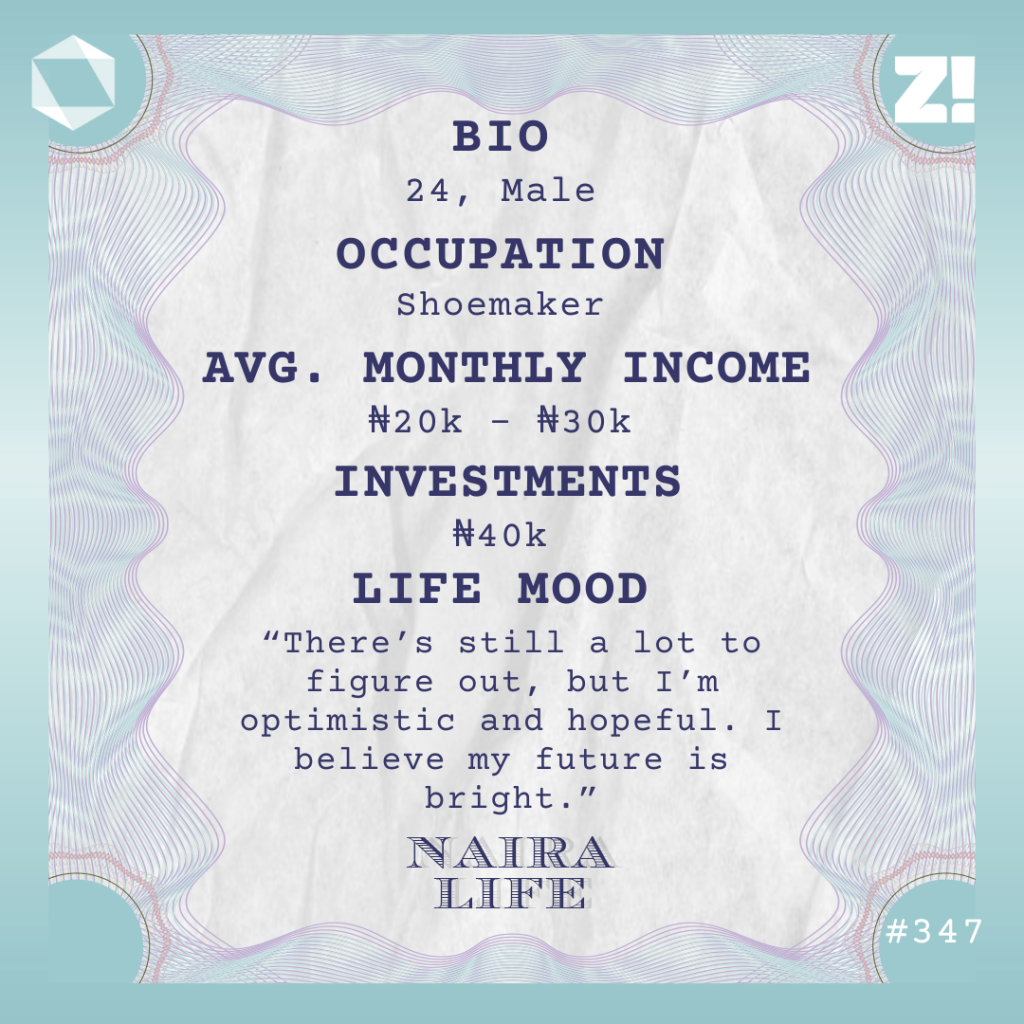

Every week, Zikoko seeks to understand how people move the Naira in and out of their lives. Some stories will be struggle-ish, others will be bougie. All the time, it’ll be revealing.

Over 5 million people trust Carbon to reach their goals without drowning in debt. Transparent terms, fast approval, and full control. Turns out, loans don’t have to come with pain. Click here to start.

What’s your earliest memory of money?

My aunt, whose place I used to wait at after school until my parents returned from work, usually gave my siblings and me ₦5 or ₦10 to buy sweets. Sometimes, we would take the money home and give it to our mum to keep. Of course, we never got the money back.

Of course. What was the financial situation at home like?

My parents were civil servants, and growing up was pretty chill. We weren’t “rich”, but I never worried about what my next meal would be. I don’t think I lacked anything, really.

Do you remember the first time you earned money?

That was in uni. I made money writing assignments for some of my guys. I started it when I first got into uni in 2017, but I was a naive young boy. They’d ask for my help, and I’d do the assignments for free; I only asked for money for printouts.

However, in 300 level, I realised they were taking me for granted and I needed to start charging for my time. So, I began demanding small payments, usually ₦2k – ₦3k.

How often did these assignment requests come?

Not frequently. In a semester, I could do about six assignments. My earnings from that supplemented my ₦10k – ₦25k/month pocket money, so I lived a relatively okay life as a student. At least, I didn’t go hungry even though I rarely cooked.

Besides the assignments, I also had a couple of volunteering stints with an NGO, where I got a ₦2k stipend whenever we went out for campaigns. It wasn’t an actual income.

Fast forward to 2022, I graduated from uni, then I taught at a secondary school for NYSC the following year. My only income was the ₦33k allawee, which I supplemented with money I made from shoemaking.

I need to give you some context for this shoemaking part.

Haha. Yes. When did you learn shoemaking?

2022. The long ASUU strike came just before my final exams, and I was idle and frustrated at home. I wanted to learn a skill that wasn’t already saturated. I’d already learnt graphic design earlier, but I wasn’t getting any gigs. I didn’t want to be a fashion designer because that’s what all my siblings learnt, and it felt like I knew too many tailors.

One day, I just thought, “What of shoemaking?” I didn’t know many people who did that, and I felt that footwear was something everyone bought, whether they had money or not. In fact, at the time, my footwear was the most expensive thing I owned. That’s how I came to a decision: I would learn shoemaking.

My parents were against it, though. They wanted me to continue in graphic design. Some of my friends didn’t like the idea either, mostly because of the “prestige”.

They said, “How can you be a graduate making shoes?”

But I didn’t care. We’re talking about money here, and you’re saying graduate. Is it better to be a poor graduate?

Plus, the person I planned to learn from was also a graduate. So, that was extra motivation. I was just like, “Fuck it. This is what I’m going to do.”

Energy. Did you have to pay to learn?

Yes. I paid ₦30k. The training was supposed to last a year, but I ended up learning for about four months because ASUU called off the strike, and I had to return to school.

However, from the first day of my training, I was already telling people I made footwear. I didn’t know how to do shit, but I was posting, “I’m a shoemaker” on my WhatsApp status.

My boss was a very nice woman. Whenever I received orders, I would tell her, and we would make the footwear together. It made me learn faster, while earning small cash on the side. I made like ₦1k profit on a ₦5k pair of palm slippers.

I moved to a different state for NYSC in 2023 and didn’t have any way to continue learning. I didn’t even have a machine to work with, so I initially planned to act as a middleman for footwear orders. I’d take orders, look for a shoemaker to make them and charge a little profit. But after making a few findings, I realised the arrangement would make the shoes unaffordable for people.

Instead, I decided to talk to the shoemakers and asked them to allow me to work from their shops. Luckily, I found someone who allowed me to do that. He didn’t charge me, but I took the initiative to occasionally buy him bread and drinks, or give his apprentice small money whenever I worked at his shop.

What was your income flow like?

It was pretty good. I stayed in a corper’s lodge, and sometimes I took the shoes I worked on home to complete them. When people saw me, they’d ask what I was doing, and I used that to spread the word. So, I was getting clients from my WhatsApp status and through word-of-mouth referrals.

In a month, I was sure of making at least five footwear. Some people also came to me for shoe repairs. My price for new footwear depended on the design. My customers were fellow corps members, and I couldn’t charge much. Plus, the number of shoes I made was more important to me than putting huge price margins on only one pair.

My only strategy was to add a ₦1200 profit to the cost of materials and transport for whatever footwear I was making. Then, there was a popular restaurant in my area that sold a plate of food for ₦1200. My reasoning was, “If I work, I’ll sha chop.”

Real. Did you do this throughout your service year?

Yes, I did. After I finished NYSC in 2024, I returned to the state where my uni is located, with a plan to double down on shoemaking. I was convinced I could make more money by putting more energy into my craft.

My theory worked. I stayed among students and quickly started getting customers. Unfortunately, my parents pressured me to return home to Lagos after three months. I got to Lagos and everything just dried up.

Phew. You stopped getting customers?

Not totally, but there was a big difference. During NYSC and in school, I had a community of people I could talk to and plug my work. But Lagos is like a jungle; no one sends you like that.

I decided to use the opportunity to improve my shoemaking skills. I found a shoemaker and paid ₦40k to learn more designs. I even paid the ₦40k in instalments.

How long was the training for?

I only spent about three months there because I secured an internship through a government-funded graduate internship scheme, which places people in various organisations. My internship was with an insurance company, and they paid me ₦60k/month for the three-month period.

While doing that, I returned to school for my master’s program because my parents wanted me to. They weren’t even in support of my learning more shoemaking skills. They insisted on the master’s until I relented. I’m still on it. I’ve completed my coursework, though; only my project is left.

How do you support yourself in school?

It’s mostly my parents. They don’t give me an allowance, but I tell them what I need for school, and they pay for it.

When I’m not in school, I live at home with them, so I don’t have major expenses. I handle petty expenses with the income from the occasional shoemaking orders. I usually pile up the orders for when I return home during the weekends so I can work on them at my boss’s shop.

On a positive note, I now have a filing machine, but that’s just one of the many pieces of equipment I’ll need if I hope to stand on my own one day.

What’s your income like these days?

I make an average revenue of ₦100k/ month, but my profit after deducting the cost of materials and transport only amounts to between ₦20k and ₦30k. It’s not big money, but at all at all na im bad.

At least, I’ve gone from charging ₦5k to at least ₦15k, and I market my business on my various social media platforms. I know I can earn more from this if I put in more effort and acquire additional equipment. I’m also jobhunting, but nothing has come out of that yet, so I’ll have to hold on to shoemaking.

If I push harder, I might even make more than whatever a 9-to-5 job would give me. I’m open to every opportunity.

You mentioned equipment. Have you thought about what you’d need?

The last time I wrote down a list of machines, it totalled about ₦10 million. But that’s on a full industrial scale. For a start, I estimate about ₦500k for equipment. The most important things I need are shoe lasts and a sewing machine. That ₦500k doesn’t include the cost of renting a shop. I don’t know how much that would be.

How would you describe your relationship with money?

I’m stingy with money like mad because I don’t know where the next one will come from. If I don’t need something, I won’t buy it. My major expenses are data and small stocks that I buy once in a while.

Stocks? How did you start?

I started in 2020 with a fintech app that allows you to buy shares from global companies like Apple, Microsoft and Google. I didn’t know much about it; I just put money there that time. I can’t even remember how much. Then, when I was broke, I took it out.

It wasn’t until recently, when I started seeing buzz around foreign stocks, that I realised I could’ve made so much money if I hadn’t sold it. The incident drove me to research financial instruments and education. Now, I try to put small ₦1k here and there in stocks. I follow people who talk about money online and try to observe what they’re doing.

I currently have like ₦40k spread across both Nigerian and US stocks. The dividends aren’t much because it’s still small money, but I figure it’ll grow as I stay consistent with it through the years.

Do you also save, or are stocks your primary financial instrument?

I don’t typically save. I used to buy dollars to keep my money before, but I stopped because the naira started gaining against the dollar, and it no longer seemed profitable to buy dollar. I should also have some Bitcoin somewhere, but it’s been a while.

Let’s break down your typical monthly expenses

Is there an ideal amount you think you should be earning?

If I see ₦500k/month right now, whether from a 9-to-5 job or my business, I’ll be chilled.

What do future plans look like for you right now?

Honestly, I’m still figuring it out. I want to do more with shoemaking; I also want to get a good job. I’ve been searching for one within the advocacy sector, but I’m fine with anything. There’s still a lot to figure out, but I’m optimistic and hopeful. I believe my future is bright.

Rooting for you. Is there anything you want right now but can’t afford?

I’d like to change my phone to an iPhone 11 Pro Max. I don’t even know how much they sell it. Maybe ₦400k?

How would you rate your financial happiness on a scale of 1-10?

Happiness? Zero, abeg. I’m not happy at all. I have no cash. That’s not a happy situation.

Hoping things change for the better soon. What would make you happy?

Thank you. If I see 100 orders now, I’m sure that rating will change. I believe it’ll happen one day.

If you’re interested in talking about your Naira Life story, this is a good place to start.

Find all the past Naira Life stories here.

[ad]