Wake up, it’s 2016.

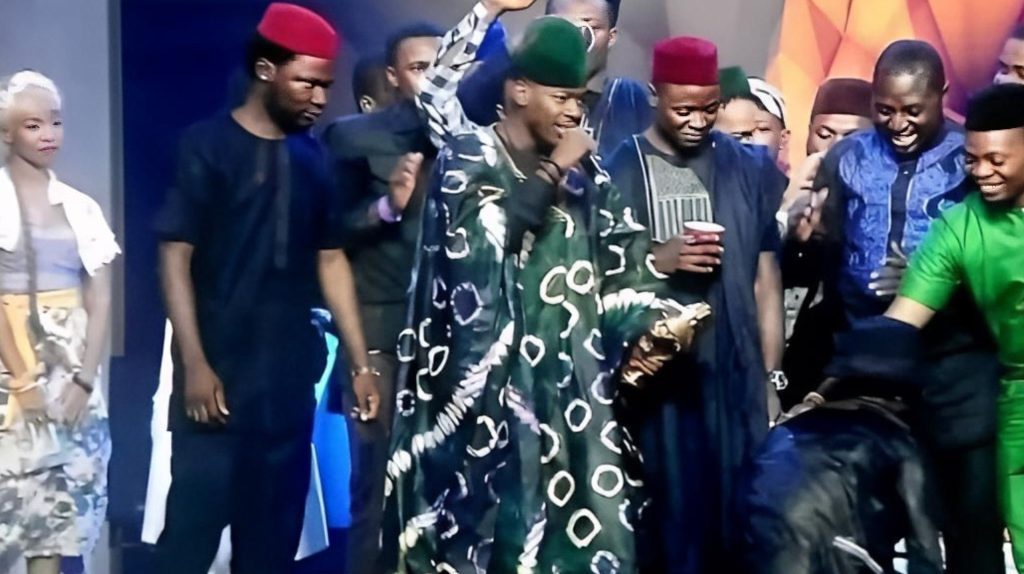

You are listening to Runtown’s “Mad Over You” or Reekado Bank’s “Problem”. Fuel is still ₦86. We are still gagging over the legendary Don Jazzy versus Olamide face-off at the Headies. And the year isn’t complete without everyone dabbing and throwing their hands in the air, dancing to Shoki.

Our outfits are not complete without chokers. We are taking pictures with selfie sticks. Skinny jeans are the talk of the town. How can you be a happening babe if your jeans aren’t tight enough to cut off the blood flow in your legs?

For many young people, 2016 signifies the good old days. 10 years ago is more than enough time for your life to go from better to worse. That would explain the glee with which many people are hopping on the 2016 throwback trend, posting their Snapchat filter selfies with the dog ears and flower crowns.

But 2016 is not our first rodeo. The comeback of the Y2K aesthetic and our obsession with old Nollywood memes all point to one thing: Gen Z is obsessed with nostalgia. But what is driving this?

The Internet’s new obsession

People’s obsession with nostalgia is not necessarily new. If you sit down with any Nigerian aunty for five minutes, she will tell you about the ‘Good Old Days’ of the 70s and 80s. She’ll mention when the Naira was equal to the Dollar and school fees was just ₦20.

Clay Routledge, a psychologist who studies nostalgia, explains why we cling to it so much. According to him, it helps give life meaning and allows our brains to filter out the bad stuff and curate a highlight reel of the good times.

Fun fact, nostalgia used to be considered a mental illness—which, honestly I kind of get. But then, with more research, it transformed into what psychologists now call a poignant experience.

Is all that glitters really gold?

While we were dabbing and dancing to shoki in 2016, Nigeria was also collapsing. The country slipped into recession for the first time in 25 years.

The Super Falcons won the African Women’s Championship in December and had to stage a protest because the government refused to pay their allowances. They literally refused to hand over the trophy.

Oh, and let’s not forget MMM, the forerunner of modern Ponzi schemes in Nigeria. After promising 30% monthly returns to investors, it collapsed spectacularly.

In the North, Boko Haram was carrying out its most vicious attacks. And to crown it all off, it was the year our dear President Buhari went to Germany and told the world that his wife belongs in “the kitchen and the other room.”

We all love a good pair of rose coloured glasses

I must admit, there’s nothing profound or new about what I’ve just said. We are not stupid. We remember some of our parents’ businesses struggling at the time. We also most definitely remember the MMM collapse.

Yet we are still romanticising 2016 as if it were the best thing since sliced bread.

We are doing this because 2026 is worse. And in ten years, we will look back at 2026 with the same selective memory.

We already see it on TikTok, with the romanticisation of 2020, even though we were on lockdown during a literal pandemic. It is still happening with the early 2000s; we obsess over the Y2K aesthetic but forget that a SIM card cost ₦30,000 back then.

The reality is that our economy has gotten significantly worse. Fuel has gone from ₦80 to ₦1,000 over the past 10 years. 50k no dey last again.

Our experience with social media hasn’t been spared, either. Back in 2016, Evan Spiegel wasn’t making us pay for Snapchat. Our Instagram feeds were still chronological, and Mark Zuckerberg wasn’t obsessed with algorithms.

It is all too easy to put on rose-coloured glasses when looking back at the past. One writer notes that 2016 nostalgia might be the best way to deal with the new year funk. I’m going to take it a step further and say it is our way of dealing with the horror that is our current lives.

And at the end of the day, that’s fine.