Every week, Zikoko seeks to understand how people move the Naira in and out of their lives. Some stories will be struggle-ish, others will be bougie. All the time, it’ll be revealing.

What’s your earliest memory of money?

I can’t recall an exact age, but I’m the first of four children, so I kind of understood the importance of money early on. Whenever our parents weren’t around, I’d want to play the big brother role, buying my siblings candy and biscuits to keep everyone happy.

I needed money for that, and one way I made money was by playing rubber band games — where you’d throw a rubber band to try to overlap or go further than the other person’s rubber band.

Ah. I remember those games

My friends and I would contribute ₦20 to play the game. If there were five of us, that was ₦100 in the pot. The winner took half of that, while the rest shared the remaining ₦50. That’s how I made small money here and there for snacks.

To be fair, my parents used to buy us snacks and give us pocket money, too. But like parents typically do, they didn’t allow us to take things they felt were detrimental to our health, like ice lollies and other sugary stuff. So, the extra money I made allowed me to buy things they disapproved of out of my own pocket.

What was the financial situation at home growing up?

We weren’t hungry, but I noticed differences in how others lived. For instance, my dad worked in a bank for 25 years, but it didn’t do much for our finances. A family friend worked in the same bank, and they had their own house and official car, while we lived in a rented apartment.

Around the time I was leaving secondary school, the CBN’s bank consolidation policy under Soludo cost my dad his job. My mum, who was a teacher, had to take up the financial burden. I also had to learn to fend for myself, especially when I got into uni in 2003.

How did you do that?

I studied Architecture, and there’s something we call “tracing.” After completing a design, we had to present them on tracing paper with ink for assessments. The paper was fragile and expensive, and many people struggled to trace their designs without making errors or tearing the paper.

I mastered tracing quickly and started charging ₦1k per sheet to help other students — both senior and junior colleagues. Each design usually required a minimum of 10-12 sheets, so sometimes I was making up to ₦20k and more from my clients.

So it was a lucrative gig?

It was. A lot of people came to me. Sometimes, I even contracted gigs out to other people when I had too much work on my hands.

I wasn’t receiving pocket money from home — most of what my siblings and I got was food — so the money came in handy for school needs and handouts. I also regularly sent money to my siblings, who were also in university, so they wouldn’t have to disturb our parents either.

I relied on that stream of income throughout my time in school, both in my undergraduate days and my master’s degree, which I started immediately after I completed my undergraduate in 2009. I didn’t see the point of returning home to wait for NYSC when I could just finish my studies. Also, I liked the course and knew I could make money (through the designs) from being in school, so I just stayed back.

How did you fund a postgraduate degree?

Tuition was more expensive, but it was possible to resume without paying tuition at my school. You just had to make sure you had paid by the time exams rolled around.

So, during the semester, I gathered the money by taking on more tracing work, dabbling in multi-level marketing and doing random gigs with friends for money. We even had a stint running a game house, where we charged people to play games. I also got a contract to design invitation cards for an FYB event one time.

To put it simply, I was in survival mode.

What came next after the master’s?

NYSC in 2012. I served at a state housing corporation that paid me ₦2k/month in addition to my ₦19,800 NYSC stipend. I also got a few tracing gigs. At this point, I’d grown beyond charging ₦1k/sheet. I charged for the whole design, usually keeping my rates between ₦20k and ₦50k.

I got a job with an architectural firm as soon as I finished NYSC in 2013. My pay was ₦30k/month. Imagine ₦30k as a master’s degree holder being the typical going rate in the industry. I worked there for about a year, but didn’t enjoy the environment. It was a one-man business, and the owner had a bad attitude.

After I left, I went freelance for a few months. I got a couple of design contracts, but the thing about freelancing is that sometimes you get jobs and other times you don’t. When I noticed my account kept depreciating, I returned to paid employment.

My next job paid ₦40k/month. This was in 2015, and I moved in with a friend who stayed closer to my office to cut down on transportation costs. With ₦40k, I could fend for myself, contribute to home expenses with my friend, save a little and travel for interviews.

Travel for interviews?

Yes. I didn’t live in Lagos, and most of the major architectural firms I wanted to work with were in the city. So, I consistently applied to the firms and travelled down for interviews. The transport costs gulped a lot of my savings, though. At some point, I started considering moving to Lagos so I wouldn’t have to spend so much.

I eventually landed a job in Lagos in mid-2015. It was an interior design company, and they paid me ₦50k/month to teach design and do some small designs on the side. It was a one-man business as well, so it was basically slavery. They just used me anyhow.

Skrim. How did you handle accommodation, though? You know, being in a new city

I moved in with another friend. Funny enough, this friend’s house was far from my workplace, so all my money went into transportation.

I changed jobs two more times in 2015. I was constantly looking for better opportunities, ready to move to whatever looked better. The first one was so toxic, I only spent two months there. It even almost ended in a police case because my employer refused to pay me my ₦80k salary.

The next job paid ₦114k/month, and I felt like I was finally living the life. It was big money for me. I started buying things online and managed to save up for my first apartment: a mini flat I rented at ₦350k/year. I paid ₦550k in the first year because of the agreement, agent fees and all those charges. I also started thinking of settling down, and I got married a year later.

Things were looking up

Yeah. I honestly thought I was doing great. That same 2016, I changed jobs again and moved to another architecture firm for ₦150k/month. With marriage came more responsibilities. We had a child quickly, and the bills started piling up.

I worked at that firm for over six years, and the pay increases were crawling at best. By 2022, my salary was ₦243k, and I was heavily dependent on loans to pay bills, rent, and school fees.

In all the six years I spent there, I never envisaged that it was possible to earn more or do better. I thought my career was permanently tied to architecture or real estate firms.

Then, towards the end of 2022, my life changed.

Tell me about it

So, I registered for a job fair on LinkedIn by chance, and they sent job openings to my inbox. One of them was a bank that needed architects for some development they were doing in the Rest of Africa.

I applied, and after a few weeks, they called and said they thought I was better suited for a project manager role. I didn’t even know what project managers in banks did, so I started researching. I spoke to project managers and took crash courses on YouTube.

In summary, I attended the interview and landed the job. That’s how my salary jumped to ₦605k in one job change.

Whoosh. How did that feel?

I mean, it was great. I didn’t know people could earn that much. That said, I mostly felt regret. I’d wasted so many years chasing passion in architecture, completely oblivious to the fact that there were better-paying opportunities out there.

I still work at the bank today, and in just three years, my salary has jumped to ₦1.3m because of a few salary reviews and one promotion — just three years. And I spent six years in one firm. I’ll be 40 in a few months, and I honestly don’t think I can forgive myself for not doing better with my finances and career sooner.

I could’ve saved myself the trouble of debt and squeezing myself here and there to provide a good life for my family.

I mean, things have changed now

Yeah. God has been good, and I acknowledge that. Besides my salary, I still get architectural design gigs on the side to supplement my income. I don’t have a fixed rate for these gigs; I just charge as I feel, based on the scope of work and what I think the client can afford. The last client paid me ₦1.5m. Another client can come, and I’ll charge them ₦6m.

I typically make between ₦500k and ₦1.2m extra from these gigs monthly. This figure can get up to ₦5m in a really good month. Yes, I’m happier and much more financially comfortable. At least, I’m not living off loans anymore.

Still, it could’ve been better, and I think the self-pressure is because of my age. In 10 years, I’ll be 50. There’s still a whole lot to do. My children need to go to university, and I need to plan for that. When I should’ve been using my younger years to chase money, I was doing passion.

Phew. How has your income growth impacted how you think about money?

It has shown me what is possible regarding income potential, especially when you work for people who appreciate your skills and experience.

More money has also helped me see life differently. When I earned ₦243k, I couldn’t even think of savings or investments. My only thoughts were how to survive and ensure my family didn’t starve. Now, it’s possible to plan my finances ahead. I also save and invest.

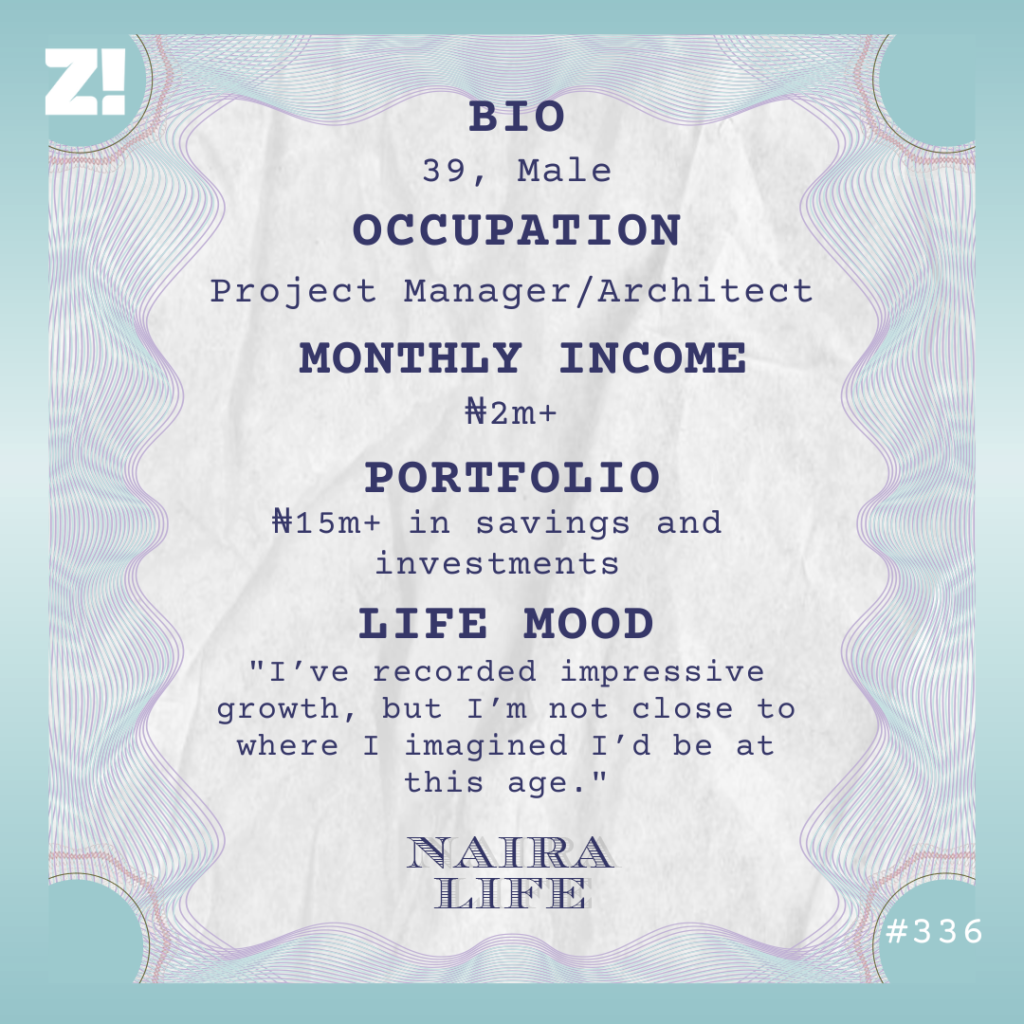

What do your savings and investments look like?

I apply the 50-30-20 rule: 50% to our needs, 30% for savings and investments, and the remaining 20% to flex and enjoy life. We don’t always spend 50% every month, and the balance sometimes goes back to savings. I also mostly save and invest whatever I make from my side gigs.

My savings and investment portfolio is spread out across different channels: ₦5.6m in treasury bills, ₦4m in a fixed deposit, ₦2.5m in money markets, ₦1.2m in bank shares, and $2k worth of S&P 500 shares. The bank shares should’ve doubled because I bought them at ₦26/share, and they’re almost ₦50/share now. It’s safe to say my total portfolio is over ₦15m.

I also have some plots of land that I bought for ₦9.5m a few years ago. Those are for my children when they need them in the future.

How about black tax commitments?

Thankfully, my younger siblings are all settled and doing extremely well in their respective fields. They even have more money than I do. I don’t think they’ve asked me for money since we left university. The most I pay in black tax is to show appreciation to my parents. I pay my mum a monthly allowance, and that’s minus other random gifts and purchases.

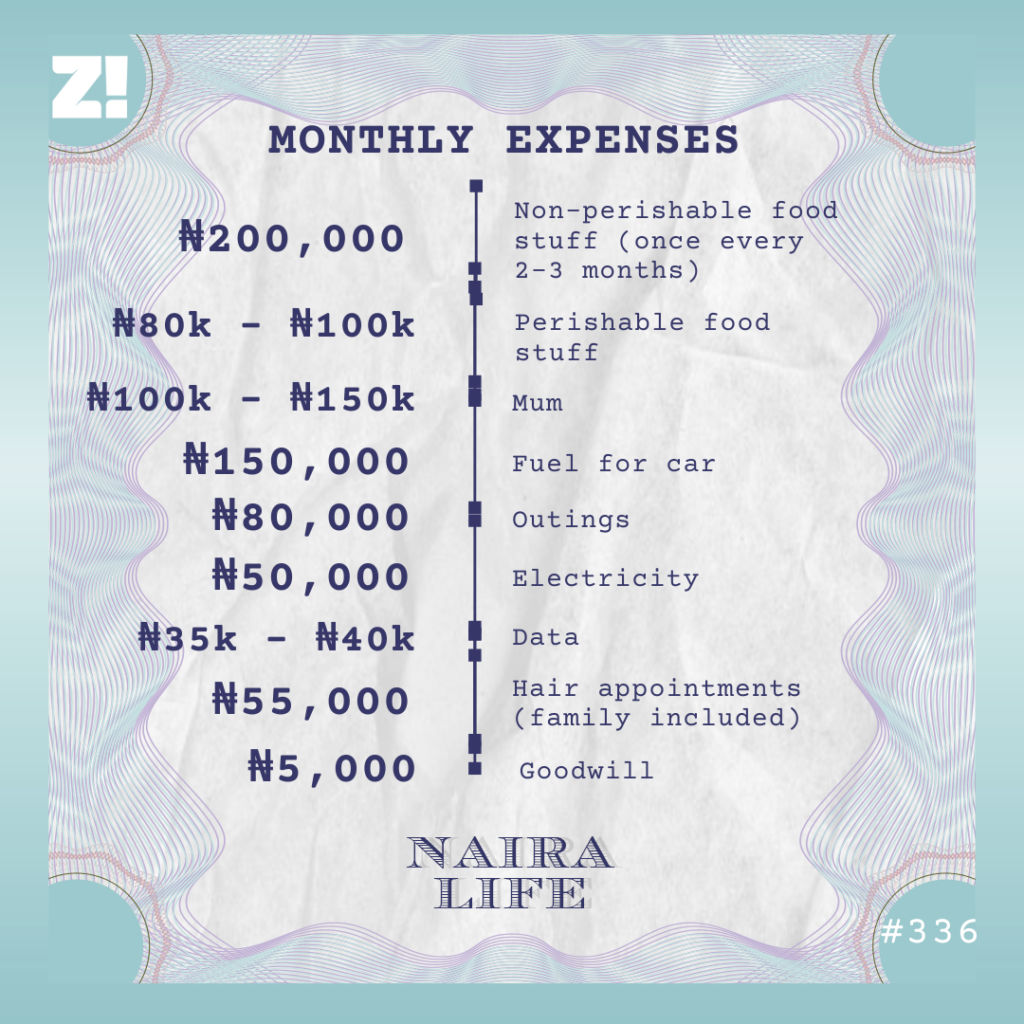

Let’s break down your typical monthly expenses

These expenses come out of the 50% my wife and I already apportioned to spending needs:

This doesn’t include my wife’s and children’s expenses (I have three kids now) because they’re in a class of their own. I call them my employers; my job is to go out, work and bring money for them. My salary goes into my wife’s account, and she manages the money. So, she takes what she needs and just gives me money for fuel and my haircuts.

The only income I manage is the one that comes from my side gigs, and that’s because I mostly channel the income to investments. Let my family hold my salary while I use this one to secure our future.

Is there a figure you’ll reach that’ll make you go, “Yes, we’re secured now”?

I’d feel secure if I had an investment that guaranteed me ₦5m to ₦7m in returns yearly. At least, that would mean I’d have roughly ₦550k to spend monthly, and I think that’s reasonable.

My family could live on that, and I wouldn’t constantly worry about bills. It’d give me the freedom to retire from paid employment and focus on my architectural design business or just explore other ideas.

Of course, to get that kind of return, I would have already invested hundreds of millions. I never reach that level yet.

Based on your current trajectory, how long do you estimate it might take you to get there?

All things being equal, 10-15 years. It’ll take a lot of effort and grit, but again, I can get there in months with God’s favour. One thing about Nigeria is that you can go to bed broke and wake up a millionaire. This country has multiple opportunities; it’s just our leaders messing it up. I mean, see how God changed my story in such a short time. I can just get one mad contract tomorrow and make all those millions I mentioned earlier.

On the career side, though, I’m targeting oil and gas and telecoms companies to probably increase my salary to ₦3m/month. On paper, I have 25 more years to work before Nigeria says I have to retire. But to be honest, I’m already tired of the 9-to-5 life. I won’t last that long.

How would you describe your relationship with money?

I‘m always very scared to spend money. I’ve had too many experiences with being broke. In fact, my heart starts to beat fast if my account gets a little low because anything can happen. My car can cough now, and the mechanic will say I should bring ₦500k.

So, I’m very conscious about how I spend. I want to give my family a good life, so I can’t afford to live lavishly. We have reasonable fun, but nothing too extreme. The only thing I think about is how to multiply my money legally.

Is there anything you want right now but can’t afford?

I’d like to change my car. Let me even buy something for myself that looks expensive. But what I want will cost at least ₦40m. Do you know what it means to spend ₦40m on a car and be entering potholes? AH. I can’t do that.

Unless I have like ₦300m in my account, I can’t bring out ₦40m to buy a car. Even if someone gave me the money, I’d first think of investing it rather than buying a car.

What was the last thing you bought that made you happy?

An Alienware laptop for my designs. It makes my job very easy and lets me put a premium on the service I render to clients. I got the laptop for ₦6.5m last year.

The price almost made me cry, but I was happy too. I’d tried to save up to buy it years before, but the naira devaluation kept increasing the price. I couldn’t buy it at ₦1.2m, but look at me now, I was able to buy it at ₦6.5m.

Love to see it. How would you rate your financial happiness on a scale of 1-10?

7.5. My journey hasn’t been easy, but I picked up lessons along the way. I’m also glad I’ve been able to make my finances work since the turnaround in 2022. I’m seeing my money grow, and it’s a great feeling.

There’s always room for improvement, though. I’ve recorded impressive growth, but I’m not close to where I imagined I’d be at this age.

If you’re interested in talking about your Naira Life story, this is a good place to start.

Find all the past Naira Life stories here.