For someone who likes history a lot, I don’t like Slave Islands or Doors of No Return. I still haven’t been to Badagry. Ouidah only has the arch, and stories scattered across the Internet. Kunta Kinteh Island was outrageously expensive.

But Goree Island, Senegal’s own ‘Slave Island’, seemed inevitable.

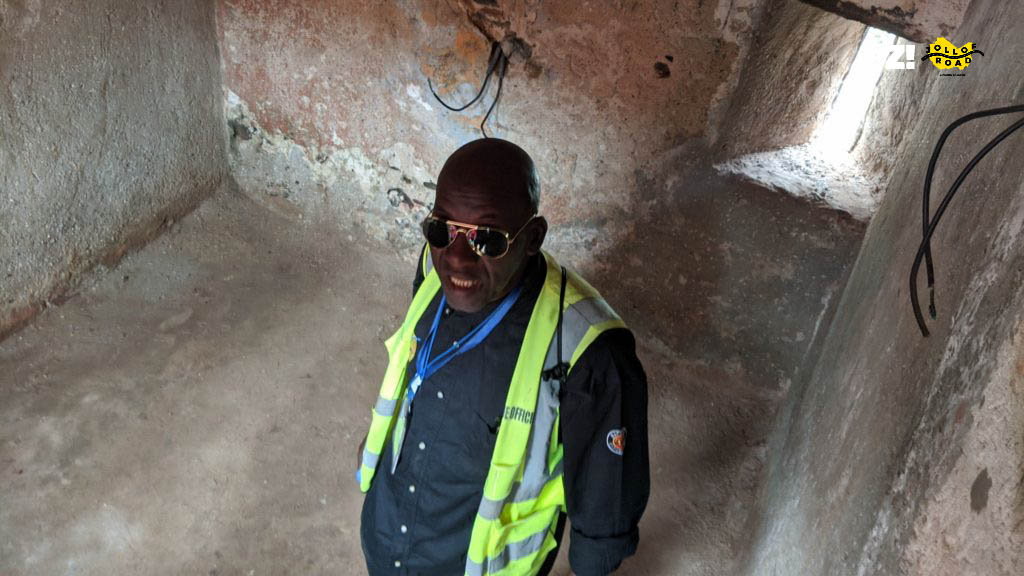

“Ah, you’re Nigerian,” one man said to me, with his dark shades. His name is Isa. “You have Badagry and Calabar, we have Goree Island.”

“My name is Fu’ad.”

“Nice to meet you, Fu’ad,” we shook hands, and then he just goes on to drop more facts. “You know, most of the people they carried were either Yoruba from Nigeria and Benin, or Igbo, or Bambara from Mali, or Wollof from here.”

“When you get to the Island, you’ll need a guide,” he said just as we were going to get our tickets, “let me know. I’ll wait for you.”

The boat that carries people from the Dakar port to Goree Island has a 300-people capacity. It costs 5,000 CFA for non-Africans, 2,700 for non-Senegalese Africans, and 1,000 for Senegalese. The trip takes 20 minutes.

I don’t know if visiting Goree Island when we did was a good idea, but as the Island came in view, I felt a growing dread for the place.

I’m currently listening to a podcast by the New York Times; it’s called 1619. That’s the year the first 20 slaves reached America. 20, not because that’s all the slave traders enslaved from Africa, but 20 because those were the only ones that made it to America alive.

Goree Island is the farthest point of no return. At 3.5km off Africa’s most westernmost Mainland city, Dakar (Cape Verde is the most westernmost country), it is the true finality. A certainty that, if you made it across past this island, you were going to die aboard a slave ship, and then thrown into the Ocean. If you didn’t die, the next time you set foot on land, it’d be on one where you’d be a slave.

The 20-minute ride to Goree Island ended at the Island’s only port, with its small beach. The first sound you hear is rhythmic rattling.

They call is Kes Kes here, and it’s a Percussion instrument that feels like two mini tambourines attached by a cord.

Standing in front of us waiting, was Isa.

The tour started with a quick walkthrough Goree. There’s some Dutch, Portuguese, and French history here. We walked past the Museum that didn’t open till 2.30 pm. We walked the aisles on the Island, past an art market that has all kinds of art that we’ve seen in art markets in at least 3 other countries. Past people selling fruits. Till we got to a hill on the Island, with a giant canon sitting on top.

“The French brought this here bit by bit during the World War,” Isa said, “they didn’t want to take any chance against the Nazis.”

The French mostly occupied Goree until Senegal’s independence in 1960. “After that time, many people moved from the Mainland to come and live here.”

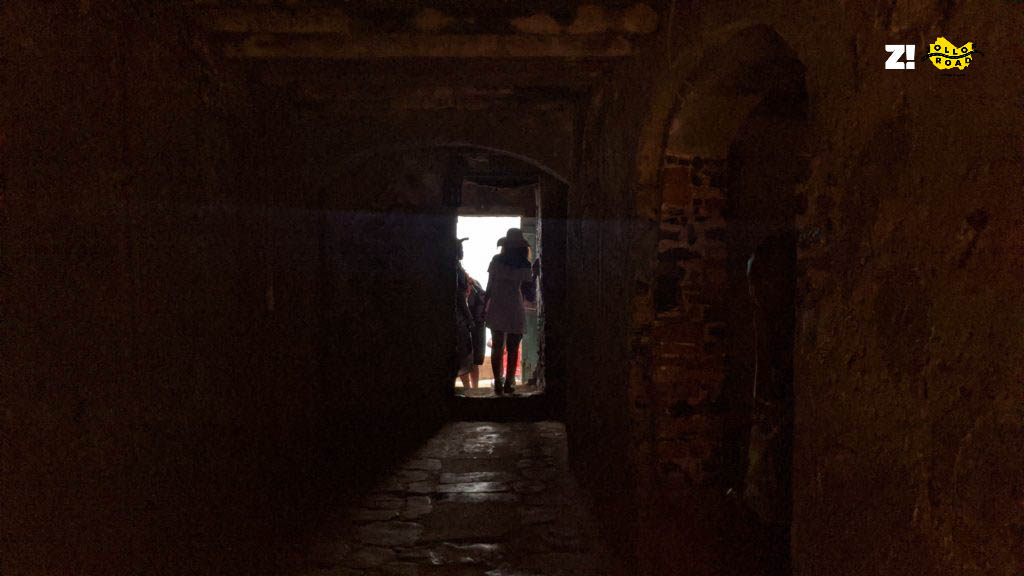

We headed to the museum. It was open now. This museum has no artefacts and well-treated photos. It’s cells. Empty cells where slaves once occupied. One cell is for children. One for men. “This one,” Isa said, “is for twenty men.” 20 men would have to be standing side by side for it to fit.

There’s a cell that’s about as high as my waist, “that one is for slaves who show resistance.”

There’s a tiny door, beyond it is the ocean. “Everyone stands here in a single file, facing the water,” Isa explained like he’d explained to every tourist for the past twenty-something years.

“Someone then comes from behind and brands them. Because their names don’t matter, only who owns them.”

A white woman was crying nearby, and Toke wondered why. There were a lot of white people there, in fact. Still, Toke wondered why they were there, taking touristy pictures.

I dunno why. I guess people deserve to know. I haven’t thought about it deeply enough to have a fully formed.

“I can’t stay here,” Kayode said, taking a few steps back towards the entrance. We followed him quietly.

By now, everyone was hungry, so we headed out to grab lunch. Then to the tiny beach for a swim.

Now, I wonder who swam at that beach and who was thrown in to die. Back when I was standing beside the water, all I wanted was a good swim in really cold water.

Previous post

Previous post Next post

Next post