Shalewa Oyegoke (35) has been through 15 surgeries, years of chronic pain, steroid-induced complications, and countless dismissals by doctors who didn’t believe her or refused to listen.

What started as a simple ovarian cyst diagnosis in 2014 turned into a decade-long battle with her body and a healthcare system that failed her at every turn. In this piece, she shares the story in her own words.

Trigger Warning: This story contains descriptions of medical negligence, gaslighting, chronic illness, mental health struggles, suicidal ideation, and body trauma.

This is Shalewa’s story as told to Princess

In 2014, I got into Law School. In less than three months, I lost the love of my life: my dad. That year was already brutal, but then came the pain in my belly. I kept thinking it would pass, but then I fainted in class a few times. The eventual scans showed an ovarian cyst. I thought I could manage it until school break, but it got worse, and I was rushed to Aminu Kano Teaching Hospital.

It was hellish. The hospital staff ignored my friends and me. One healthcare worker muttered in Hausa that she couldn’t be bothered with girls who probably had a botched abortion. I begged them to do a pregnancy test, anything, just to help me. It wasn’t until around 5 a.m. that a doctor, likely heading to or from prayers, asked what was wrong. I showed him my scans and tests. He asked a nurse why I hadn’t gotten a scan at the hospital; she said the radiology department was on strike. He wheeled me to maternity and did the ultrasound himself.

The cyst was much larger than earlier scans showed. It could rupture at any time. I was terrified, but I consented to surgery. My Law School friends were incredible through it all. I got discharged early so I wouldn’t miss our mandatory dinner.

That was the first time I felt truly dismissed in a medical setting, but it wouldn’t be the last.

Between 2014 and 2019, I had multiple surgeries for ovarian cysts, adhesions, and intestinal obstructions. It was exhausting, traumatic, and expensive.

And doctors kept dismissing me. One said I should just get pregnant in case that would help “expand my insides” or as insurance, in case I couldn’t get pregnant later. I still don’t know if that was because of my health or because he thought no one would want to be with me. It was astonishing and almost creepy because I was crying in pain, and he just reiterated, “I’d advise you to get pregnant now oh!” Another called it a spiritual attack and suggested I go to my village.

The cruelest part? With every new surgery, the pain-free window got shorter. After the 2015 surgery, I felt okay for nearly a year. But by 2018, I needed two surgeries in the same year.

In early 2019, I lost my stepmother, the woman I was living with and caring for. After my last abdominal surgery in March in Jos, one of my best friends encouraged me to seek new medical opinions and move to Lagos. There was a job opportunity tied to a company my half-brother had set up, so I made the move.

The pain came back, but I refused to go through surgery again. One day, I passed out in Ojodu. A friend recommended a nearby hospital. The doctor agreed that another surgery would be a bad idea. That alone made me feel safe.

He tried conservative management for the pain and obstruction for some time. Then he suggested a corticosteroid injection — Kenalog 40 — to reduce inflammation and hopefully stop the obstructions. Normally, I would webMD everything, but my big mistake was that I did no research. I had gotten a Kenalog injection once for a keloid in my ear that reduced it a bit, so the doctor saying that it would reduce inflammation made sense.

NEXT READ: The Hospital Told Me to Wait Until I Had Another Baby Before They’d Give Me Birth Control

The injections started in March 2021.

By April, my birthday month, I noticed I was gaining weight. By May, things spiraled. Deep, purple stretch marks carved into my skin: arms, breasts, belly, thighs. My face swelled so much that smiling or talking hurt. My skin bruised if anyone so much as held me. I couldn’t sleep. My moods became erratic. I was awful to the friend who was my caregiver, then I’d cry, apologise, and repeat the cycle. My belly swelled. My weight shot up from 82kg to over 130kg by the time I stopped the shots in September.

When I finally confronted the doctor with my concerns, stretch marks, swelling, and bruising, he laughed. Then, he turned to my male friend instead of speaking directly to me. That wasn’t new; he often ignored me during visits, once even saying, “Let’s talk man to man, you know how these women can be.”

That day, when I was crying about my body and terrified about what was happening, he said to my friend, “Talk to her. Does she want to be alive, or does she want to be fine? What are stretch marks? I’ll give her cream and it’ll disappear in two weeks.”

I was stunned. Then I started crying.

According to him, the symptoms were “normal.” But nothing about what was happening to me felt normal.

The side effects were devastating.

- Moon face

- Brittle bones

- Migraines

- Hypertension

- Seizures

- Hair loss

- Periods stopped

- Stretch marks

- Tooth chipping

- Nail breakage

- Skin thinning

- Cushing’s Syndrome

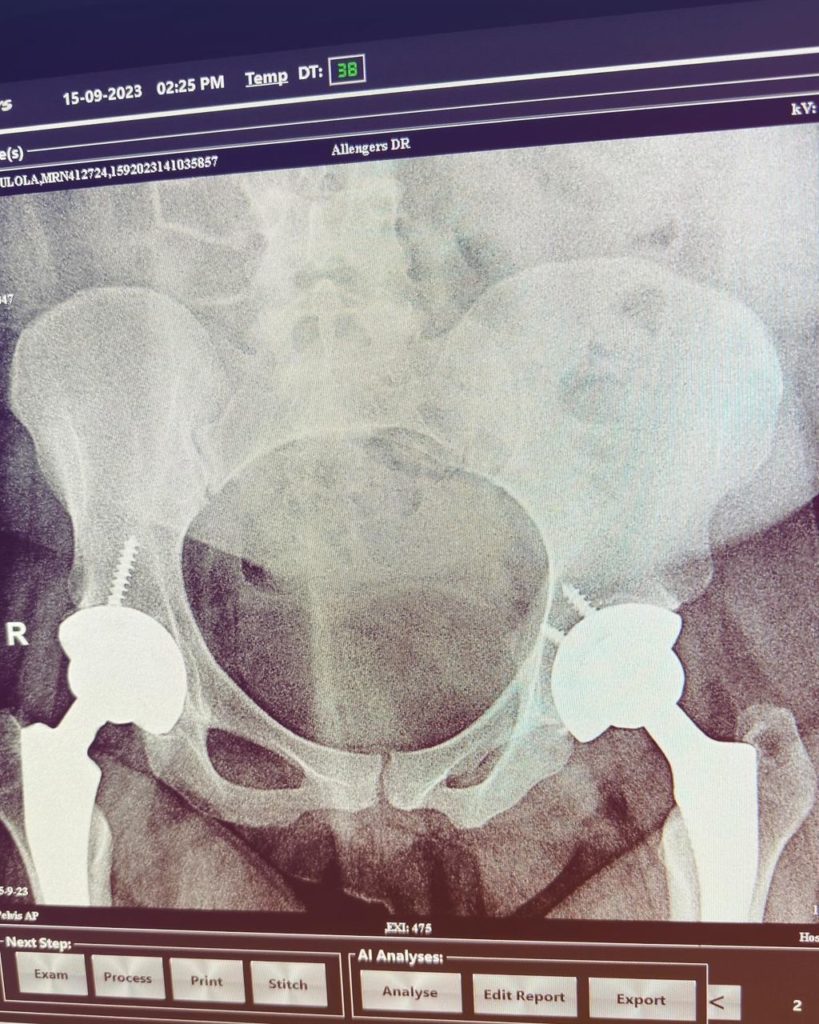

- Avascular necrosis in both hips

- Osteoarthritis

- Pre-diabetes

- Hypothyroidism

- Insomnia

- Memory loss

- “Roid rage”

Eventually, I got gluteal abscesses from the injections and couldn’t walk. Another surgery revealed I had AVN — Avascular Necrosis. I needed a double hip replacement and couldn’t afford it, so I turned to crowdfunding.

That period was hell. I couldn’t look at myself in the mirror, so I had to resign. Dependent completely on my friends and some family, I felt like a burden. I attempted to take my life four times, but my friends refused to let me go.

I’ve done three public fundraisers: for my bilateral hip replacements, my shoulder surgery last year, and my knees this year. Crowdfunding brought out the best in people, but it also exposed me to cruelty. Some family members said I was disgracing the family name. I couldn’t walk, but they were worried about their reputation.

Romantic relationships? Out of the question. Who would date me?

READ THIS: I Was Almost Forced to Marry My Cousin at 11

Now, it’s surgery number 15. I’ve stopped counting the minor ones. I’m trying to lose weight, just to feel like myself again. I’ve worked two or three jobs through all of this. I don’t just want to survive, I want to thrive.

And yet, I know this story isn’t unique. I hesitated to speak out for so long because I didn’t want to be seen as a victim. But if this could happen to someone educated, vocal, trained in law, someone who knows how to speak up, what about the women who don’t even know they’re allowed to?

There’s no doubt in my mind that being a woman shaped the way I was treated. I was often dismissed, mocked, or told I was being “emotional.” Once, a nurse advised me to trap a man with pregnancy before I “scared people off” with all my medical issues. When the signs of Cushing’s Syndrome became obvious, the doctor acted like I was just vain.

But I’ve also had good doctors. Dr. Laketu diagnosed my AVN at a general hospital. He took his time. He listened. Then there’s Dr. Osawe, who handled my hip surgeries and referred me to every specialist I needed: an endocrinologist, neurologist, psychiatrist, and physiotherapist. He’s made me feel human again. I’ve also met incredible nurses who helped me hold on.

I’ve considered litigation, but I’m still dealing with the physical fallout in 2025. I plan to report him to the Medical and Dental Council. I heard, though unconfirmed, that his hospital was shut down or his license was suspended. But it wasn’t for what he did to me.

So what does justice look like?

For me, it’s naming the problem. It’s making sure people know this happened. That this keeps happening. Because the Nigerian healthcare system isn’t just broken, it’s dangerous. We are told not to question doctors. We are taught to endure pain silently. Especially as women.

If I could say one thing to Nigerian doctors, it would be this: Listen. Listen without judgment. Without bias. Don’t assume you know more about someone’s pain than they do. Women know their bodies. We may not have the medical vocabulary, but we know when something is wrong.

To any woman going through this, afraid to speak: You’re not alone. You don’t have to be ready to share. But please know this doesn’t define you. You are more than a victim. There’s strength in speaking out, and there’s power in naming what hurt you.

We deserve to be believed. We deserve to heal.

READ NEXT: What She Said: She Gave Me the Child I Couldn’t Carry