Every week, Zikoko seeks to understand how people move the Naira in and out of their lives. Some stories will be struggle-ish, others will be bougie. All the time, it’ll be revealing.

When did you first realise the importance of money?

When I was about 7 or 8 years old, I visited my older married sister, who lived in a different city. Her house had toilets and running water. Until then, I’d spent my whole life in a riverine hamlet in Bayelsa State where everyone fetched water and eased themselves in a public place.

I cried when I returned home after the holiday at my sister’s. I knew my real life was far from what I’d experienced, and money was the difference.

What was money like at home?

There wasn’t any. My father was a fisherman with two wives and many children, while my mum dried and sold the fish. One day, just before I started primary school, my father left us to fend for ourselves.

I spent most of primary school living with one family member or another to ease my mum’s load. The family members weren’t always nice to me, though. One time, I needed ₦600 to register for my first school leaving examination, and my uncle claimed he didn’t have money.

I knew he did; he just didn’t want to give it to me. He also had a habit of berating me when he was angry and telling me it was my fault my dad left.

The heck?

My headmaster finally paid the ₦600, and I wrote the exam. This was in 2005.

In the same year, the military burnt down our village. They came because some bad boys in the community caused a riot. The soldiers were supposed to “make peace”, but they killed multiple people. Subsequently, my family split up for a year.

My mum fled to a different village, while I, along with my dad’s first wife and her children, went to another town, where we lived as refugees. I couldn’t attend school, so I hawked pepper soup and plantain to survive. When we eventually returned to our village, I lived with yet another family member to continue my secondary school.

In secondary school, I had the opportunity to earn money for myself. Actually, my desire to earn money came out of need. I needed things like school snacks, socks, and sandals, and I couldn’t ask relatives for everything.

So, what did you do?

In SS 1, I started practising how to make hair with young children and friends. After a while, people started paying me. One woman paid me ₦300 every time I did her daughter’s hair. I also wrote classmates’ notes for ₦300 – ₦500.

At the same time, I helped manage my aunt’s bar and cold room. In the mornings, I hawked frozen chicken before school. In the afternoons, I hawked chicken legs cooked in stew. In the evenings, I helped out at her bar.

Sounds like a lot of work

It was. My responsibilities at my aunt’s businesses only increased when I finished secondary school in 2010. I wanted to further my education, but my aunt didn’t want to let me go; I was the only one who stayed with her despite her hot temper.

That woman could beat someone till they fainted and continue till they woke up. She had three girls, but none wanted to stay back to help with the business. Instead, I did all the work while she used the money to train her children.

I understood she didn’t have to sponsor me — I wasn’t her child, after all — and it only made me determined to find my way. I wanted something better for my life.

If I stayed, I’d probably get pregnant by some boy, and then my life would be over. So, six months after secondary school, I escaped to my mother’s village.

What did you do there?

The plan was to contact my dad’s brother to sponsor me to computer school. For context, my dad died in 2006, and even though we hadn’t seen him for years, I attended the burial with my mum and siblings. There, my uncle offered to take responsibility for my brothers, most likely out of a guilty conscience.

When I returned home, I called my uncle, who agreed to pay for the computer training and asked me to come to his place in Port Harcourt. The only problem was that I didn’t have transport fare.

My elder sister was at home, so I did her hair and asked her to walk around the community. I was hoping people would like the hair and ask for her hairdresser. That’s exactly what happened.

Some people in the community were planning a burial at the time. In my place, burials are like Christmas. Relatives and friends come from different cities, and the people in the village always want to look presentable for the “visitors.”

For the next two weeks, I had customers who paid between ₦500 and ₦700 to do their hair. That’s how I gathered money to move to Port Harcourt. I enrolled in a six-month computer training course, but I worked at the computer centre for four extra months.

What was the pay like?

₦5k. All I did was type and do other secretarial duties. But I trekked to work and only ate at home to save my salary. I didn’t even use the savings for myself; a friend needed help to buy JAMB form, and I loaned her ₦15k. She never paid me back.

In 2012, I went to live with my sister in Yenagoa and found another job at a computer centre for ₦8k/month. I did that for three months, then a church member gave me a passport printer and camera, which I started using to take people’s passport pictures for a fee. I’d stand in front of the university to hustle for customers.

One day, I ran into one of my aunt’s customers from the bar. He said he heard I had learnt to use a computer and was looking for a secretary for a short-term contract. I said I could do the job, so he tested my computer skills and gave me the job. It paid ₦60k/month.

Whoosh. How did that feel?

I was excited. It was the highest I’d earned until that point. The man also gave me ₦10k for transport, and I immediately entered the market to buy a basin of garri, rice, and beans. I took it home to my sister, who didn’t understand where I saw money. I just explained I’d found a job.

I worked there for six months and pursued higher education during this time. I constantly listened to the radio because schools advertised admission exams. As they announced them, I registered and wrote them all.

I was admitted to a nursing school sometime in 2012, but my ₦100k savings weren’t enough to cover the tuition, which was ₦180k. My family also couldn’t raise the balance, so I had to let go of the admission.

That same year, I heard a radio announcement about a NIMASA scholarship to study marine engineering and nautical science. The announcement said interested applicants could pick up forms from a place I no longer remember. Interestingly, I heard the announcement on a Friday, and the exam was the next day. I picked up the form, wrote the exam, and got a notification five days later that I had passed the first stage.

What was the second stage?

Travelling to Lagos for a medical examination and verbal interview. Thankfully, the government sponsored my transportation and accommodation.

After the second stage, everyone returned home to wait to see their name on the acceptance list. I waited for two years before my name finally came out in 2014.

Did you hold out hope during those two years?

Yeah. I heard it could take a really long time to get an answer, so I just kept hoping. While I waited, I took different school exams but didn’t have the money to move forward with my applications.

At a point, I just decided it was better to wait for the scholarship. In the meantime, I tried my hands at several trades: catering, bead-making, improved my hairdressing skills, etc.

My decision to wait paid off in the end. The scholarship clicked, and I went off to the Philippines.

Oh. The school wasn’t in Nigeria?

It wasn’t. The federal government had an arrangement with the school, so scholarship awardees didn’t need to pay for tuition, accommodation and feeding. However, the feeding part wasn’t great. I think our government told them we were less privileged people, so the Filipinos treated us as such. They gave us spoilt, uneatable food, and it was a whole thing.

Anyway, my course was marine engineering. It meant I needed to complete three years of coursework, return to Nigeria for a compulsory one-year at sea, then return to the Philippines to finish my program, get cleared and collect my certificate.

During the first three years, the federal government paid me a ₱5000 monthly stipend as part of the scholarship. I also made money in school by making people’s hair. I made so much money that I briefly considered leaving the program and making hair for a living.

How much were you making from hair?

I charged each client between ₱1000 and ₱1500. At the time, one peso was ₦7, so this was approximately ₦70k. I had three to four clients every week, and I also did occasional home service. Home service fetched me as much as ₱18k. In a typical week, I made between ₱5k and ₱10k.

Most of my earnings went into black tax — I learned that term from other Naira Life stories — and savings. By the time I finished my three-year study in 2017, I’d saved ₱30k. I gave it to a friend to hold while I returned to Nigeria to find a ship for the one-year compulsory experience.

The government wasn’t going to sponsor my return to the Philippines for my certificate, so that ₱30k was my safety net.

How did the search for a ship go?

It was messy. Several students before me were still waiting for ship placements due to the limited options. I couldn’t wait for the government to help, so when I landed in Nigeria in 2018, I moved around from place to place, dropping my CV everywhere.

Fortunately, I got a role on a ship within weeks as an engine cadet —a trainee role. However, the pay was just ₦10k/month, and I still had to feed myself. Other ships paid between ₦60k and ₦100k for that position, but I stuck with what I found. I needed the experience more than the money.

I can imagine. Did you return to the Philippines after completing the one-year experience?

Yes, I returned in 2019. My friend used the ₱30k I’d saved with him to cover my flight and accommodation costs. I should mention that I got married while in Nigeria. By the time I returned to the Philippines, I was six months pregnant and couldn’t do some of the physical training required to complete my clearance.

So, I did the theoretical aspect and waited until the following year, when I finally got my license. During that time, I resumed my hairdressing hustle. I returned to Nigeria in January 2021.

I’m curious. Did you consider staying back?

I wanted to, but the Philippines’ immigration system isn’t favourable. They didn’t have a permanent residency route, and I could only stay if I kept studying. Plus, they didn’t like giving jobs to foreigners. My husband wouldn’t have anything to do if he came to join me. So, I just came back to Nigeria.

My child was about a year old, so I went for NYSC to give the child some time to adjust before looking for work on a ship. Four months after I completed the service year, I found a job aboard a ship.

What was the job?

I was a second engineer, maintaining the engine room and machinery. My work schedule was one month on and one month off the ship. My salary was ₦546k in the months I worked on the ship and around ₦250k when I was home. This was in 2022.

In 2023, a friend helped me get another job with a German company. My salary was €2600/month — about ₦2.6m at the time — and I had to board a ship from Italy or Spain, which meant a lot of travel.

That’s a massive jump from ₦546k

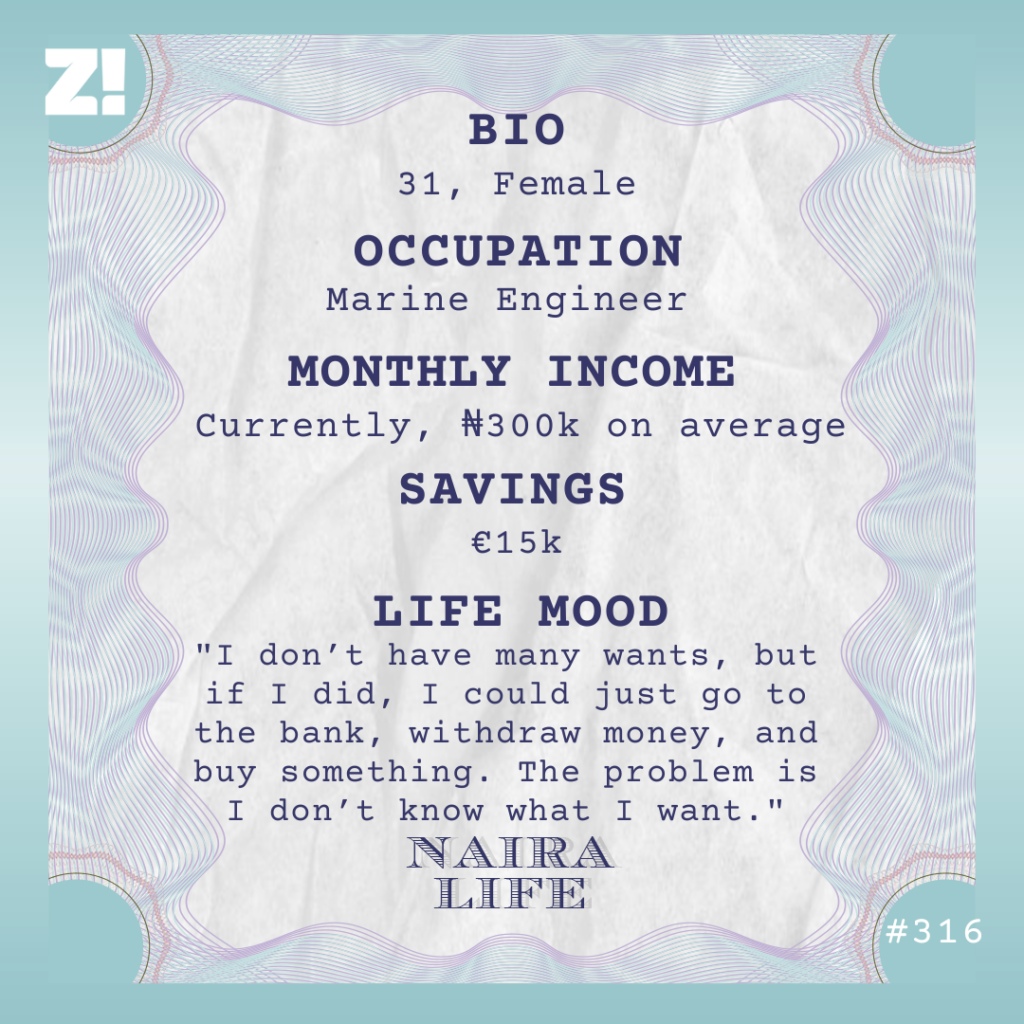

It was. Funny enough, I wasn’t moved. I struggle with knowing what to do with money. I don’t buy expensive clothes, and I don’t even wear wigs. I’m more likely to give my family and friends money than spend it on myself.

Plus, my husband isn’t doing too well financially, so I’m responsible for the family. I guess I saw more money as, “Yeah, this is good, but more money means more responsibilities.” So, I didn’t fixate on the income growth.

I worked on the ship for a year and transferred to an office role assisting the technical superintendent in 2024. I was five months pregnant and couldn’t stay on board for my safety. The office role allowed me to work from home, but my salary was slashed to €1k — about ₦1.6m. I worked in the role until last month, when my contract ended.

Oh. What are you doing these days?

I have a store where I sell dry fish. I opened the store last year when I got pregnant because I knew I wouldn’t be aboard a ship anytime soon. I just wanted somewhere I could go and be around people. Whenever I had to be at work, I just closed the shop.

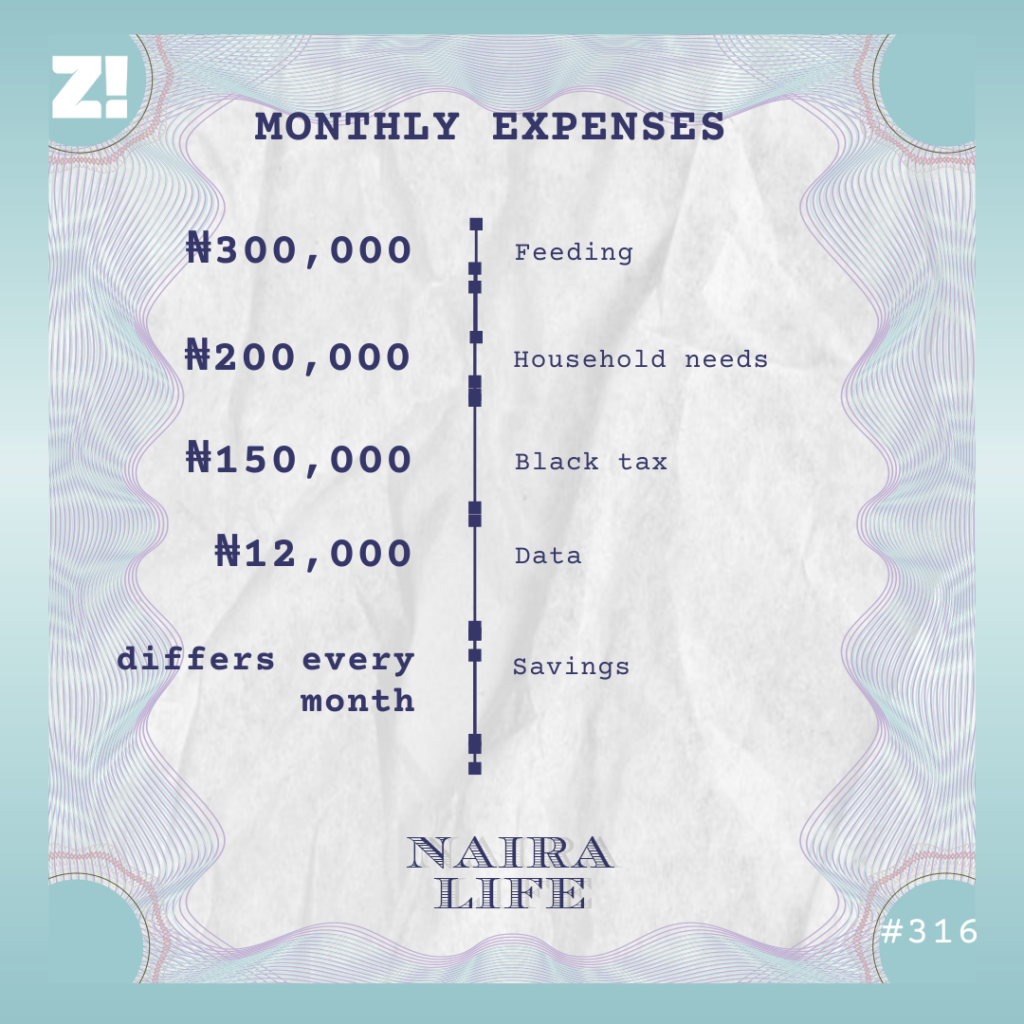

It’s not a serious income source like that. I have someone who sends me fish once a week, and I sell them both wholesale and retail. I often make at least ₦50k in profit weekly and ₦200k – 300k monthly.

I’m supposed to return to work in a few weeks, but I don’t know if that’ll happen because I’ve still not gotten a visa. Typically, the visa comes out in three weeks, but it’s been two months, and I’ve not heard anything. Hopefully, it will come out soon.

Fingers crossed. How would you describe your relationship with money?

I have a constant need to save for long-term survival, and I attribute that to my background. I don’t buy things for myself. You could tell me a pair of shoes costs ₦20k, and I’d be rationalising why I absolutely don’t need them.

If I give someone else that ₦20k, they’d appreciate it more than whatever I need the shoe for. My husband does most of the buying — clothes for me and the kids and other household needs — because left to me, I wouldn’t buy anything. I just don’t want to be stranded.

If something ever happens that I can’t work for a year, my family should be able to live on what I’ve saved. I’m lucky I got transferred to office work and still had an income during pregnancy. Still, I have to be prepared for eventualities.

I admit I overdo the not wanting to spend on things, though. I find it difficult to buy anything for myself, but it’s probably a side effect of my line of work. Who cares that I’m wearing ₦60k shoes on a ship? Or that I wear a wig? I don’t go to events when I’m home because I’m usually too tired. So, it’d be useless for me to gather expensive things. But I still want to learn to care for myself and spend more.

You mentioned savings. What does your portfolio look like?

I have €15k in my euro account and one ₦200k in a Nigerian account, which I currently don’t have access to because the bank people want me to come and update something.

My husband and I plan to use the €15k to build a house because our house rent is killing us. Our landlord recently increased our rent from ₦500k to ₦700k, and it’s not sustainable. We have land and estimate we’ll need at least ₦10m to build a three-bedroom apartment.

At least ₦10m should make the building livable enough to move into, and we can finish up other things as they come.

Could you break down your typical month in expenses?

We buy our food in bulk, and the budget is high because two relatives also stay with us. My black tax budget spreads across my mum and the different family members I grew up with. They weren’t always nice to me, but I feel they impacted my growth in some way, so I have a responsibility to them.

Is there anything you want right now but can’t afford?

Nothing. I don’t have many wants, but if I did, I could just go to the bank, withdraw money, and buy something. The problem is I don’t know what I want.

What was the last thing you bought that made you happy?

My plots of land. I have four in total: two in my and my husband’s name and another two in my name. I got the first two in 2022 and 2023 for ₦800k and ₦1.1m respectively. The last two plots cost ₦2m in 2024, and I got them because I wanted to have property in my name. I feel like there’s almost nothing as motivating as seeing a woman working hard and owning big things.

Inject it. How would you rate your financial happiness on a scale of 1-10?

8. I don’t want much, so I’m pretty satisfied. My main focus now is finding balance. I want to build safety nets and assets for me and my children’s future.

I also want to learn how to relax and get good things for myself with the money I’m making. Let me not just stress about gathering money and not getting to enjoy it before I leave the world.

Zikoko readers are currently giving feedback about us this year. Join your voice to theirs by taking this 10-minute survey.

If you’re interested in talking about your Naira Life story, this is a good place to start.

Find all the past Naira Life stories here.

Join 1,000+ Nigerians, finance experts and industry leaders at The Naira Life Conference by Zikoko for a day of real, raw conversations about money and financial freedom. Click here to buy a ticket and secure your spot at the money event of the year, where you’ll get the practical tools to 10x your income, network with the biggest players in your industry, and level up in your career and business.

[ad]