Globally, there have been a number of youth-led protests in recent times. All around the world, young people seem to be reaching the end of their patience with corrupt, ineffective and repressive governments.

Analysts suggest Gen Z (born between 1997 and 2012) got the worst end of the stick when it comes to the economic fallout of the 2008 financial crisis. But Boomers, Millennials and Gen X probably have something to say about that.

We can argue about who has it the hardest all day long, but what is clear is that the youthful Gen Z have the energy to actually go out onto the streets and do something about their frustrations.

And that is exactly what they have been doing.

Lately there have been youth-led protests in several countries including Kenya, Morocco, Peru, and Nepal.

So, are we likely to see a Gen Z protest in Nigeria? Well, let us look at the similarities Nigeria shares with the countries that have had protests.

Kenya

In Kenya, the protests kicked off in June 2024 after the William Ruto government tried to pass a Finance Bill that came with heavy taxation including a 16 percent Value Added Tax (VAT) on bread.

After the first wave of protests, the government tweaked some parts of the bill and passed it, but the youth were still not having it. More intense protests followed.

Protesters stormed the parliament building and were met with brutal police resistance. Over 20 people died and many others were injured. But on June 26, 2025, President William Ruto announced he would not sign the bill into law.

In Nigeria, the Tinubu administration is trying to make up for a revenue shortfall caused by lower oil prices by taxing an already struggling population and turning government agencies into revenue-focused, money-printing machines.

Apart from widening the tax net through four tax reform bills set to kick off in January 2026, the government has been flirting with several other taxes on goods and services.

The Nigeria Immigration Service (NIS) has increased passport fees twice since Tinubu became president, including doubling the fees in 2025. Then there is the 4 percent Free-On-Board (FOB) charge on imported products to boost the revenue of the Nigeria Customs Service (NCS). It was suspended in February, reintroduced in August after the senate raised the NCS revenue budget from ₦6.584 trillion to ₦10 trillion, then suspended again in September due to public backlash.

The government has also floated the idea of a 5 percent surcharge on petroleum product purchases. Even the police are not left out, with attempts to bring back tinted glass permits which were scrapped in 2022 because officers were using them to extort and harass motorists.

Peru

Peruvian youth have been protesting since early September 2025. On October 22, the government declared a state of emergency to try and stop the protests, which have already seen at least 19 people injured in clashes with law enforcement.

The youth are pushing the government to do something about the country’s high crime rate. Kidnapping by organised crime groups is a serious issue in Peru.

In Nigeria, insecurity is also a major problem, and kidnapping has become a trillion-naira industry.

The National Bureau of Statistics estimated that Nigerians paid a total of N2.23 trillion as ransom between 2023 and 2024. And according to SBM Intelligence, N2.56 billion was paid between 2024 and 2025.

Nigerians have even turned to social media crowdfunding campaigns to meet ransom demands.

Morocco

Gen Z protesters in Morocco have been filling the streets since September 27, 2025 to complain about the poor state of public education and healthcare.

A big part of their frustration is watching their government spend money on hosting international sporting events like the 2030 FIFA World Cup and the 2025 Africa Cup of Nations, while public services remain underfunded and youth unemployment is through the roof.

The parallels with Nigeria are uncanny. We have all the same problems, yet Tinubu was determined to host the 2030 Commonwealth Games. Thankfully, India’s bid beat ours.

Nepal

Nepal had its own Gen Z protests in September. The trigger? The government shut down social media platforms during a viral trend that exposed the lavish lifestyles of politicians’ family members.

It has been reported that the ban was a way to pressure social media platforms into complying with a new Digital Services Tax that placed stricter VAT rules on foreign e-service providers. It was all part of the government’s plan to boost revenue.

Over 70 people were killed in the protests, government buildings were vandalised and burnt, and Prime Minister K. P. Sharma Oli, along with a few other ministers, resigned.

Nigerians are no strangers to flashy displays of wealth by government officials and their families on social media. And recently, OpenAI announced it would be increasing its subscription fee for Nigerian users of ChatGPT to account for the 7.5 percent VAT mandated by the government.

Who will barb us this style?

With how similar Nigeria’s situation is to these countries that have had protests, it is almost surprising that Nigerians have not taken to the streets already, or at least mobilised some other ways.

While a few factors have sparked protests elsewhere, Nigeria has a cocktail of all of them. Yet, Nigeria’s Gen Z remains silent.

Quite understandably, many Nigerians have been watching these protests with a bit of envy. Nobody wants chaos and violence, but it is easy to wish for a day when Nigeria’s political class finally get what many think they deserve.

But can Nigeria’s youth actually make a stand against the government like their mates have done globally?

Well, the simple answer is yes. Anything is possible. But the more honest answer? It is currently very unlikely.

The tower of Babel Nigeria

“…let us go down, and there confound their language, that they may not understand one another’s speech.”

~Genesis 11, verse 7

Nigeria has many problems, but one of the biggest is the problem of cultural identity.

Obafemi Awolowo wrote in his 1947 book, Path to Nigerian Freedom, that “Nigeria is not a nation, it is a mere geographical expression. There are no “Nigerians” in the same sense as there are “English” or “Welsh” or “French”. The word Nigeria is merely a distinctive appellation to distinguish those who live within the boundaries of Nigeria from those who do not.”

In Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s 2006 novel, Half of a Yellow Sun, the character Odenigbo says, “I am Nigerian because a white man created Nigeria and gave me that identity… But I was Igbo before the white man came.”

This sentiment still lives in Nigeria today—the idea that ethnic identity must come before the national identity of being Nigerian. This means it is still very easy to divide Nigerians along ethnic lines, and opportunistic politicians take full advantage.

In the 2023 elections, people were profiled and harassed if they were perceived to be from the wrong ethnic group. In Lagos, hoodlums stopped people from exercising their constitutional right if they were suspected to be Igbo.

Since then, there has been a rise in ethnic supremacy sentiments in the South West under the guise of “Yoruba, ronu!”

For a united stand to be taken against the government, Nigeria’s youth will have to look beyond their differences and fight for collective interests.

We came, we saw, they opened fire

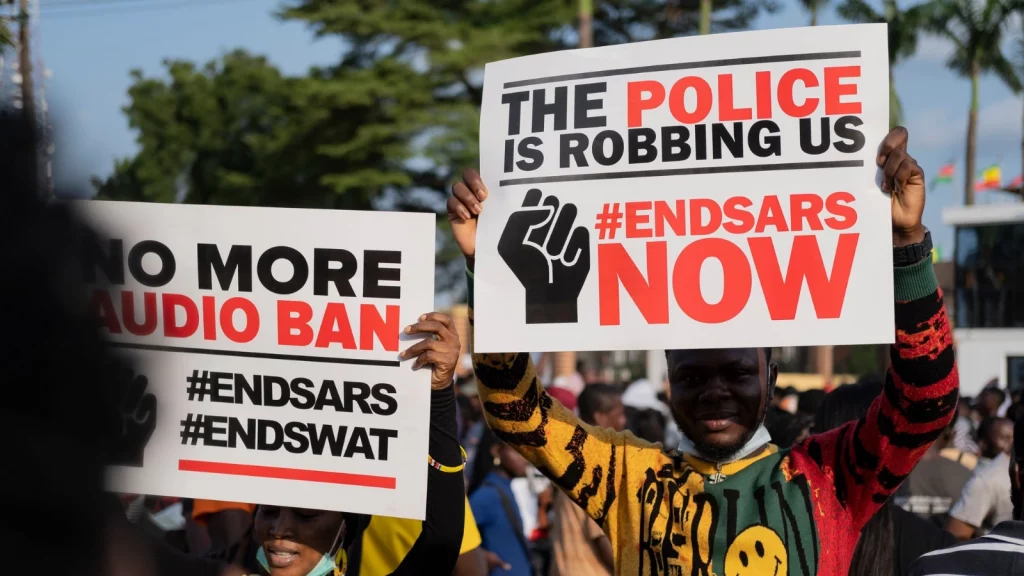

We must not forget that young Nigerians have had a nationwide movement before. And they are still reeling from the fallout.

October 20, 2025, marked the fifth anniversary of the Lekki toll gate massacre, where officers of the Nigerian Army opened fire on peaceful protesters during the nationwide EndSARS protests in 2020.

The shooting basically marked the end of the protests, which had seen young people all over the country unite under the common goal of ending police brutality and extortion.

The EndSARS protest was exactly the type of organic, united movement that has led to youth-led change around the world. Police brutality affected a wide range of young Nigerians, regardless of class, religion, or ethnicity.

But the fatal response from the government took the wind out of the sails of the youth, and five years later, they have not returned to the streets in such force again.

Whether young Nigerians can overcome the trauma of the violence they faced in order to start a similar movement seems unlikely.

Many are scared. And they have good reason to be.

What was it all for?

It is hard not to look at the EndSARS protests as a thorough defeat.

In the wake of the Lekki shooting, several All Progressives Congress (APC) members denied the events of that night. Five years later, the APC is still the ruling party.

Days after soldiers killed innocent citizens, Bola Ahmed Tinubu said those who had been shot had to “answer some questions.” He implied they deserved their fate for staying at the protest site and questioned their characters. He is currently the president of Nigeria.

Despite the Judicial Panel of Inquiry describing the events of October 20, 2020, as a massacre, none of the deniers has taken back their words or apologised. Nobody with the power to have ordered the soldiers to the toll gate has been held accountable.

Five years later, activists trying to honour the victims of the massacre by placing flowers at the toll gate were harassed by security operatives.

In August 2024, angry citizens held demonstrations and marches to protest hunger and bad governance. Afterwards, a group of minors were arrested and tried for treason which carries the death penalty. They were eventually pardoned and freed after public outrage, but the fact that the death penalty was even on the table shows the kind of culture of fear the government wants to instill in Nigeria’s youth.

In this climate, it is understandably hard to build the motivation and momentum for mass movements.

Many ways to kill rat

“A problem well stated is half solved.”

~Charles Kettering

Knowing why a youth protest would be difficult in Nigeria means we also know how to solve those problems.

Nigeria’s youth need to realise that, just like with police brutality in 2020, many of today’s problems affect all of us, regardless of ethnicity. Nigeria might be the product of colonialism, but so are many other countries where people have found ways to work together regardless. Cultural identity is not an insurmountable challenge, and a Nigeria that works for everyone is possible if we work together for it.

Many of the countries that have had successful youth protests were also met with stiff, even lethal, government resistance. But they did not back down.

If Nigerians do come out to the streets again, they must be ready for resistance from security forces. Momentum cannot be lost in the face of state violence. It must become fuel for even more stubborn demonstrations.

While it is easy to be envious of global examples of youth protests, we must not fall into the trap of seeing civil unrest as the only route to achieve the change we want. Democracy offers a peaceful way to get rid of unwanted governments.

The art of the follow-through

Three years after the EndSARS protests, Nigerians went to the polls in 2023. And while the lead-up to the election saw increased registration numbers for young people and women, the voter turnout was one of the lowest in our history.

Nigeria’s youth are its largest demographic group and, as a bloc, would be a voting majority. But they need to shake off their apathy, realise the impact that politics has on their lives, and get involved. And when elections come round, they need to follow through by actually showing up on the day and casting their vote.

We could hope for another organic protest movement that balloons into the toppling of the government in a blaze of violence and chaos. Or we can put our energy towards having a quieter but equally impactful revolution at the polls.

Dear Nigerian Gen Z, which one you dey?

Before you go, help us understand how you and other young people feel about the 2027 general elections by taking this 10-minute survey.

Click here to see what other people are saying about this article on Instagram