Like many infrastructure projects, road construction is often seen as a pathway to economic growth and improved quality of life. But for Kilankwa 1, a community on the outskirts of Nigeria’s Federal Capital Territory (FCT), Abuja, this promise has turned into tragedy.

In 2021, Wadata Group began construction of a 3-kilometre road, sparking joy and hope among residents. That joy was short-lived. The company did a shoddy job, leaving behind not just an inconvenience but also a trail of suffering. In this investigation, Chigozie Victor journeyed to Kilankwa 1 to uncover the truth behind the abandoned project, funded with public money, and to reveal the human costs of poorly executed projects.

Hajara Muhammed felt her world spin and shatter the day her 17-year-old son, Nasiru Yusuf, died; it felt like a fever dream, yet it had happened.

It was just like any other day. Nasiru had returned from school from neighbouring Kilankwa 2. He had joined her on the farm and left afterwards for his job outside as a security guard. He was supposed to return home to her again, except he didn’t.

While he rode his motorcycle to work, he tried to dodge an approaching car from the opposite side of a junction, but he couldn’t. The pull of the road was stronger than he could resist, so he unsuccessfully tried to dodge the car, but it hit him, and he fell headfirst to the ground.

A dazed Hajara rushed to the scene of the accident, where she and her older son, Abdurrahman, took Nasiru to a hospital in nearby Gwagwaada.

Nasiru died before he could receive any treatment.

As Nasiru’s body went cold, so did Hajara’s. The only difference is she’s still alive… Barely.

“…He was still in school. Just in SS1 (Senior Secondary School), He used to sing. He wanted to be a musician,” Hajara said, wringing her hands.

“I truly miss him. He was a musician and earned a little money from it, which we used to buy food. We ate and drank from what he provided. Sometimes he would go to occasions, and once he started singing there, they would give him food, and he would bring some back for us,” she said, explaining that her little family fed well because of him, even though he was only a teenager.

The many costs of road abandonment in Nigeria

like Hajara, many people across Nigeria have lost loved ones to the menace that is road abandonment.

In 2023, for instance, RCDIJ investigations shared the equally devastating story of Ugwu Obinna, whose little sister was crushed to death due to a road crash resulting from potholes in the abandoned old Enugu-Onitsha road.

Similarly, a 2023 Investigation by CrossRiver revealed how families lost loved ones, incurred financial losses and many more as a result of an abandoned road project in the Yala-Ogoja area of the state.

These are not one-off experiences. A 2017 study published in the Journal of Economics and Sustainable Development sheds more light on the prevalence of road abandonment as well as its human costs. Findings from collated data revealed that loss of lives (at 88.5%) accounted for the leading costs of road abandonment. Others include loss of properties (at 91.5%) and erosion at 93.5%

According to the WHO, 1.3 million people die globally every year in road crashes, with Nigeria accounting for an estimated 41,693 deaths—about 2.82% of the global toll—placing the country 54th worldwide in road accident rankings. The WHO highlights structural factors such as road abandonment as causative factors.

Despite the human and economic factors associated with road abandonment, the practice has remained prevalent over the years. As recently as 2024, the Chartered Institute of Project Managers of Nigeria (CIPMN) estimated that over ₦17 trillion-worth of projects—including many road projects—have been abandoned nationwide

Studies have linked this terrible practice in Nigeria to factors such as lack of continuity in government, poor planning, financing, budget delays, policy inconsistencies, corruption, and capital mismanagement.

This reporter visited the Kilankwa 1 community in the Kwali Area Council of Abuja to investigate a road abandonment project and its human costs. Like Hajara, many more in this community have suffered great losses caused by the road; from a father who is still haunted by the image of his son’s intestines bursting out of his lifeless body, to others who had near-death experiences.

Several community members alleged that Wadata Group Limited abandoned the 3KM road project halfway. However, when the reporter reached out to Wadata Group Limited, it told its own story, insisting that the project was done to government specifications .

The loss of a lifetime

Nasiru’s older brother, Abdurrahman, misses him dearly too, and he is deeply concerned about his mother’s well-being following his death.

“My mother always asks about him. Even the day before yesterday, when we went to the farm together, she kept on crying, saying we would have finished at the farm faster and gone home. She said his absence on the farm was disturbing her, so I consoled her, telling her to leave everything in God’s hands,” he recalled.

“He was buried there,” Abdurrahman said, pointing towards a bush path.

As he walked to Nasiru’s grave, Abdurrahman recounted how his late brother would not eat unless he were sure Abdurrahman had something to eat too; how joyful he was and how he spread it throu⥜gh his music, and how loving and kind he was.

“He had no problem at all; he was such a happy boy. He was so happy,” Abdurahman continued, explaining how they would gist among themselves, bantering over school and politics, and how all of that has drastically changed because their home is now devoid of joy.

Beyond his own grief, Abdulrahman feels helpless about his mother’s. A huge part of her had died with Nasiru, and he did not know how to bring her back to life. He had watched helplessly as grief weakened her, snuffing life out of her small food business. Though she farms now and takes up side hustles, she still struggles financially, and he is eaten up by the discomfort of being unable to provide for her in the way that he wants to.

“Sometimes, she will say ‘I don’t see him, I don’t see him,’ but I will say, ‘he’s dead, you can no longer see him,” Abdurrahman said.

Hundreds of Millions of Naira Down the Drain?

Kilankwa Road used to be an endless stretch of unpaved earth. Four years ago, when residents of the community learnt it was to be constructed, they were full of excitement. Their long-held prayer for a tarred road to drive the economy of the community was finally being heard. But the joy would not last.

Many residents of the farming community continue to tell tales of hardship, especially during rainy periods when the road turns into a death trap, becoming a nightmare and casting a bleak shadow on the area.

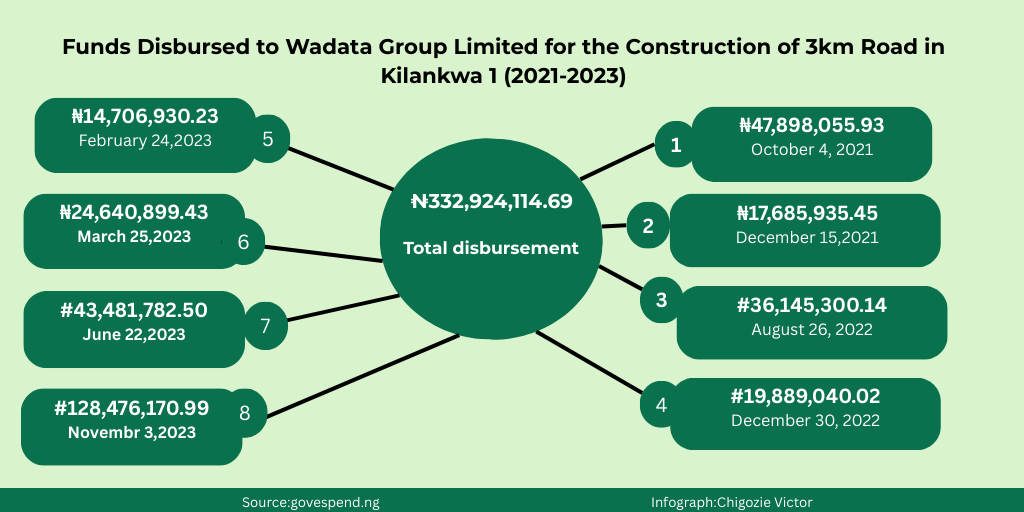

Data from BudgIT’s govspend showed that a sum of ₦332,924,114.69 (Three hundred and thirty-two million, nine hundred and twenty-four thousand, one hundred and fourteen naira, sixty-nine kobo) was disbursed to Wadata Group Limited for the construction of the road.

On one of the days this reporter visited Kilankwa, it would be hard to convince a ‘newcomer’ that the road had gulped hundreds of millions of Naira in public funds to construct just a few years back

As the motorcycle I boarded drove past the community signboard, a stretch of untarred road lay steeply ahead. Its surface had large patches of cracks, and the gravel had worn away from years of neglect.

The motorcycle shook from the effect of the gravel, as small pieces of the stones occasionally skidded off, even as the motorcyclist tried to dodge the potholes.

The contractor only constructed the connecting bridge and graded the road before a truckload of gravel was poured onto its surface. Residents of Kilankwa 1 insist it was abandoned halfway.

“They (contractor) took their things and left,” Haruna Musa, a resident of the community, said.

“We expected to see them come back to complete and transform it to a normal tarred road, but they never did,” Haruna said, explaining that the gravel caused the road to pull people in a way that made them lose control of their vehicles.

The road that keeps taking

Nasiru Yusuf was not the only one who had died as a result of fatal injuries sustained on the road. Abu Salihu was only 15 years old when his life was cut short in a ghastly accident caused by the state of the road. Though both boys were not peers in age, they lie side by side now in two graves a few walks away from the centre of the community.

Abu’s father, Musa Salihu narrated it briefly: One morning, after Abu had finished preparing for school, he walked about outside and was hit by a car which had come to pick up farm produce from the community.

When asked to consider that Abu’s death may have been caused by recklessness on the part of the driver, Musa refused it, insisting that the badly constructed road caused.

He explained that the driver of the car struggled to resist the pull of the gravel on the road, leading to the crash, which killed his son.

“The road drags people, and carries their hands against their will,” Musa said.

“I haven’t forgiven them (contractors),” he continued, recalling all over again how some people had come to his farm that morning to fetch him and how he saw his son’s body at the scene of the accident, his intestines splattered on the ground.

“I still grieve. I haven’t gotten over it. Even today, I still cried,” Salihu said.

More victims

Jibrin Shuaibu knew the roads all too well. He had seen the gravel pull people to the ground, leaving them bloodied and scarred. Each time, he counted himself lucky and prayed he would never get caught in its grip.

For a while, he didn’t. But one Saturday morning in 2024, Jibrin headed out to the market on a commercial motorcycle. As the motorcyclist navigated the unpredictable road, he spotted a car approaching from the opposite direction. Its tyres skidded as the driver fought to steady it against the gravel’s pull.

Not wanting to stake their lives on the probability of the other driver’s success, the motorcyclist swerved sharply to the left, but the loose stones pulled him down; the motorcycle slid out of his control. Jibrin and the motorcyclist fell violently to the ground, leaving them badly injured.

Jibrin does not remember much of what had happened in the instant following the crash, but he remembers feeling like the bone in his leg had shattered. He was taken to the Specialist Hospital in nearby Gwagwalada. When it was clear he was not getting any better, he was taken to Birnin Kebbi, Kebbi State, where his leg healed.

In the weeks that followed, Jibrin not only suffered a hit to his health and finances, he also had to watch helplessly as his family suffered.

“That time, there was food scarcity in my home because all the money I had was being put towards my recovery. I had some land I purchased before, but I sold it and gathered the money for treatment. My children were starving; there was nothing to eat. Some people were helping me financially, chipping in where they could because of the situation I found myself in,” he remembered.

Though Jibrin’s incident happened a year ago, he continues to suffer both physically and financially. While he is able to relieve the physical pain by taking medication from time to time, he cannot do much about his finances.

Once combining interstate driving with farming, he now drives sparingly within Abuja, “I used to go to Kogi, Nasarawa, Minna, and Jos, or anywhere my movement carries me. But since this incident happened, I can’t go interstate any longer. I just go to Zuba, Suleja, and Abaji.”

“I farm (to make up for finances). It doesn’t really affect me there because I can be threading softly. Also, when I have some money, I pay some people to go and do the heavy lifting for me,” Jibrin said, his eyes fixed to the ground.

“We didn’t abandon the road”

After two visits to the Wadata Group’s office and several check-ins, , the chairman, Alhaji Umaru Wakili, told this reporter that, contrary to the community’s claims, his company did not abandon the construction of the 3KM road.

“We were contracted to do surface dressing, and we have completed the scope of the job. There’s surface dressing and there’s asphalt. That road is surface dressing, not asphalt done with concrete.

“Anywhere there’s surface dressing, you see stones on the road,” Wakili explained, emphasising that surface dressing is usually done to make bare roads usable, not necessarily smooth.

Wakili went further to explain that his company was asked to construct a bridge to waylay the water which caused recurring flooding in the community and made the road hard to use especially during the rainy season.

“Jobs are given in phases. After this surface, we were supposed to be awarded the one for asphalt, but unfortunately, it didn’t come that way.”

“That road was a constituency project. I don’t know why, but sometimes, the government takes time to award the completion of roads like this,” he said, emphasising again that his company rehabilitated the road as they were contracted to do, and did not abandon it.

But is Wakili right?…

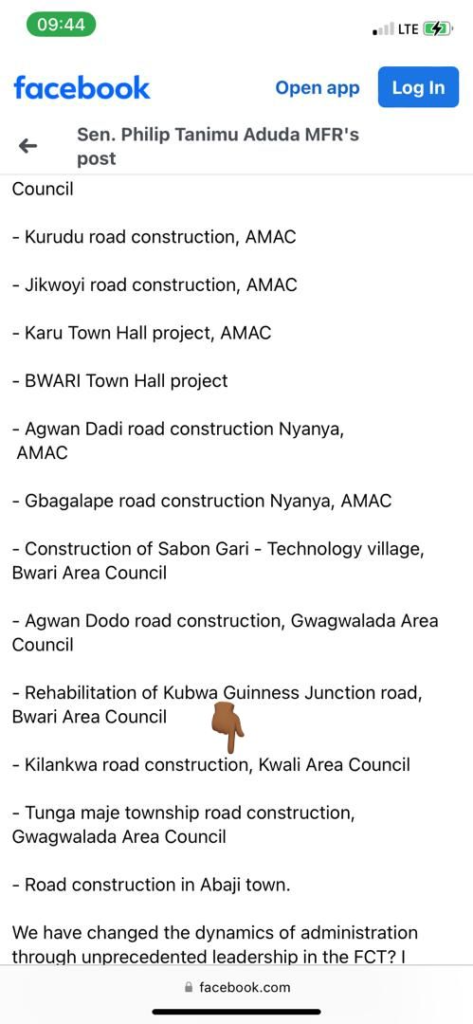

The road was constructed in 2021. At the time, Senator Philip Tanimu Aduda represented the Federal Capital Territory (FCT) and, in extension, Kilankwa 1.

Though he is no longer in office, the project was still traced to his office via a Facebook post he made recounting his achievements as FCT Senator.

To understand how such projects are funded, this reporter spoke with a representative from BudgIT’s Tracka platform.

Tracka’s Communications Officer, Ademide Ademola, said:

“Constituency projects are initiated by legislators of respective constituencies across Nigeria. Legislators gather projects across their constituencies either by holding Town Hall meetings or taking the recommendations from written requests of their constituents.”

When asked how constituency projects are funded, Ademola explained that legislators nominate select projects for their constituencies in preparation for a budget year.

“After the projects are proposed by the legislators, deliberations are held, and after the deliberation phase, select projects are included in the national budget of said year, and passed.”

“The project is then funded through the Office of the Accountant General of the Federation. Before they are given out by contracting agencies, the open bidding process is initiated and often announced in national newspapers as mandated by Nigeria’s procurement procedures.”

The Bureau of Public Procurement (BPP), Nigeria’s regulatory authority established by the Procurement Act 2007, is responsible for the monitoring and oversight of public procurement, development of the legal framework and professional capacity for public procurement (among similar duties). It is also the agency which compiles the Procurement Procedures Manual, a policy book containing rules and regulations guiding procurement in the country.

The latest edition of the manual states that procuring entities must publish open up contract bidding to the general public by advertising bidding invitations “on the notice board of the procuring entity, any official websites of the procuring entity; at least two national newspapers, and in the procurement journal not more than four weeks for contracts within the thresholds of the Parastatals and Ministerial Tender’s Boards and not more than six weeks for contracts above the threshold of the Ministerial Tenders Board before the deadline for submission of the bids for the goods, works and services.”

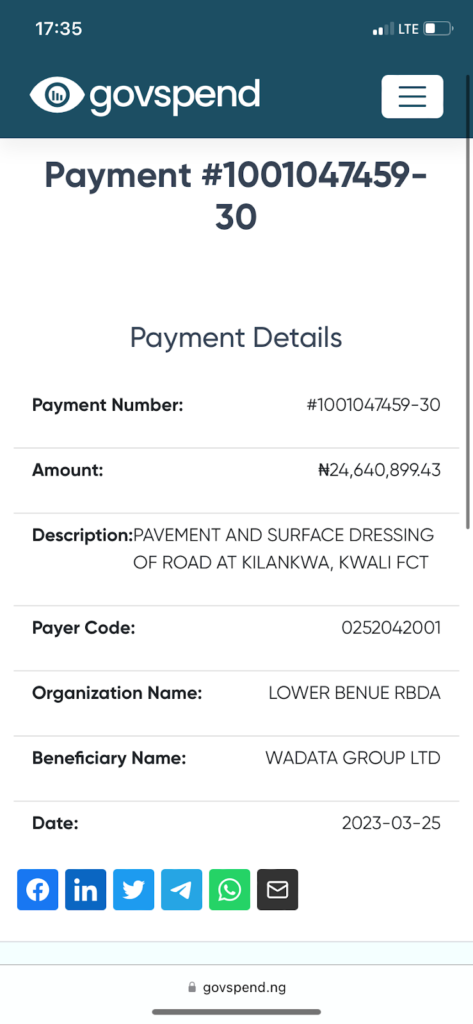

The procuring entity in this case is the Lower Benue River Basin Development Authority (RBDA), a federal parastatal under the Federal Ministry of Water Resources

The bidding was published on publicprocurement.ng, however, there was no trace of the advertisement in any national daily or the procurement journal of May 2021.

Meanwhile, a look at the scope of work of the project published on the platform listed the project as Construction of 3KM Road and Drainages. It did not specifically mention Surface Dressing, as stated by Wadata Group.

To further investigate Umar Wakili’s claims on the scope of work awarded to his company, the reporter revisited the payment details provided by BudgIT’s govspend platform. This time, it’s noted that five of the eight payments the company received from Lower Benue RBDA had Surface Dressing in their descriptions. The rest were titled Construction of 3KM Road and Drainages Kilankwa, Kwali FCT Senatorial District.

According to this, Wakili’s claims about the scope given to him do not exactly check out.

Wakili’s company was also contracted to construct drainages in addition to the road. However, this was not seen in the community. Instead, a culvert was constructed.

Michael Olufemi, an expert in civil engineering, said that the contractors did not fulfil that part of the project, as culverts and drainages are two distinct things.

“Culverts are different from drainages. A culvert is the box-like one that water passes under, while drainage is the one that water flows into.”

“Drainage is better known as a gutter in local language,” said Olufemi, poking holes into the amount spent on the road. Olufemi mentioned that the amount of money seen on govspend.ng (₦332,924,114.69) could not have been earmarked for surface dressing alone, as it was sufficient to cover both phases of road construction— surface dressing and asphalt.

“As of 2021, that money should have done more than surface dressing. I will put asphalt on that road with that amount (at the time).”

“Things were cheaper at the time, unlike now. Now, things are almost five times the price they used to be,” Olufemi said, expressing surprise that a constituency project was concluded at the surface dressing level.

Experts weigh in

Though the Chairman of Wadata Group Limited dismissed the accidents and deaths recorded in the community since the construction of the road, our findings offered a glimpse into the danger residents of the community have been contending with

Studies have shown that several authorities declare surface dressing as a safe form of road construction. Durham County Council, for instance, describes it as the major type of surfacing “ideal for all roads.”

Surfacedressing.com lists provisions for skid-resistant surface and waterproofing of road (to prevent water ingress, reduce cracks and prevent potholes), as some of its benefits.

No source seemed to flag surface dressing as remotely dangerous; they did, however, state that it is unsafe to fast traffic immediately after it is laid, recommending that temporary signs be put in place, asking road users to drive at low speed. When asked if the constructors installed such signs or educated them about speed limits, the community members could not confirm this.

While speaking on the possible cause of the numerous road accidents in Kilankwa 1, Engineer Michael Olufemi affirmed that speeding immediately after the road is constructed could indeed lead to accidents.

“When this gravel is still new, and you are speeding, you can lose control. In fact, even a trailer can miss control because when you want to match brakes, the gravel will speed you up because there is no frictional contact to the ground; it is the gravel that is helping you to move,” he said, explaining that speeding when the road gravel is yet to settle into the Bitumen could be the cause of the accidents.

“They (the contractors) could have introduced bumps in the community to reduce their speed limit, seeing as it’s a community that is not familiar with this,” he said.

But when Olufemi was told that the accidents still happened as recently as July 2025, and shown photos and videos of the road, his stance immediately changed.

“They (the Kilankwa community) are right,” he said, referring to their description of the road as having a pull, forcing their hands and making things as little as braking and turning difficult to the point of road clashes.

Idachaba Adejo, a Civil Engineer with many years of experience, agreed with Olufemi. He mentioned that “surface dressing has never been a source of accident to anybody. I’m even surprised to hear a community saying they are having accidents because of surface dressing,” he said, going into a detailed explanation of the processes involved in surface dressing.

“It is an aspect of road dressing done to give way for a larger one in the future..”

“…The chippings (gravel) to be used are fine chippings: If they used bolder materials, then it’s a serious concern because they are supposed to use fine chippings,” he said.

Upon hearing that some of the gravel skids off the road, Adejo speculated that the size used was not the recommended size.

His conviction became stronger when he saw photos of the gravel and heard the community’s description of the road as having a pull.

“I can confidently tell you that the chipping they used for that construction is not the normal chippings you use for surface dressing. Surface dressing chippings are so fine (little) that they will be buried inside the bitumen, which was sprayed and bonded, so that they form a layer on their own and are buried,” he said.

Trapped in silence

Besides the wrong size of chippings used in constructing the road, a good part of the road is now riddled with potholes, a situation which Engineer Emmanuel Olufemi attributed to the lack of a proper drainage system.

Speaking on the road’s condition, Olufemi emphasised that a new one must be constructed for the community as a matter of urgency.

“This road is already gone,” he said.

But is a new road possible in the nearest future? It does not appear so, at least, not according to the explanation given by Tracka’s Communication Officer, Ademide Ademola.

Explaining how constituency projects are nominated, Ademola stated that sometimes, it is challenging for legislators to successfully clinch funds for all phases of a road project that they consider important.

“Sometimes, they have to wait for another budget cycle to come because that’s when the project can be accommodated in the budget.”

Asked if this means the community would not get the help they need anytime soon, Ademola clarified that they can.

“Of course, they can get help. The 2025 budget has been passed, and I don’t know if the project was included or not. If it wasn’t, they can keep writing their local representatives to bring attention to the road,” she said.

But can the Kilankwa 1 community afford to wait it out?

***This report was facilitated by the Wole Soyinka Centre for Investigative Journalism (WSCIJ) under its Report Women! Female Reporters Leadership Programme (FRLP) Fellowship, with support from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

[ad]