Let me start by saying this is the 50th episode of the Naira Life series. If you’ve stuck around, thank you. If you’re just joining the party, welcome, and thank you.

Every week, Zikoko seeks to understand how people move the Naira in and out of their lives. Some stories will be struggle-ish, others will be bougie. All the time, it’ll be revealing.

What was it like making money for the first time in the 80s?

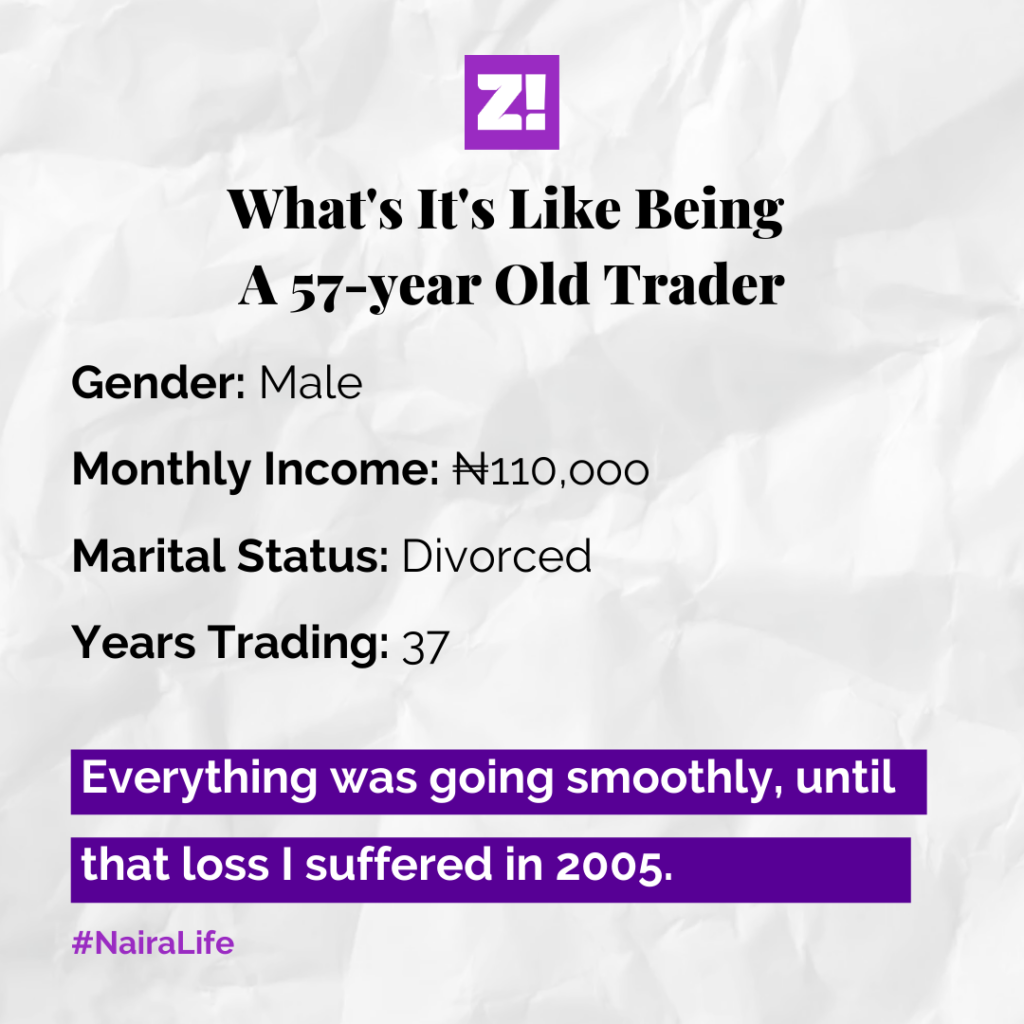

I don’t remember much, but I remember that I started in 1982.

I was living with an aunt then, and I was applying to an aeronautical school in America. I remember very well that the first payment was supposed to be $5,600.

I told my aunt and her husband about it.

What did they say?

They said that they’d have paid my school fees, but they didn’t want me to turn out like one of my uncles who travelled to the U.S. and came back addicted to cocaine.

I said, “mama I’m going to behave myself.” She said, “never. The one I sent before you, I now regret it.”

That’s the last time we talked about it. I was about 19 going on 20.

Argh.

Anyway, I finished my certificate exams and joined the family business that year – a stockfish retail business.

What was doing business in the 80s like?

Ah, I remember that a sack of stockfish cost about ₦360 in 1982. It seemed smooth, there was a steady demand at the beginning of the 80s. Some days, I’d have arrived at the shop before everyone one, and by the time they arrived, I’d have sold ₦3-4k worth of stockfish.

The business was a lot of the usual; good seasons and bad seasons, as with most lines of business. But there was always enough money to meet everyone’s needs.

But everything changed in 1986.

What happened?

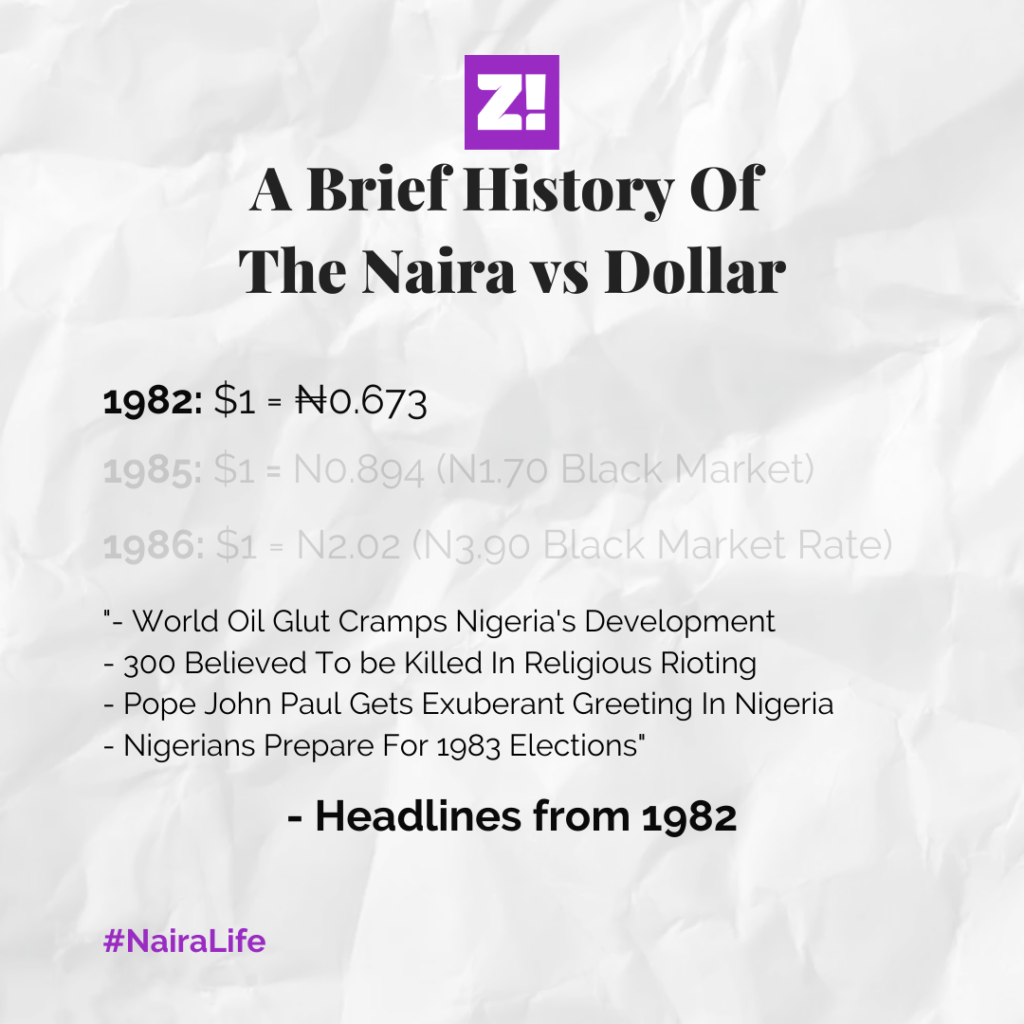

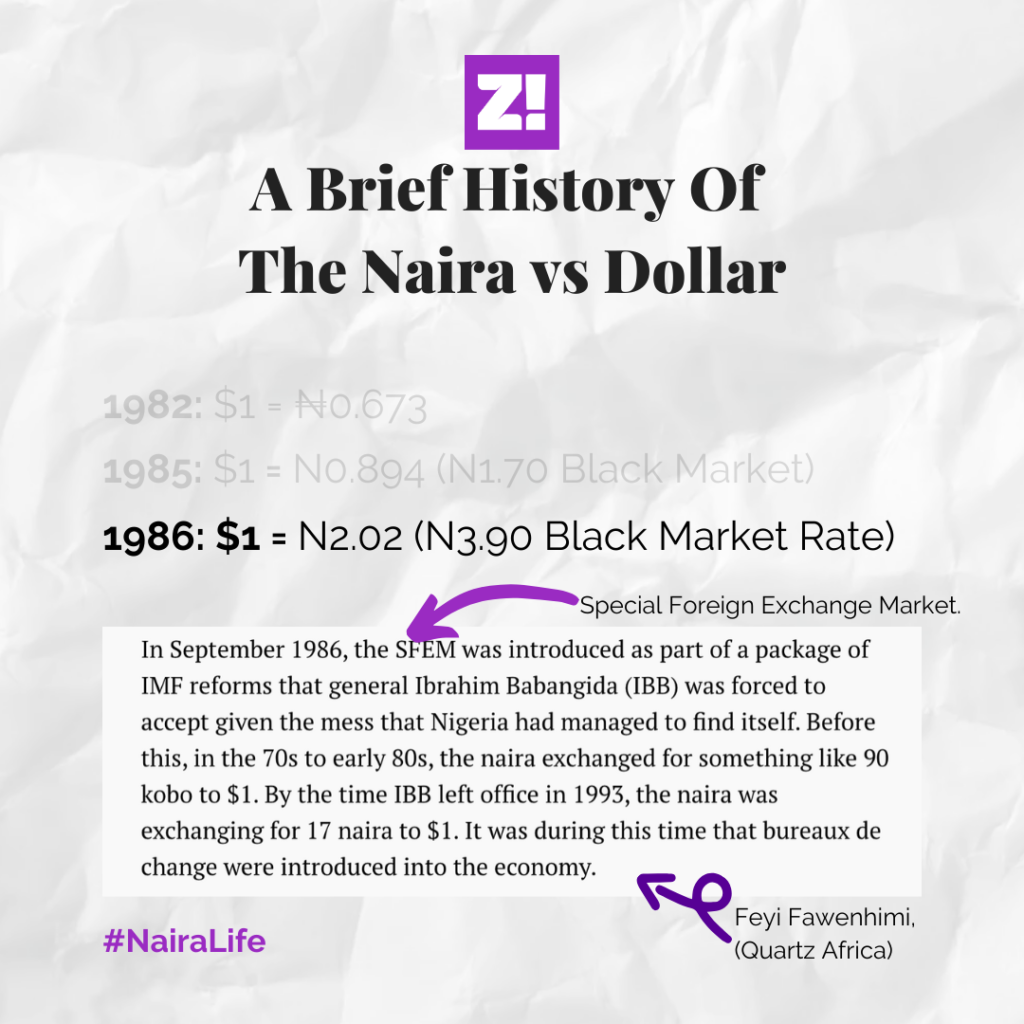

Babangida introduced something and the naira just kept falling. Something SFEM.

Let me explain what I mean. When I travelled to London in 1985 to buy things, I left on Thursday and came back on Saturday and I –

Wait, you went and spent only one day?

Ah ahn? Yes now. It used to be a visa on arrival, all I had to do was show them my cash. Sha, I travelled with £3,000 in cash, and then I exchanged it at ₦5 to the pound. My return ticket was ₦570, paid airport tax of ₦20. We – one of my big sisters and I – actually travelled to go buy clothes to come back and sell. We flew in an Airbus plane.

You know, in those days, I wasn’t even rich. But I was comfortable.

What did you spend money on in those days?

Faaji. Buying clothes and shoes. Beer. Smoke. Those days, we’d hop from party to party. Just enjoyment.

I don’t really remember a lot of the 80s again. But I didn’t have a fixed income as a trader, so I can’t say this is what I earned here or there. I just know it was enough to be comfortable.

You can’t remember anything else?

Oh wait, I got a one-room apartment in Lagos Island in 1985, around Idumota. Those days, Lagos Island was more expensive than Surulere. My room cost ₦3,600 per year. I remember that I bought a used AC at ₦1,300. I was just enjoying myself.

What else do I remember? Soup!

What happened to soup?

If you want to cook rugged soup, you’ll do it with ₦80. If you want to load it with all kinds of assorted and enjoy yourself, ₦300. If you buy pepper of up to ₦5, it means you’re trying to kill yourself.

Also, I remember another thing. I had a bank account. In those days, the bank van would come into the market, park their red and green trucks, and lower their staircases. So you’d walk into the back of the truck, and save whatever you wanted to save.

One day, the truck didn’t show up again.

Why?

They’d packed up and gone with all our money – I had like ₦13k there. But I didn’t really feel it. I didn’t have too many responsibilities.

When did responsibilities start?

The 90s – I got married. The thing about marriage is that you’ll just start having sense out of nowhere. Wake-up call.

See that wedding? I think it cost less than ₦100k in total. I remember buying ₦16k worth of drinks, from soft drinks to beer. We had a leftover of seven crates, even though my boys drank till the next morning.

Wow.

Yes o! We moved to the government flats built by Jakande once I got married, and the rent was ₦7,200 a year for a three-bedroom apartment.

My wife started in the Civil Service in 1991 and her first salary was ₦750. I was making sales of up to ₦600 per day.

Wait, by ₦600, you mean revenue?

Yes. I had only one bank account, so all the money went there. When I had personal needs, I just took from it. Then I pulled everything out when I wanted to restock.

As the years went by, the money was no longer like in the 80s, but it never really finished. I always had cash.

Do you want to know the most important decision we made in the 90s?

Please tell me, sir.

We bought a house. Lagos State Government built flats and was selling them. I think each flat cost ₦353k in 1994/5 if you were paying at once. But we did a mortgage and completed the payments in 1997 at ₦600k.

I remember the money that we used to pay the balance. Someone helped me to secure a contract to supply stationery and an oil company. The contract was valued at ₦75k, and it cost me ₦16k to execute. It was that profit that we used to pay for the balance of the house, my wife and I. A few years later, work started on phase two. The flats were a little smaller, but it cost ₦999,999. Tinubu was already governor at the time.

Why was buying that house so important to you?

Ah, if we didn’t buy that house, I would have gone back to my village. Because the coming years tested us. The houses in this estate now sell for up to 10 million per flat. This one’s on the outskirts of Lagos.

What do you mean by ‘tested us’?

In 2005, I lost a lot of money. Someone I regularly sold to, took goods on credit. It wasn’t the first time that had happened, so there was no need to worry.

This time, I never saw him again. It was most of my stock, and I ran into serious losses. There were already previous losses, but that ₦500k was like the final one I lost.

Wow.

Retail is lucrative, but it’s also high risk. That was when I took a step back from retail and switched to another line in the business. Striking, that’s what we call it.

Like, striking?

Yes, I play middleman between supplier and retailer. I help them do all the work to get goods from the supplier, and I get my commission.

Ah, like a Broker.

We call it Striker.

I wonder how this affected your relationship with your family.

I don’t do very well with asking for help, so…

So that made it very hard.

Exactly. When that tough period started, that was the period I needed my wife the most. But she just added more responsibility at work – I actually don’t blame her. Also, she had to be away, on transfer. It was just a very tough time for us.

When I think about it now, that was the beginning of the end of our marriage. What’s your next question?

Sorry, sir. Did you consider trying another line of business?

This is what I’d been doing for over 20 years of my life. I also didn’t have the luxury of going to learn something else. But the striking thing, that’s what I did.

Please explain how it works.

The supply company I work with, credit builds over time. The more you get retailers to buy, the more your credit builds. The more your credit builds, the more you can supply. For example, in 2012, I had access to ₦3 million in credit. That means that I can look for retailers willing to buy ₦3 million worth of stock and get my commission.

But the first few years were tough. I was earning about ₦50-70k per month in 2005. By 2010, I was averaging ₦120k. Then a scarcity came in 2011.

Ah.

Hahaha, it was a good thing. Because the ₦700 commission I was getting per sack climbed to ₦2,000 and by the time we moved 350 bags out of the warehouse, I made ₦700k. Neat.

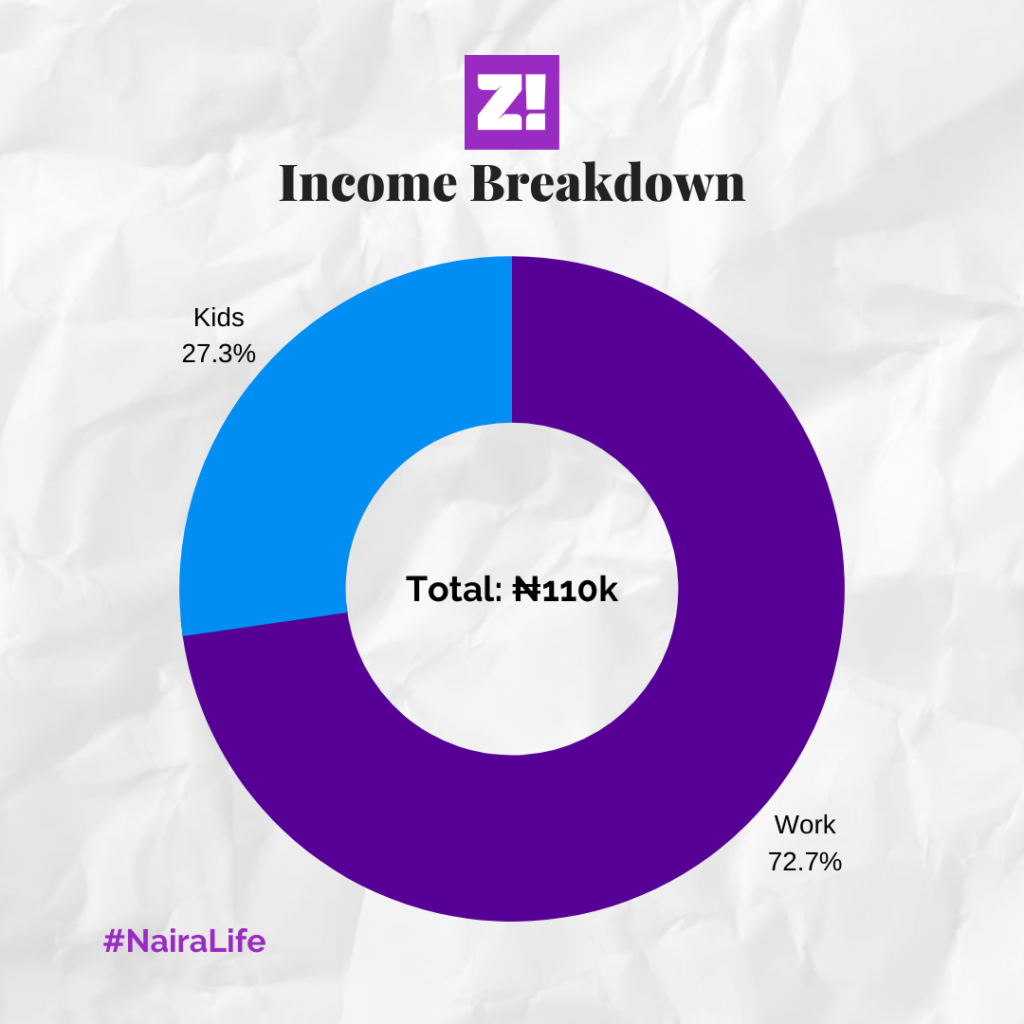

These days though, make between ₦80-100k per month on average. Then my children send me money every month.

I’m curious about how you think about money, between 1982 and now.

One thing I know has been consistent is this; things that don’t belong to me don’t entice me, including people’s money. I remember the first day I saw ₦4.7 million in my bank account in 1997. At the time the money entered my account, we were struggling with accommodation, myself and the family. The houses we paid for weren’t ready. Instead, we rented a mini-flat – a room, parlour and shared kitchen. And it is just now that you asked me that I realised that it never even crossed my mind to borrow from it.

Because it wasn’t mine.

You mentioned earning up to ₦100k per month these days. How much is really enough?

₦150k is good for comfort. I don’t go to too many parties. I just go out to work. I come back home, eat and sleep.

Talking about work, when do you think it’ll stop for you?

See ehn, I don’t think I can stop working. I believe if I stay in one place, my body will get weaker. But as long as I’m active, I feel I’m okay. I rest when I have to. I don’t know what I’ll do if I have a lot of free time.

Although, something I’m considering is looking into the car business. It’s less stress than striking. It’s not as frequent, but the margins are good.

What if you had a pension?

I’m not sure about pension o. In the 80s then, the civil servants had pensions. But there wasn’t really anything for traders. I don’t even know if I feel like I’m missing out. Someone I know retired after 35 years of service. I think he entered with a secondary school certificate, now he gets about 45k every month as pension.

That’s all I can say.

What happens if you stop working for any reason?

Wo, I’m not stopping.

Apt. How would you rate your financial happiness levels, on a scale of 1-10?

I think I’m average. Like 5 or 6. It’s not great, but it’s not bad either.

The last question, is there something you wish you could go back to change?

Go back and change? I haven’t thought about it before. What’s the point?

Note: This story was edited for clarity.

Check back every Monday at 9 am (WAT) for a peek into the Naira Life of everyday people.

But, if you want to get the next story before everyone else, with extra sauce and ‘deleted scenes’, subscribe below. It only takes a minute.

Every story in this series can be found here.