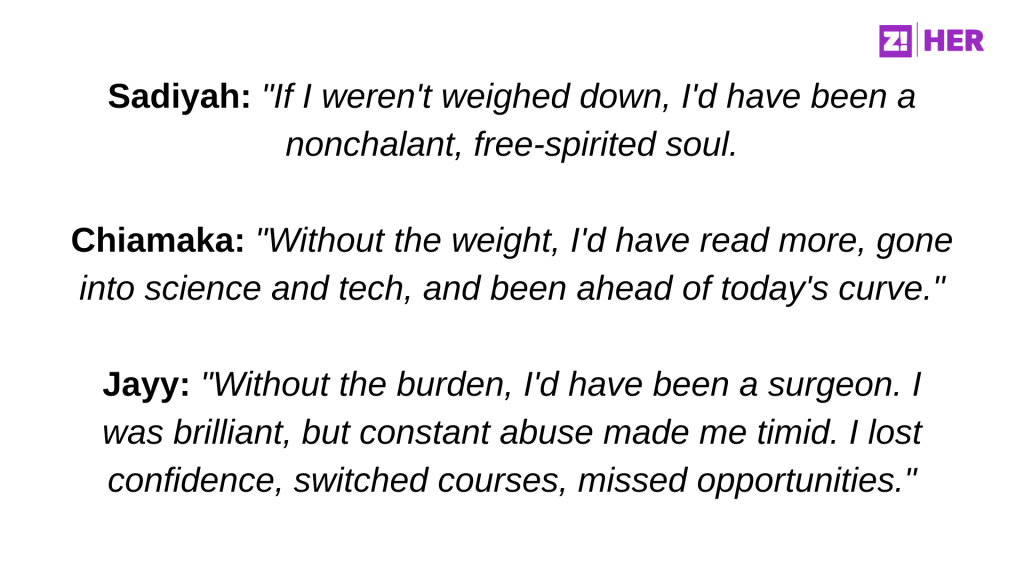

“Being the eldest daughter felt like being a lab rat: trial and error, but mostly error.” – Chiamaka, 22.

From a young age, we learn that to be loved by others, we must serve. That our worth is tied to how much we can carry. We manage chores, raise siblings, absorb our parents’ emotions, and hold the family together, very often at the cost of our own needs.

For 29-year-old Ernest from Abuja, she was automatically the second parent. “There were so many responsibilities and standards that I don’t think I even had formative years. I just became an adult overnight and never stopped.”

But increasingly, eldest daughters are breaking their silence. We’re no longer talking about exhaustion alone, but the resentment and rage that quickly follow. And beneath that rage: grief for the childhood many of us never had, and the women we were never allowed to become.

The Invisible Labour

The weight that first daughters carry starts early. Sometimes, before memory even forms.

When Godsgift was seven, she and her siblings were locked in their family’s face-me-I-face-you apartment while her parents were away. The banging on doors, the shouting, it was chaos. She had a baby sibling, not even a year old, crying from all the noise, and another sibling just as frightened as she was.

‘I don’t know how, but I remember acting like I was their mother and ignoring my own fears,’ she says, now 20.

That moment, a seven-year-old girl pushing down her terror to comfort others, is the eldest daughter’s experience refined to its purest form. You learn early that your fear comes second. That someone has to hold it together, and that someone is always you.

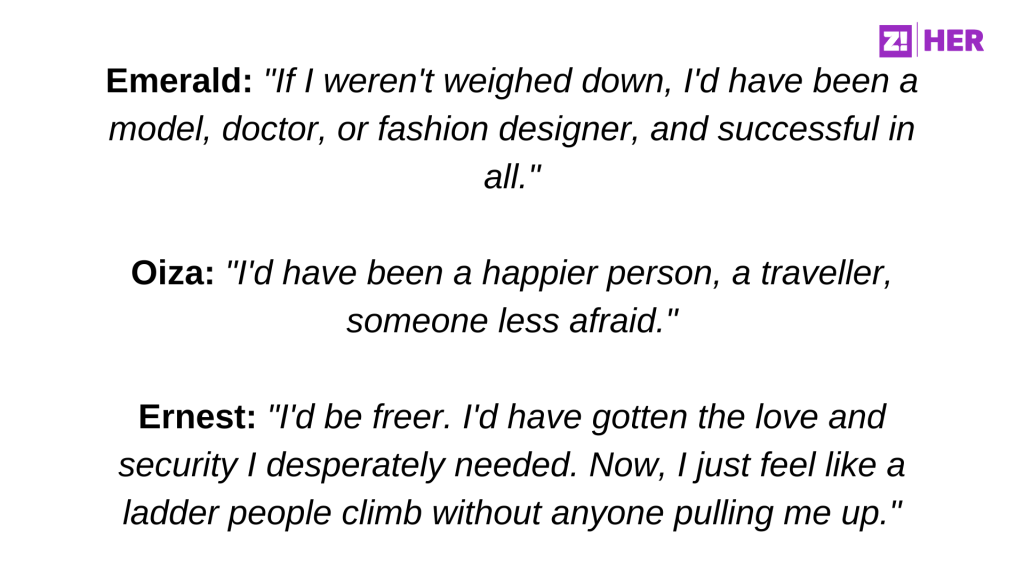

Oiza, 25, remembers it too: “It was so tiring. It’s like being the small mummy of the house. In our home, the girls were literally the slaves of the boys. We would be woken up earlier than they are, cook for them, and do almost everything for them. Yet anything that goes wrong, you get yelled at.”

Her words echo across other eldest daughters’ lives, like 25-year-old Dani, who says, “From day one, I had heavy responsibilities. I raised cousins as well as my siblings because I was also the first grandchild. I lost my identity in the process.”

The Perfectionism Trap

Over time, the pressure calcifies into something harder to name. Every choice is scrutinised, every action sets a precedent for everyone watching. And when you’re never allowed to fail, you stop trying to be good. You become obsessed with being perfect.

Sadiyah, 21, from Kaduna, knows this intimately. “I never had the chance to just be myself or do the things I loved, because my family always had to come first. Every decision I made was filtered through: ‘Will my parents be proud? Will my siblings still respect me?’ The pressure turned me into a toxic perfectionist; the typical ‘serious, perfect daughter.’”

“I sacrificed my childhood. Every action was branded ‘responsibility.’ It’s probably why I’m so reclusive now. I resent my family a lot, especially because my siblings get more grace than me. I was a serial bed wetter as a child, and my parents used that to vent their frustrations. I still remember my father beating me with a huge stick, calling me filth, telling me I’d live in shame forever.

My siblings now do the same things I was punished for, but they’re excused. Later, I found out bedwetting was hereditary. They knew. My mum was also a first daughter. She tells me how lucky I am that my father isn’t as abusive as hers was, but she trauma dumps on me the same way,” adds Chiamaka.

According to clinical psychologist and founder of Ndidi Mental Health Clinic, Amanda Iheme, this perfectionism is engineered through one of Nigerian parenting’s most effective weapons: guilt.

But for eldest daughters, the guilt is amplified tenfold. “Anything your siblings do is your fault,” Amanda explains. “You are the first child. You’re supposed to do this and that. There’s a lot of ‘you should have, you’re supposed to,’ and very negative experiences follow.

The conditioning is relentless. Nigerian parents, Amanda notes, struggle to manage their own emotions, so they project them onto their children, especially their first daughters. They make them responsible for everyone’s emotional state.

“When you are responsible for your parents’ emotions, responsible for your siblings’ emotions, responsible for the day-to-day operation in the house, you’re going to feel a sense of guilt that if you don’t do what you’re supposed to do, things are going to fall apart,” Amanda says.

“When your being is tied to responsibility, if you’re not responsible, you’re not going to feel worthy,” Amanda explains. “My worth is very much tied to my capacity to do this. So if I don’t do this, then who am I?”

That question—who am I without this burden?—haunts eldest daughters well into adulthood. And the burden only grows heavier.

What She Said: I’m the Eldest Daughter Who Chose Herself, and I Make No Apologies

Childhood conditioning is one thing, but adulthood is where the weight becomes unbearable. Now we’re paying black tax, pausing our own dreams, watching our bank accounts drain while our efforts go unacknowledged. Somewhere between the forgotten sacrifices and being taken for granted, something breaks.

The Financial Drain

For 25-year-old Oiza in Abuja, that breaking point came on an ordinary night: “I was sending money home while still in school. I even took loans and overdrafts just to cover bills. I remember restocking the house one day and still being told by my mum that all I’d achieved was giving her access to paid TV subscriptions. Something broke in me that night.”

The financial burden starts early and never really stops. Oiza’s story isn’t unique; it’s the norm.

Jayy, 30, remembers her NYSC year with bitter clarity. On a ₦19,800 monthly allowance, she made sure one sibling got into university. Later, earning less than ₦100,000, she somehow put two more siblings through school. When she mentions this now, her parents insist it was her duty. “My parents only sponsored three out of six of us to university. The rest were left as “my responsibility.”

For 25-year-old Blessing in Osun State, the pattern is suffocating. “I’ve had to sacrifice my money for the family’s financial issues. It’s like I’m working for them. The moment I don’t have, I get subtle insults. The moment I have, you are the most amazing child again. I’ve wanted skincare for years now, but have never been able to buy it because of this family.”

It’s not just the money. It is the way their own needs become luxuries they can’t afford. It’s wondering when, if ever, it will end.

Manuella*, 27, remembers being blamed for an ICT error during her sister’s school registration, something completely outside her control. Her sister humiliated her, exaggerated the story at home, and their mother called her wicked. “No apology came even after my dad discovered it wasn’t my fault.”

The cruelty isn’t always loud. Sometimes it’s quiet and insidious, the assumption that if something went wrong, the eldest daughter must have failed somehow.

The Snapping Point

Eventually, something has to give.

For 32-year-old Deborah in Ilorin, this year was that moment. “I snapped. I lashed out at my parents and cut them off. I only speak to my siblings now.”

Tife*, 23, in Lagos, carries a different kind of scar. When her younger sister stole money, everyone assumed it was her. She was punished for weeks until her sister finally confessed, years later. The apology never came, but the memory remains.

The resentment doesn’t just come from the sacrifices themselves. It comes from the invisibility, the way our efforts are forgotten, minimised, or worse, expected. It comes from being punished for things we didn’t do, blamed for outcomes we couldn’t control, and told we’re selfish the moment we hesitate to give more.

But here’s the question that haunts many of us: if we know this is destroying us, why can’t we just walk away?

“If your identity and your worth are built on your capacity to help, and someone is saying that you should drop that… It then says, Okay, if I’m not this person, if I’m not helping all these people, if I’m not saving all these, then who am I?” Amanda explains.

It’s not just about breaking a habit. It’s about confronting an existential question that has no easy answer.

And even when first daughters recognise the dysfunction, even when we see how much it’s costing us, we often return to the same patterns. Amanda says this isn’t a weakness, it’s human nature.

“We will always go back to what is familiar, even if it’s painful, because in familiarity we have control. In familiarity, we can predict what is about to happen.”

The guilt is familiar. The burden is predictable. Freedom? That’s terrifying.

And when you dig deeper, you find this isn’t just one generation’s story. It’s a cycle passed down like an heirloom no one asked for.

The Generational Cycle

Dani, 25, sees it clearly now: “I see the same cycle in my mum and grandma, what I call the ‘Messiah complex,’ the need to carry everyone’s burdens, even outsiders.”

Mother to Daughter

Oiza looks at her mother and sees her grandmother’s shadow. “She reminds me of my grandma, neglectful and manipulative, even though she once swore not to repeat those cycles.”

Chiamaka’s mother was also a first daughter. Instead of shielding her daughter from what she endured, she uses it as a measuring stick. “My mum was also a first daughter. She tells me how lucky I am that my father isn’t as abusive as hers was, but she trauma dumps on me the same way.”

The first daughter role doesn’t always go to the biological first daughter. Sometimes, it goes to whoever is willing or forced to carry it.

Emmanuella, technically the second daughter, stepped into the role when her older sister couldn’t. “My mum was also the second daughter who filled eldest duties, and she still carries her siblings’ burdens.” The weight doesn’t retire. It doesn’t age out. It just keeps going.

It’s presented as an honour. As duty. As what good daughters do. And so it continues.

The Darker Side: Abuse & Punishment

Chiamaka was a serial bedwetter as a child and was brutally punished for something she later learned was hereditary and that her parents knew.

Jayy carries a memory that still makes her voice shake. At nine years old, her mother rubbed ground pepper in her vagina as punishment. Her mother starved them often, always positioning herself as “God’s favourite” while destroying their childhood.

And then there’s Emerald*, 26, whose words are so incredibly sad: “I sacrificed my childhood, my virginity (I was raped coming back from work), my sanity, and what was left. If I could come back again, I’d never be an eldest daughter.”

Breaking the Cycle

The problem, Amanda explains, is that this burden isn’t seen as trauma; it’s seen as a “right of passage,” a thing of honour. “If we already have a whole system that celebrates that sense of responsibility… it would be very difficult.”

We’re talking about dismantling a cultural expectation woven into Nigerian families.

If change is going to happen, it has to start with parents. And the first thing they need to understand is this: “Your first children are not your assistant parents. They can support you with siblings, but it doesn’t have to be seen as a responsibility where the child feels like, ‘Mommy and daddy won’t love me if I’m not doing this.”

Amanda emphasises another critical point: “Just because your kid comes across as self-sufficient does not mean they’ve stopped being children. They still need someone to tuck them in at night. They still want to be hugged and told that they’re beautiful.”

The Path to Healing

So what about the eldest daughters living this reality right now? What does healing look like when you’re already in the thick of it?

Start Small

Amanda’s advice is simple: “Start small. Start taking care of yourself first and doing the self-awareness work to know yourself.”

She recommends a 30-day self-love exercise—just 30 days where you only think about yourself. “For first daughters, one of the things you have to do is recognise you have a self first that you can return to because that is the thing that you lose as a first child, that awareness of self. Oh my god, I’m actually a person. I exist.”

Learn to Sit with Guilt

But self-awareness alone isn’t enough. The real work comes in learning to tolerate the discomfort of saying no.

“Simply because she’s able to manage the emotional complexities of her home life does not mean that she’s capable and skilled at doing the same thing for herself,” Amanda explains.

The work involves learning to say no and sitting with uncomfortable emotions, especially guilt, without doing anything about them. Then make decisions that benefit you while you’re going through that discomfort.

Deborah, who cut off her parents this year, says she’s finally sleeping through the night. Emmanuella, who moved out, describes it as “the first time I could breathe.” The healing isn’t linear, and it’s not easy. But it’s possible.

When Everything Must Burn

And then Amanda offers her most radical advice, the kind that might terrify as much as it liberates:

“There will be a time when what is required of you to truly free yourself is to let everything burn. When that time comes, even if it burns your own life, let it. What it does is that it just lays everything out in the open. Do not hesitate. If you hesitate, you only keep yourself in prison.”

“This time around, it’s not the prison of your parents’ construction. It’s the prison of your own making.”

When Amanda is asked what she wishes African parents knew about first daughters, her answer is immediate: “Just leave us alone.”

She expands on it, and the emotion in her voice is unmistakable. “There’s just so much… the weight of the expectations of your parents and others… I wish I didn’t have to go through the experience of having to shed that. I wish I were in a place where I could just be and whatever it was that I was choosing to be, my parents would just understand that it is just the experience of life.”

The desire isn’t complicated. It’s not about abandonment or rejection. It’s about space. Room to breathe. Permission to exist without the constant weight of expectation.

And then she names something crucial: “Our parents want our lives to look a certain way, but it’s not because it’s what makes us happy, it’s because it’s what makes them happy.”

The eldest daughter’s life becomes a stage for the parents’ unfulfilled dreams. And that’s not love. That’s projection.

“Just because I care about my siblings and I look after them does not mean that it has now become a responsibility. Why can’t it just be what it simply is? I’m just doing it because I’m a fucking human being, and it can be reciprocated. Why does it have to be something I have to take on, as my life purpose and duty?”

That’s what we want: To be seen as individuals. To have our care recognised as an act of love, not a burdensome duty. To be released from the expectation that our existence is only valuable insofar as it serves others. We want to be loved for who we are, not for what we can do.

And we want people to stop assuming we have it all together.

“That we have it all figured out. We don’t. That we always have money. We don’t. That we always make the right decisions. We don’t. That we know everything. We don’t. That we’re perfect. We’re not. That we don’t have feelings. We do. We can be vulnerable. We are.”

“We’re just girls, you know, who are scared.”

Click here to see what people are saying about this on Instagram.