For this week’s What She Said, I spoke to Chioma, who had a life-changing experience at 19. She talks about what it felt like losing her leg to an accident at 19, how she has adapted to the change and getting a first-class in law school.

Tell me about the accident.

I remember it like it was yesterday. I was going to visit friends at Babcock, Ogun State. I had left Ajah, where my parents lived, without telling anyone where I was off to. I got there at about 2 p.m., hung with friends and was on my way back, three hours later, when the accident happened. I was heading to the taxi park, and a car hit the bike I was on. I thought, okay, I only fell down, but apparently the impact was on my foot. The car had hit my foot, then pushed us down.

Oh shit. That sounds painful. What happened after?

It was. The pain was at 120, at least. I remember being confused. There was a patrol van around, so I was rushed to Teaching Hospital, Sagamu, and they did rubbish there. What got crushed was my foot, but I wasn’t given proper primary care at the teaching hospital. They used very dirty needles and equipment. During the initial surgery to fix the foot together — because it was dangling — they used regular needle and thread, then the anaesthesia wore off, so I could feel all the pain. The next day, my dad got an ambulance to take me to Lagos, and that was when we found out an infection had set in because of the poor care.

What the hell?

Everyone thought I was going to die because the infection was spreading fast, and we had to make a decision to amputate the leg. My mum didn’t want to think about it; she was asking for other options. But the more time we spent trying to make a decision, the more the infection spread. My sister and dad decided for me. All I wanted was for the pain to stop, so I didn’t have an issue with their decision. Right now, I’m amputated from my foot to below my knee.

Oh wow. How many days after the accident did the amputation occur?

About three days after.

I know you said you just wanted the pain to stop. Once it did, how did you feel?

The first thing I felt was relief. I went through the procedure twice. For the first amputation, they took out a lower part of the leg, and I was still in pain. I was told I’d feel relief once it was done, but that didn’t happen. I was still falling in and out of consciousness.

When the doctors told me it was still infected, I wasn’t surprised. Immediately I had another amputation, to below my knee, I felt total relief. I could tell I was recovering. I stopped falling in and out of consciousness, I was responding to my drugs and treatment. I was so much better. But this was physically.

Emotionally, I had been preparing myself, but nothing prepares you, no matter how much you hype yourself. I was so afraid of my leg. When the nurses came in to dress the limb, I would avert my gaze. It was in POP, so that worked for a week. After one week, I had to stand up. When I did, I wanted to cry but couldn’t because my mum was there. I didn’t want her to cry too. I said, “Wow, this is how I look!”

It got better. I knew I had a long journey ahead of me, so I started preparing myself for that.

Tell me about the journey.

Ah. On one hand, I can say I’m doing well; on the other hand, ah. When my prosthetic leg is good, I’m living my best life given the situation, but when it is bad, even being around me is horrifying.

I’ve had to change both my leg and foot three times. I don’t have a car, but I am very active. I walk all over the place. When it’s raining, even though it’s not water-resistant, I have to put my prosthetic leg in water to go to work or church or just go out. It once broke in the first term of law school and I went back to my crutches.

When it’s bad, it’s really hard to use. It’s like when your phone is faulty, and you have to keep hitting the back to make it work. You can imagine how frustrating that is. When it’s bad, I have to use all of my body to lift it — It is metal. Without a car, it’s a discomforting period for me. I still have to go to work and do regular stuff. Though, If the reason is not important, I don’t go. Managing a prosthetic leg is not a pleasant experience.

I changed my foot in March, so I’ve been balling. It has a two-year warranty, and this is the first year. I’m trying to use it well, so it’ll last three years. By that time, I would have saved enough for a new one. October to March last year was not great. For me, my journey is dependent on how my foot is.

I know I’ve faced discrimination in a few places, but not work-wise. For work, I don’t really need my leg. And I’m one of the privileged disabled people because I can walk, so no one counts my disability against me.

Sometimes I use my disability as an advantage, like to jump queues or seek favours. I appreciate balance, I can do most things, but where I struggle, I like that people give me leeway. They say, “You know what, you’re disabled. You don’t need to prove yourself to anybody.” There’s a balance I’ve been able to curate with my friends and family.

I’m more independent because I live alone, which makes my parents panic from time to time like, “Oh, you’re living alone. Hope nothing will happen to you.” But that’s like 20%. They know I can take care of myself because I’ve been living alone since the amputation — I was in Abakaliki for chrissakes.

Abaka why?

I schooled in Ebonyi state, Abakaliki.

Ah. Go on.

I went back to school after the accident, but now I work and live in Lagos.

Okay. Tell me about finding balance.

When you go into uncertain situations, you can find your strengths, weaknesses, things that make you tire out and the rest. It took me about a year to figure out what I could and couldn’t do. Some days after I could stand, I tried to carry a bucket of water. Then I was like, what was I trying to do? I hadn’t even learnt to stand properly or use my crutches. I was even still in the hospital. My mum nearly lost her mind.

I had to reconfigure everything about me. I knew I couldn’t stand for long and walk as fast — I’m tall and my legs are were long, so I was a fast and impatient walker. Two months after the amputation, I noticed I felt pain in my limb when I walked really fast. So I studied and set a pace for how fast I could go and how long I could stand. At concerts, I stay close to the exit in case of a stampede — my prosthetic leg doesn’t allow me to run; it’s not that sophisticated. I can stand for about two hours, so I’d go to the concert when it’s at the hottest. My wardrobe used to consist of skinny jeans. I had to change the entire thing. Every day is a new lesson, so I’m constantly learning.

How did your parents find balance?

Ah, for them it was a terrible time. My dad is like an O.G. He doesn’t shake. When the accident occurred, I called him at work, which was in Ikeja. Imagine the distance to Shagamu. He went home to Ajah, picked my mum — against evening traffic. He sounded calm because everyone initially thought it was something POP would fix, and I would get better. My mum was saying this girl does not like to stay in one place, she’s always walking up and down. When they saw the extent of the damage, my mum broke down. My dad and elder sister were trying to save face. But I could see the fear. I felt bad because I thought if I had just stayed at home, I wouldn’t have caused them this kind of pain.

My mum was always crying. So even when I wanted to, I didn’t, or I cried quietly so I wouldn’t upset her. I could hear her crying or muttering prayers even with the drugs.

My dad ran around trying to foot the bill, while my mum was constantly with me at the hospital. Guests were not even allowed, but she told my dad to bring a chair for her and didn’t leave my side. She slept on that chair for weeks. No matter what she does to me now, I cannot be angry with her.

It was a trying time for everyone. My sister would tell me that my dad cried in the shower. He would be strong-faced at the hospital, but cried when he was taking his bath.

Did you ever consider therapy?

I refused therapy because we had already spent so much money, and I didn’t want to add to that. For the first year, everyone was careful around me. Any little thing, I’ll be applauded. But now, I’m old school. My family still ask about my leg because they know that If I were going through the worst, I wouldn’t want to stress them about it. They already spent millions. I got my last prosthetic with contributions from my friends and a little from my mum.

Now I need adult therapy because Nigeria has done me strong thing.

Same sis, same. You finished with a first-class from law school. What advice do you have for other law students who want to try for a first class?

Wahala for who no study day and night oh. I partied as much as I read, but I studied a lot. My sister, who is also a lawyer, advised me to study and also have fun. I wasn’t even aiming for a first-class; I was okay with 2:1.

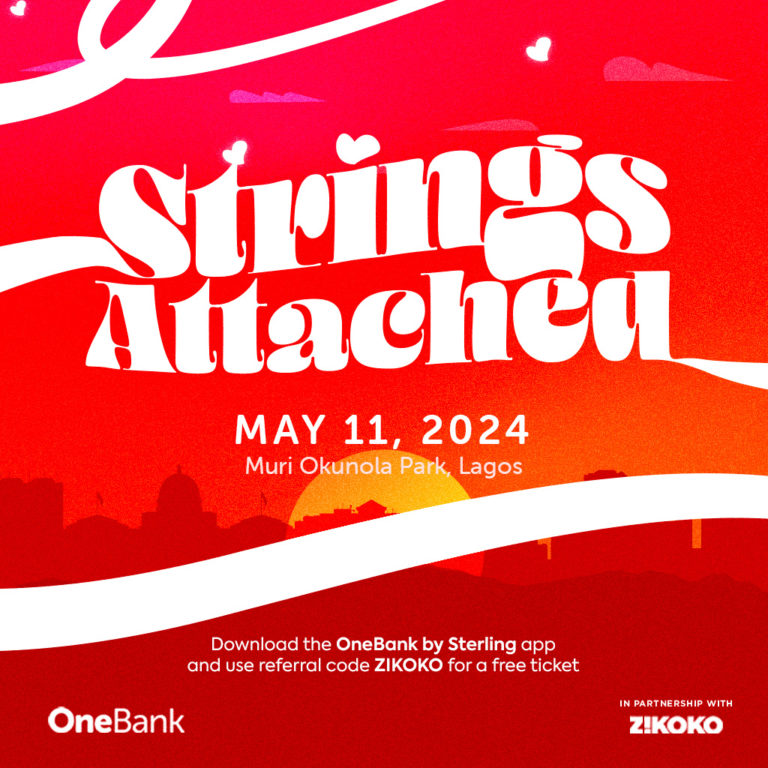

Everything about me is balance. If I decide to party at Muri Okunola tonight, I’ll study from morning to 5 p.m., then I bounce and pick it up at 3 a.m. If you don’t have balance in law school, you’ll lose your mind because it’s a very tough environment. Right now, because I found time to play, I have memories from law school. Just try to strike a balance.

Read Next: What She Said: I Was ‘Married’ To A Police Officer For 7 Years, Here’s My Story

Hi there! While you are here do you want to take a minute to sign up for HER’S weekly newsletter? There’ll be inside gist from this series and other fun stuff. It’ll only take 15 seconds. Yes I timed it.

COMPONENT NOT FOUND: donation