When Anita* (32) moved to Lagos ten years ago, she believed staying with her aunt would be a safe, temporary step toward independence. Instead, what began as a warm, supportive relationship slowly turned suffocating, and she had to risk everything to escape.

This is Anita’s story, as told to Mofiyinfoluwa

The first thing that hit me about Lagos was yellow. Yellow buses swarmed the roads in the park, horns blaring until I felt almost assaulted by the noise. It was November 9, 2014, and the harmattan dust clung to my skin as I dragged my boxes through the chaos, searching for the kiosk where my aunt said she had parked.

When I finally spotted Aunty Uche, I almost didn’t recognise her. The last time we met was at a family gathering in Enugu when I was still a child. In person, she looked smaller than the glamorous woman from her Facebook pictures.

Even with a smile, the tired lines on her face betrayed her age, but her hands gripped the steering wheel with the confidence of someone who owned the road. She was warm as I slid in beside her, asking about home, my parents, and my year in Sokoto. For a moment, I let myself relax. Maybe this wouldn’t be so bad after all.

***

I had spent my service year in Sokoto, and while it was a fun experience, I knew I couldn’t stay. The run-down primary health centre where I served drained me, and the thought of settling back in Enugu with my parents didn’t appeal either. Like most graduates with big dreams, I had my eyes set on Lagos. If I wanted to grow, a private hospital there felt like my best chance.

By the end of service, I scraped together just enough from my ₦19k allowance rent a small place. So when my parents asked about my next step, I told them Lagos.

But my mum had other plans. “My eldest sister is in Lagos,” she said. “She’s very comfortable. Why not stay with her?”

My first instinct was to refuse. I had never lived long-term with a relative, and the idea unsettled me. But my mother would not let it go. She painted glowing pictures of her sister’s life, a spacious duplex with just her and just one of her children. My dad also chimed in, reminding me how much I could learn from a retired nurse.

In the end, I gave in. Saving the money I set aside for rent sounded appealing. So, I packed almost everything from my childhood room in Enugu into two boxes and boarded a bus to Lagos.

That first month with Aunty Uche almost felt sweet. She drove me around the city in her air-conditioned car as I dropped CVs at hospitals. Whenever disappointment clouded my face, she patted my back and told me not to worry.

At home, I tried to repay her kindness. I washed her clothes, helped the maid, and worked long hours at the pharmacy her daughter Onyi* ran. At the end of the month, when she pressed ₦10k into my hand, my heart swelled with gratitude.

By January, I finally landed a job at a private hospital with a ₦50k monthly salary. At first, I thought I could keep everyone happy. After my shifts, I still forced myself to show up at Onyi’s pharmacy. But the new job was nothing like I had experienced. The hours were brutal, the protocols endless, and on most days, I ranon fumes. It became impossible to do both. So I decided I’d only go to the pharmacy on weekends.

They didn’t fight my decision but overnight, their warmth disappeared

***

I first realised the change one evening at the cybercafé where I spent most evenings filling out Masters applications. My phone rang. It was my uncle. His voice tore through the speaker, sharp and accusing.

“If it’s man you came to Lagos to follow, tell me now!”

I froze, struggling to process his words. “Uncle, what are you talking about?” I asked.

But he kept shouting. My aunt had told him I was “going all over Lagos, following men” since I started working. That my new job had changed me.

I stared at the computer screen, the cursor blinking on my half-filled application form, and felt my stomach drop. What exactly had I done wrong?

Before this job, I was their perfect errand girl. I ran the pharmacy, scrubbed and cleaned, even bought fruits on my way home. The moment I tried to build a life of my own, all that goodwill expired.

The rules of the house began to change. They’d stopped paying me even though I still spent my weekends at Onyi’s pharmacy. But that wasn’t the worst of it. One afternoon, I came home from work and found Aunty Uche seated on my bed, legs were crossed and bouncing slowly as if she had been rehearsing what to say.

“I can no longer accommodate you for free,” she announced. “The house runs on bills, and as you know, I’m retired.” She paused, then added as she rose to leave, “₦10k every month shouldn’t be too much for you to pay.”

I stood dazed, staring at the impression her body left on my bedsheet. What did she need my money for when her other children abroad sent her money every month?

Still, at the end of each month, I withdrew the cash and placed it in her hands. She took it each time without a flicker of hesitation. Even when she went on vacation to the US for two months, she instructed me to keep the payments aside until she returned.

My cousin also made life unbearable. She sneered with disdain whenever I greeted her. One morning, after a long night shift, she asked me to help fill in for someone at her pharmacy. When I told her I couldn’t go because I needed to rest, her eyes widened with shock.

“If I ever find you lying on that bed in the daytime, I’ll pour you hot water!” she screamed.

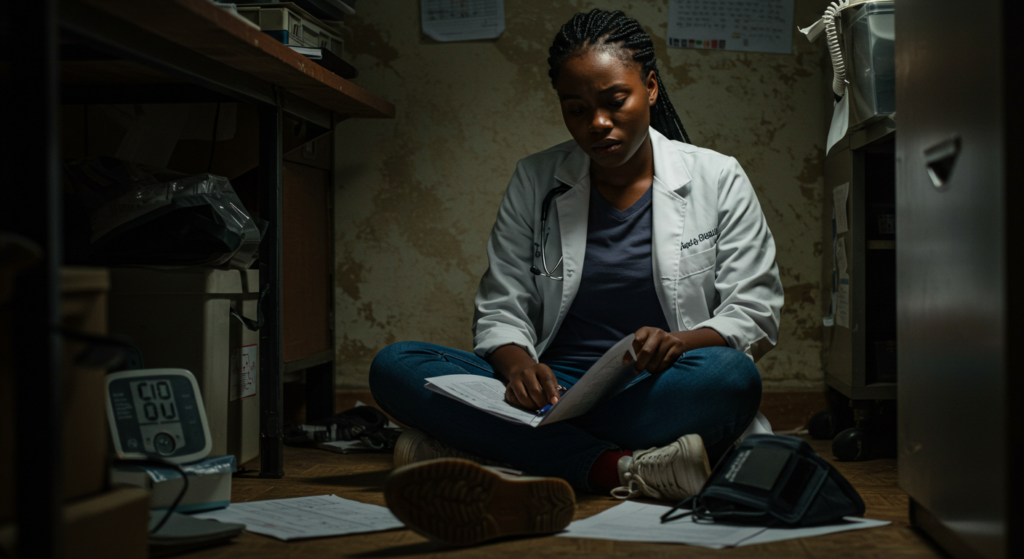

From that day, I avoided sleeping during the day. After night shifts, I curled up on the cold tiles of the floor. My bones ached every morning. The help would sometimes glance at me with pity as she swept around my curled-up body.

***

One night in August, after crawling through heavy traffic from Ikeja to Berger, I finally reached the gate close to midnight. My legs ached, and sweat glued my shirt to my back. I slid my key into the lock, only to realise the gate had been bolted from inside.

Panic set in. I dialled both my aunty and Onyi over and over, but neither picked up. When the maid finally answered, her voice was a whisper. “Madam said I shouldn’t pick your calls or open for you.”

I stood outside the compound for an extra hour, muddy from trekking part of the way, tears burning my eyes. After several desperate calls, she finally let the maid open up. Inside, I greeted Aunty Uche, trying to explain that the traffic had been so bad it made the evening news. She just hissed loudly and turned her face away.

Not long after, she demanded I hand over the house key. From that moment, every time I returned, I had to knock and wait like a visitor.

Each time, I’d call my parents in tears to vent. My dad was always furious, his voice rising over the line, but anger alone couldn’t change anything. I no longer had enough money to move out, and they simply couldn’t afford to set me up on my own.

My mum tried a softer approach, pleading with her sister to take it easy on me, but that only backfired. Aunty Uche would dismiss everything as lies, then call their brother to complain about how my mother was meddling in her home. Each time, things only grew worse. I stopped complaining altogether.

***

The breaking point came around Onyi’s birthday in October. They had planned a lavish party at an event centre not far from my hospital. I looked forward to it and even splurged on an expensive dress from a boutique. But at the last minute, a new shift landed on my schedule. When I explained, they hummed sarcastically.

That night, as music from the party floated faintly into the hospital compound, I sat in the nurses’ lounge eating bread and sardines. Out of curiosity, I texted the maid to ask how it was going.

She bluntly replied that they couldn’t stop complaining about me on the way there. One by one, she listed their complaints: that I was “cold” around them, lazed about the house, secretly watched their TV when they were out, and lied about being at work.

The next evening, after a long stretch of extra shifts, I dragged my bag into the house, exhausted. Even with what I’d heard, I didn’t expect what came next.

Onyi snatched the bag from my hand and flung it to the floor. Before I could protest, she tore through my belongings, demanding, “Where are the condoms in your bag?”

Aunty Uche sat to the side, watching quietly. I didn’t even have the strength to defend myself. They had invented a mystery man in their heads, and I was tired of sounding like a broken record denying he existed. Of course, Onyi found nothing. I simply gathered my things and went to bed.

The house no longer felt like a home. It was a cage. Every day I woke up with a knot in my chest, dreading what new accusation or insult would come.

It was the maid who finally said it out loud. One afternoon in mid-November, as we folded laundry in the backyard, she leaned close and whispered, “I can’t continue here. Too much work, too much wahala, and the money isn’t worth it.” She told me she would leave in December.

Her words struck me like a bell in my chest. If she, who was at least getting paid, could walk away, what did that mean for me working for free? Right then, I made up my mind. I had to leave too.

***

At work, I began plotting my escape. Renting a place of my own wasn’t an option. Between sending money home to my parents and siblings, and giving Aunty Uche ₦10k every month for “house expenses,” I had almost nothing left.

The hospital had accommodation reserved for house officers, but I wasn’t entitled to it. My only lifeline came from one of the doctors, who quietly agreed to let me squat in her room after I broke down and told her my story. The plan was risky. If we were caught, it could mean a query from management, maybe even losing my job.

But I was that desperate. Even fear of being discovered felt lighter than the weight of staying in that house.

So I spun a lie. One evening in early December, I sat across from my aunt and cousin with forged admission documents spread neatly in my hands.

“I got into the University of Ibadan for a Master’s program,” I announced. “Classes start in January, so I’ll need to leave this weekend.”

Their faces lit up. They clapped, showered me with congratulations, completely satisfied with the excuse. They didn’t know I had already started moving my things out.

On my final day in that house, I hugged them goodbye, took my bags and walked out through the gate without looking back.

At the hospital quarters, I pushed open the door to the tiny, stuffy room I’d be sharing and felt relief wash over me. That night, before sleep claimed me, I deleted their numbers and blocked them.

For the first time in months, I slept like a baby.

***

I thought cutting ties with Aunty Uche and my cousin would bring closure, but their memories have stayed with me. Years later, after I relocated to Canada in 2022, my mother told me how elders scolded Aunty Uche for how she treated me during a family meeting. They all agreed she went too far. She accepted and eventually apologised.

But not to me.

I swallowed the humiliation until it turned sour in my stomach, yet I never heard her say, ‘I’m sorry.’ The pain I felt was raw, as if it had just happened.

When my mother died last year, people whispered that Aunty Uche asked after my wellbeing at the burial. My father begged me to let it go and reach out to her. But all I felt was steel in my chest. To me, she was as good as a stranger.

I don’t know her,” I told him. “And I never want to.”

*Names have been changed for anonymity

Read Next: Na Me F— Up?: I Checked My Girlfriend’s Phone and Found Flirty Messages With Rich Men